Derrick Adams

Be Who You Want To Be

Text by Jewels Dodson and portrait by Bryan Derballa

Do you think when Gandhi said “Be the change you want to see,” he imagined a Black artist changing the world by creating a visual landscape where Black people are anything they want to be and everything they're told they cannot be? Was Gandhi talking about Derrick Adams?

The Baltimore-born, Brooklyn-based multidisciplinary artist, with a cult following on social media, makes work found in galleries and art fairs around the world. Although he's one of today's most notable contemporary artists, the Adams I meet at his Bed-Stuy studio on a hot summer afternoon is inviting and engaging, giving off no airs of any kind. His eyes are shiny, his voice husky, and without that lush beard, his skin is like a rich ganache—brown, creamy, and glowing. Adams doesn't look a day over 36 years old but, during the course of our conversation, it becomes evident that he's earned all the wisdom of his 49 years.

I follow him into his studio, which is bursting at the seams, and there, in the middle of a white wall, is the profile of a woman composed of Adams' signature polychromatic melanated hues. Wearing a black coat stitched with a quilted lattice design, her right sleeve extends into the third dimension and makes her feel more real. This coat is exactly like the one I wore in high school; a sliver of her large hoop earring peaks out from underneath her hood. Although I have never seen this woman before, I know her very well.

The painting ignites memories of me as a sassy New York City teenager, and instantly I am filled with a warm nostalgia. The work welcomes me in, and just like that, I am seduced into Derrick Adams's world. I imagine this deep sense of familiarity is what many viewers experience looking at Adams's work. His masterful use of cultural imagery and artifacts captivates the eyes while creating a connective tissue between his work and the viewer that makes them feel right at home.

When Adams left Baltimore for New York City in 1993, he pursued a BFA at Pratt Institute and embarked on the path most students take, acquiring any number of hustles to keep their dreams and themselves alive. Adams interned at the New York City Hall Art Commission, learning how to install shows, while also working at PHAT FARM on the weekends. He says his time at PHAT FARM taught him about consumerism through fashion and urban culture, a concept that has become a recurring theme throughout his work.

Subsequently relatives, Danny and Russell Simmons opened RUSH Philanthropic Arts Foundation. RUSH opened a gallery space in Chelsea and became an early home for underrepresented artists of color like Ed Clark, Frank Bowling and Xenobia Bailey. Renee Cox who was on RUSH's board, curated one of the gallery's first shows which included Andres Serrano and Lyle Ashton Harris. Adams says, “I was privileged to be around all of these master artists in my 20s who didn't have the same experience of being internationally known as their peers who were not Black. But to us in the community, we thought of them as masters, long before the world took notice.” RUSH became a safe haven for Black artists and Adams developed long lasting bonds with New York's art community.

Adams soon became the gallery and curatorial director, and what the position lacked in salary, it made up for in invaluable education. As director, he was instrumental in helping artists construct their artist statements, assist in production, and coordinate installations. While heading up the gallery, Adams also acquired an MFA from Columbia University, taught at Medgar Evers College and Columbia University, continuously produced work, and was represented by Jack Tilton Gallery. Through this experience, he became well versed in the administrative and operational aspects of producing a show and running an art space. The acquisition of this knowledge made Adams a different kind of artist, giving him more control in the production of his work and the direction of his career.

Fellow artist, colleague, and friend of Adams for 25 years, Mickalene Thomas, recalls a young Adams with leonine locks when they met at Pratt Institute when she was a freshman and he was a junior. She recalls Adams' work at RUSH Arts Gallery as being important because, “He created a platform for so many artists for over a decade, supporting those artists and using that gallery experience to understand the art world and the art market, and having that experience as the foundation for his own career. But he shifted the paradigm and started taking care of himself a little more and nurturing himself.“

In 2009, Adams had the revelation that comes right before something important happens. Realizing, “If I can run a gallery for 13 years while making art and going to grad school, if I can do that and do it in a way that has helped other people be successful, why can't I put the same energy into myself?” He soon after resigned and became a full-time artist. From 2009 to 2012, he honed in on the concepts he wanted to explore and mediums to express those ideas. He says, “I realized once you enter the circuit of the professional space, people look to you to keep making that thing, if that thing was well received. But if you make a bunch of different things, you can have way more reach. If I'm making video, sculpture, and collage, I can have different shows based on this output while still keeping the concepts intact and based on my personal interests, expanding the outcome and the artifact of an idea.”

Adams's work started to catapult, Thomas recalls, “I think that shift happened probably about five years ago, when he started doing the collage work, but also when he started painting more. In undergrad, he mostly focused on performance art, installation, and sculpture, but I think when he started focusing mostly on two-dimensions, his work took a shift. When he started using those same concepts and theories from performative works in a more two-dimensional aspect is when that shift happened.”

2014's LIVE and IN COLOR, Adams's third solo exhibition was a tour de force. He skillfully layered and juxtaposed vibrant colors, shapes, and textures in an aesthetic that has now become a staple in his visual repertoire. While entrancing viewers, he addressed a recurring theme throughout his work: media representation. In this series, he deconstructs popular black television archetypes and stereotypes. He pushed the viewer to question their relationship with media. “I realized that there is a stigma with certain types of imposed imagery that has been placed on the black body through media and through history. We have accepted certain stigmas as kind of defining who we are,” he says. Adams sought not to deter viewers from indulging in any kind of “type” but encouraged them to divorce themselves from any attachment to a type. For people on the margins, it is even more important to detach from the hyperbolic representations of themselves in the media, perhaps minimizing some of the image's power and lessening its impact.

Our culture is knee-deep in an ocular revolution. The human brain processes images 60,000 times faster than words. 90% of information transmitted to the brain is visual. People remember 80% of what they see. 65% of people are visual learners. 95 million photos and videos are posted to Instagram every day. Adams's fascination with imagery and representation is not just about pushing against a larger structure, but a golden opportunity for him to transform antiquated narratives. “For me, as an artist, I realized that you have the power to redirect people's relationship to imagery based on inserting them into different contexts. And, in that way, if the current generation doesn't see it as being an alternative perspective, then the younger generation will start to adopt those images in a way that's totally separated from the generation before. I have the ability to change the course of the future language of visual culture. That's what artists do.”

If you search #derrickadams on Instagram there are 5000+ posts. Several of his paintings feature his signature polychrome people dressed in swimwear, enveloped in an assortment of life-size floats in the shapes of unicorns, confetti-glazed donuts, chocolate ice cream sandwiches, and pineapples. In Adams's utopian universe, the subjects leisurely bob along the Costa Rican blue pool water, without a care in the world, casually commanding, “Siri play Lil Duval's 'I'm living my best life.'”

But this wasn't always the case. A random search on IG for “floaties” in early 2015 resulted in plenty of photos, but none with black people. So Adams created the change he wanted to see and the Float series was born. At first glance, Float is like a visual pop tart—colorful, playful, and easy to digest. Black people floating in a pool may seem trivial, but Adams's work is surreptitiously subversive.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, racist tactics were implemented all throughout the United States to exclude Black Americans from public pools. If Black people entered a pool it was evacuated and drained. At times, lye was thrown in pools to deter Black swimmers, who were often asked to provide “health certificates” to prove they were disease-free. On June 11, 1964, in St. Augustine, Florida, Dr. Martin Luther King was arrested at the Monson Motor Lodge restaurant. A few days later civil rights activists conducted a wade-in at the pool of the Monson Motor Lodge to protest Dr. King's arrest and St. Augustine's overall segregationist injunctions. In an attempt to remove protestors, the motel manager began pouring muriatic acid into the pool. That moment was broadcast around the world and became a seminal reason President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Float series debuted in May 2016 in his show, Culture Club, at the nonprofit Project for Empty Space in Newark, New Jersey, where Derrick was an artist-in-residence. It is a series of large-scale mixed media painting-collages infused with vibrant African prints and graphic fabrics. For this work Adams explores concepts of celebration and leisure, giving permission to Black people to just be; to exist wholly as themselves. Adams challenges the narrative of Black people constantly being weighed down by oppression. He remixes the narrative for Black viewers to be seen and to see themselves as literally and figuratively buoyant.

“That's what I believe as a contemporary artist right now, as a Black person. I think we have very little time to be giving props and praise to problems in our art. And I think that we should be creating solution-based structures within our work that would empower people not to ignore the problem but know that we've been through a lot of stuff and we're still here, and we're still making quite an impression on the world.” Adams says in a time where publicly elected American citizens are being told to “go back to your own country,” it is revolutionary to take ownership of one's own existence. Adams's work is necessary now more than ever.

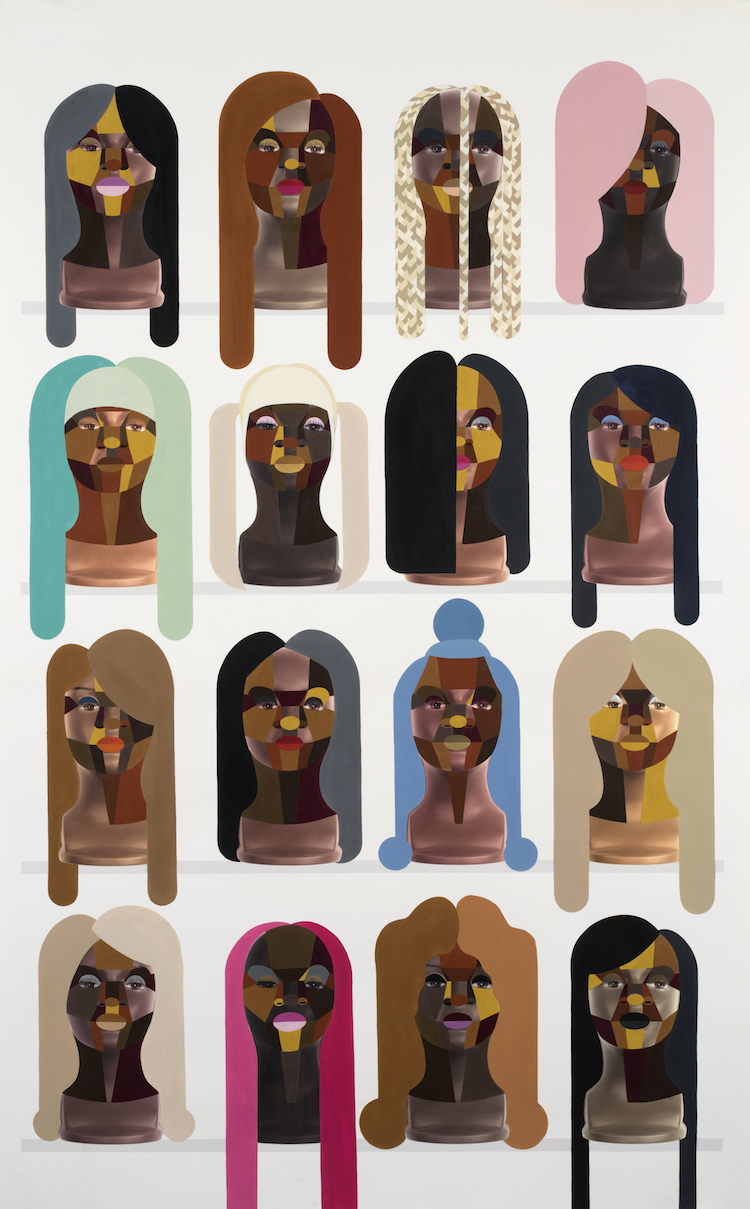

Back in his studio, pinned against the walls, there are about 12 polychrome people with varying expressions, all wearing whimsical, cone-shaped birthday party hats. This work-in-progress will be part of Adams's show at the Hudson River Museum. Adams is also preparing work on his next show Where I'm From, the first solo exhibition in his hometown, being held at The Gallery in Baltimore City Hall. This show came to fruition because Adams's sister Victoria Kennedy, a published author in her own right, was creating a collection of family photos, some that Adams found visually compelling. He began large-scale oil paintings of his family photos that capture the essence of kinship and the spirit of Baltimore.

The foundation of Adams's work is simple. He makes what he wants to see. “When I'm making my work, I'm not even thinking about my race. I am my race. I'm just thinking about what I want to make and what I want to see. I want to see a figure that's identifiably familiar to me.” In his work, he creates the kind of world he wants to live in, which is generally a space where Black people are enough. They don't need to explain themselves and they don't need to be anything other than whatever they are in that moment—they are sufficient.

Adams invites everyone to visit, and Black people are more than welcome to stay. Like so many of the greatest artists, he is untethered from white gaze and unattached to what anyone thinks of his work. Thomas said, “He's always told me to just keep making the work and not give a shit what people think. Let the work speak for itself.” Choosing to make work that is honest and beautiful, and because truth and beauty are universal concepts, people the world over connect to the work. He is playing a dynamic game of tennis with the viewers—a rich dialogue ensues.

In 2020, Adams, like his counterparts Titus Kaphar, Nick Cave, and Kehinde Wiley, will each be opening spaces to support artists in their endeavors. Adams is currently in the embryonic stages of building out a studio/incubator space in Baltimore that will consist of an artist residency to assist creatives in moving their ideas forward through mentorship and bridge-building. This is the sort of “pay it forward” that usually just brings more success.

Derrick Adams's work creates a world that celebrates joy, freedom, and unabashed Blackness. He's done what great artists do: give people respite in the midst of a storm and empower them to reimagine their own worlds.