Danielle Orchard

A Day On The Green

Interview and portrait by Sasha Bogojev

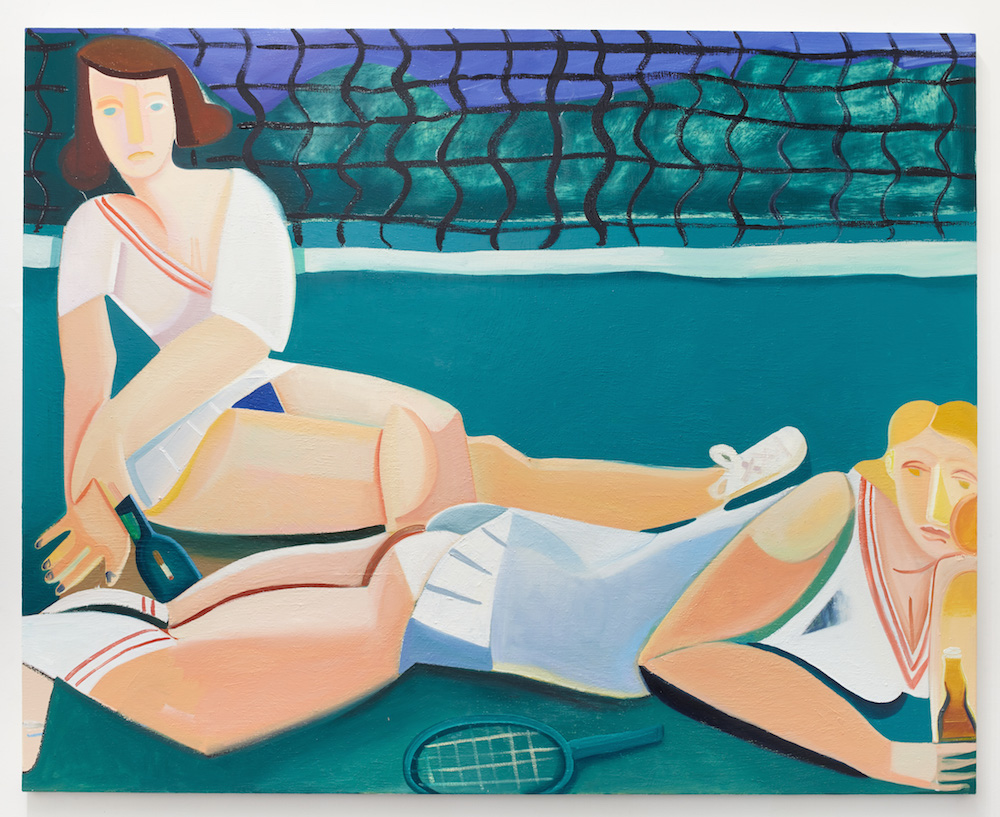

The works of Danielle Orchard, at galleries and art fairs, strike very classic poses amid much of the surrounding contemporary work. Dominated by female figures, Orchard's images conjure Picasso's muses emerging from a machine to experience life in the twenty-first century. Content with their bodies and being, the women lounge around, sharing a bottle of wine, having a cigarette, reading a book or enjoying intimate time to be themselves.

Masterfully manipulating thick layers of paint and unexpected tones, her images successfully combine the long-established painting traditions with the carefree ambience of modern-day life. Unique color choices are used to create haunting, mid-afternoon light and perspective effect through bold brush strokes and strategic painterly gestures. The results are atmospheric images that evoke languid lethargy and the buzz of cicadas in the background. Orchard's works admit human foibles and critiques in cubist packages of life and leisure.

Sasha Bogojev: I'm going to start off with an odd question—what's with the tennis references in your work?

Danielle Orchard: What's with tennis... that's a good question. These images entered my work around the time Serena Williams was in the news for refusing to wear an "appropriate" outfit during a tournament. She was rebelling against male policing of the female body, and it was really beautiful to watch. I became interested, after that, in the history of women's tennis uniforms. They have always been contingent on the broader public's relationship to female sexuality. It has little to do with the female body in motion, but 100 percent about censorship and what men deem acceptable. At one point, uniforms were ankle-length; then in the 1970s, they get really short. So it's kind of all over the place.

I was more interested in women's uniforms and the aesthetics surrounding tennis than in the activity itself. My relationship to the sport is speculative, and relates to desire and projection. Desire and coveting are present in all of my paintings. I depict things I imagine myself doing, environments I fantasize about inhabiting. But, instead, I'm just painting them.

I ask because some of the painters I'm liking, like Friedrich Kunath, Jonas Wood or Guy Yanai, they have these tennis images, as if they're tennis-obsessed too.

Right. I've been thinking about those painters, as well. But theirs seem to be much more about the geometry of tennis, which is, itself, quite beautiful.

Yeah, exactly. That green.

That green. That impenetrable, really dense tennis green, you know? It reminds me of Lacoste or something, immediately recognizable. It's symbolic, and for that reason, immediate. When I see white next to that particular green, I think of sport, and... you're just kind of plunged directly into that world. Which is really fascinating, I think. So the tennis imagery resulted from a confluence of interests. I was really into the outfits and how they're a perfect example of women's bodies being policed by men—even while we're playing sports. An athlete's body is on view, and that's ostensibly what spectatorship is about—watching a body do something amazing. Yet, still, there's someone telling women that their dresses are too long or too short or... you know, controlling the terms of female athleticism.

You clash this sporty feel of tennis playing women with women relaxing with cigarettes or booze. Was that somewhat of a rebellion?

It's rebellion, but it's also personal failure. It's about deciding to do something and then not being fully engaged. It's about ambivalence. And it also suggests a moment in time occurring either right before or right after physical activity. Sport is so much about immediacy and being in the moment, with everything happening in a second. These images pause that action, and instead, place it in Seurat's world or someplace like that, where everything is very still and fixed.

Aside from tennis outfits and the occasional socks or underpants, your subjects are usually naked. What's the idea behind that?

The nudity is meant to evoke a sense of timelessness. These figures aren't attached to any era. That freedom—or maybe suspension is a better word—relates to my interest in figurative sculpture. Typically, in, say, Italian Baroque sculpture, there might be a nod to an era in which something was made, but the female figures are typically nude. This allows them to be immortal. Of course, art historians could determine things from how the figure's hair is fixed or whatever. But to the layperson, these sculptures represent women who will never die—were never born, but will never die. Its a beautiful space to exist, I think.

What outside stimuli make you feel more creative, give you more impulse to create, and what type of things make you feel like not doing anything?

Aside from seeing art, I don't really know. I actually go to the studio all the time, but should be better about knowing when not to. I think that's another benefit of being alive longer, learning when not to do things.

The emphasis is always on action, but knowing when to restrain yourself is also so important. Recognizing when I shouldn't go in, because I know that whatever I'm going to do will be disastrous. I should just go walk in the park instead. I'm getting a bit better about that, and recognizing when that negative energy is taking over. Making art still feels very hectic and unreasonable. But that's probably just how it remains.

I was wondering if there are certain life situations that influence you, because for some people, that separation is very black and white.

It's true. I'm definitely not one of these regimented painters who can go in and know precisely what she's going to do that day. But that's okay, because I enjoy seeing the record of my energy and emotions, so even a bad studio day is still ultimately interesting. Even when it's devastating.

In your paintings, do you have marks that relate to those particular moments?

I can tell when a painting is too tight or too self-aware. That's usually when I know that things aren't going well. Sometimes, if I take a break of a couple of days and just give myself room to breathe, and just read novels, or whatever, and then get back to work, the paintings tend to be better. But they might only seem better because I was happier making them and they carry more positive associations. I think we're the worst critics, the worst viewers of our own work.

We just have no idea, really, of what anything looks like. I gave V1 Gallery the full list of all of my paintings, and was like, you guys should just curate this. Because I had something like 40 paintings, and I couldn't exhibit that many. And what they chose wasn't necessarily what I would have chosen.

I'm so interested in that idea, actually. I do have prescribed ideas about what's good in my paintings, but I try to fight them because you actually don't see anything objectively. Especially when you've been living with that shit for so long. Sometimes I'll hate a painting simply because it was in my way once. It's like, I fucking hate that painting, I had to move it five times today.

Do you get attached to your work? Do you have a hard time letting go of it?

Yes, very much, but I guess I don't, really. I sort of love reclaiming my studio. I love having my room back. Even if I don't like the painting, it's like, I'd love to see it again down the road. I love to see the work in a new environment. It's so exciting when you get to hang something else, like you're seeing it for the first time. Other people care about it, and that's still just insane to me, and it makes up for the sense of loss. But I do definitely miss certain paintings. I want them back. There are probably ten or so paintings out in the world that I would like to have back, just for myself.

Did you ever try to get any of them?

No, not at this point in my career. There is a sense that you've orphaned them. I guess you can never feel like you've orphaned anyone, because that would mean that you're dead. It's a sense of putting something out into the world, estranged, and not caring for it anymore. It's very emotional.

Do you collect other people's art? Do you enjoy other people's work in that way?

I've never bought a single piece of art. Mainly because I've never had any money. But I love trading. I have a good little collection going, mostly works on paper. I'm getting more ardent about it, insistent, really, because in my thirties, and with how many artists I know, I should have the Barnes collection by now.

This is going to be an invitation for trades when this gets printed...

I hope so! And trading a drawing is so nice because people can often undervalue works on paper. They're sometimes just the most magical things, and also easier to ship. I get really sad giving up good drawings. It's a bit harder to pin down and assess why they're working.

What sort of things do you use as reference? Does it all come from your head, or is it from photographs?

Sometimes it's photographic but the main source is memory. When Sara-Vide Ericson discussed her bear painting, she mentioned feeling that she couldn't use just any image of a bear pulled from the internet, and had to photograph one herself. I think maybe because sources are so poignant and loaded, I typically just look to other painters for guidance. Paint from paintings. But they're also mixed with memory. There's really no delineation for me, between my personal memories and memories of paintings. Sometimes I have a clear sense for a narrative, sometimes I'm guided by a color. Often it's a color.

Oh, really? I was going to ask if it ever happens that you experience something or see an image and feel like, oh, I'm going to paint this.

Yes, sometimes, but it's usually some sort of color relationship. Like a surprising shadow that sticks in your mind. Actually, I share with my friend Katie Rubright, another great painter, a love of artists' notations in their sketchbooks, where they try to describe color for later recall. They don't have their paint with them, just have a pencil. The language that they associate with a color phenomenon, that's so interesting. You see it in van Gogh's sketchbooks, "It's kind of like a buttery yellow, but it's a little bit acidic. Maybe it has a drop of piss." That kind of thing. Just trying to name a certain yellow.

It works better described than when you actually see it, right?!

Yeah, totally. That's very interesting to me. Recalling color. The failure of trying to recall a color. I also love repeated painting gestures. I think that one of the most sexual tropes in art history is people sliding their fingers into books. You see it all the time.

I've been using that gesture in my work. It's obviously vaginal. It's so sexually charged, but it's usually a stuffy patron, having his portrait done. And I wonder if everyone knew, artist and sitter alike. But the guy is also just marking his place in his book, letting you know that he's erudite and wealthy. But then there's this sexual undercurrent.

I never thought of it that way, but thank you for opening my eyes. Have you ever done sculptures?

Yeah, I have. I've never shown them.

Are you interested in doing more?

I would love to. I've been looking into boring technical questions, like where exactly to do it. I'm very interested in the entire enterprise, and I think it's so fascinating to cast and replicate a form. Replication is difficult in painting. Especially when you paint like I do. I'll occasionally try to mimic a gesture from an earlier painting and can just never get it. Or I'll attempt to bring back a composition, and it's never quite the same. So, to see a form reproduced exactly, that would be really fascinating, I think.

The technique you use seems very immediate and direct. Is that how you work? How much do you sketch?

For me, the challenge is isolating exactly what I want to be doing at any moment, and then being able to name it. Sometimes I'm after a slow, contemplative build-up of marks. Actually, maybe not contemplative, but mechanical. Thinking about nothing other than just the pleasure of this one repeated mark. At other times, it's about building through drawing. The challenge is knowing what I want.

So do you get pleasure from, let's say, the physical act of painting?

Yes.

Like, not just the end product.

Right. Oh, no, I hate the end.

Oh really?

The end is shit.

You couldn't care less?

Burn it. [laughs]

So which is the favorite part?

Selling it! What is my favorite part? I don't know, I think it depends on my mood. That's maybe why I have so much going at once, which allows me to put energy in various places. My friend, Nikki Maloof, for instance, is an amazing painter. We studied together in undergrad. We've known each other since we were 18, and so our entire development as artists has been together. It's really interesting to look at the differences in our approaches to painting. She has this very regimented process that works for her. It works for her brain. She starts with a graphite sketch and then that's translated into a small oil sketch or collage, which is then projected onto a larger canvas. She knows exactly what she'll end up with, and she does all manipulation in advance. Once it's on the canvas, it's fixed. It's not going anywhere.

That, to me, is nightmarish. The thought of that entire process. When I show her my shit, that gives her great anxiety. I think it's about figuring out your own brain chemistry and what gives you joy.

At which point did you decide, this is what I'm doing, I'm going to be an artist full-time?

My undergrad degree is from Indiana University. I only applied to one school. I didn't do particularly well in high school, so I applied to one school because it was in my state and the application was less than one page. I'm really amazed I even did that. I filled it out and then I went to school. There was this one professor... there were a few professors, actually, but this one in particular, Barry Gealt, who is emeritus now, but was teaching at the time. He's a brilliant landscape painter. He made painting feel so immediately essential. I've seen other painting programs where that urgency wasn't present. And I've wondered what would have happened to me if, by chance, I'd wound up in one of those.

It's amazing how this one person or one thing like that can really set the course for the rest of your life.

And that one person might tell you that art is important and that what you love is valuable. There are so many art schools, even in New York, that are just utter garbage. The professors don't give a shit. Maybe you've seen this thing with Columbia? The MFA program is suing the school because it's like, our professors are never here! No one is engaging us. We're paying $80,000 to go to school here, and we have no sense of camaraderie or community or anything.

Wow, that's hard.

Yeah, you can get really unlucky. It can destroy your relationship to art. This is the art world? People who aren't present and don't care? But I got lucky and fell in with this one guy. He took all of us to Italy and France. There were a couple of other great professors, too. At that school, painting was life. And it was only oil, you couldn't use acrylic. There was no option.

At this point of your career, where you are now, was this something that you were striving for?

Oh, no—I'm aiming much higher. But this is a great place to be, and it happened very quickly. I have other goals of course, but I'm very happy to be where I am.