Bony Ramirez

Cutthroat

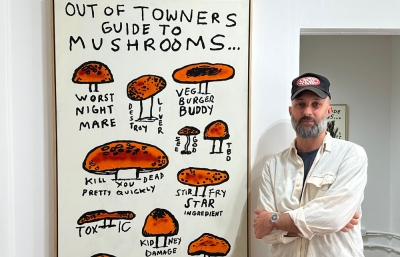

Interview by Shaquille Heath // Portrait by XEVOLEZ

At one point in our conversation, Bony Ramirez referred to his work as "cutthroat,” and I kind of fell in love with the word as soon as he uttered it. As I let it linger in my mind, it began to dance all over the images of his canvases, clearly inspired by the life Ramirez has lived. At the first meeting, it’s a bit hard to reconcile that word with the artist himself, whose empathetic spirit can be discerned just two minutes into the conversation. He is generous with the world, not just through the complex themes he explores in art, his considerations of memory, reality, and the entanglements between the two, but also with his vulnerability and willingness to share every crucial detail of that experience with us. Utilizing his once-held desire to become a children’s book illustrator, Ramirez employs a charming, almost precious style to tell dark (and dare I say cutthroat?) stories about the history and culture of the Caribbean, stereotypes and racism that he faced in America, and a depressive period when he struggled to become the artist that he is today.

It is important, as his admirers, that we consider all the roads and roadblocks that brought us his distinct style: his immigration to America as a child and the memories that linger from his home country. The thwarted opportunity to attend art school and the unique language that he created all on his own. His time spent working in construction and the skills of the trade that influence his canvases and sculptures. His experiences as an outsider, in both American culture and the art world, that created the grit and deep desire to share his talent with the world however he could. Every bit of his journey has molded his practice and created that distinct cutthroat approach, which is ingenious and sincere. Luckily, we now get to bear witness to the fruits of his ripened tree—probably freshly cut coconuts from the Dominican, of course.

Shaquille Heath: Do you remember what your first interactions were with art?

Bony Ramirez: I grew up in the Dominican Republic, and I came to this country in 2009. So the first time I was “quote-unquote" exposed to art, it was going to church as a kid, with all the paintings and sculptures of the saints. And I think I was really drawn to that. The local church in my town in the Dominican Republic has this gigantic mural in front of the church. It's not a thing here in the U.S., but in DR and a lot of parts of the Caribbean, it's normal to paint murals in churches. So our church had this long bell tower, where the patron saint of the city is painted. I think that was like my first taste of what art could look like. I used to do drawings of those things, basically, and hand them out to people at church. So everybody in town thought that I was going to become a priest, which at some point I really did consider! But yeah, I think that was my first introduction to knowing that I like art and, like, creating.

There's this thing that we do as kids, you know, more in poor towns, that whenever you want to do a copy of an artwork or something, you would take a sheet of paper and just dip it in cooking oil, and then the sheet would become really transparent. Then you would put it on top of the thing you want to trace, and when the oil dries out, you have the drawing. So I used to do that a lot too. It was dealing with, again, a lot of religious images. I grew up in a very religious household, so I think a lot of the art that I digested was, like, saints and Jesus paintings, basically.

That is such a hot tip! I also grew up very poor, and we would just hold the paper of what we wanted to trace up to the light, and your arms got really tired!

You know I don’t recommend it, haha! It’s very oily, you know. But as kids, we didn't know any better!

Yeah, it sounds very messy; that’s true. So there's some, like Aunties and Abuelas, down in DR that probably still have your artwork! That’s amazing. So, when you were drawing as a kid, did you know you wanted to become an artist? Or was that something that felt super far from your mind?

In the beginning, I knew that it was something that I liked to do for fun. I was always the creative type, but it wasn't until I got to the U.S. that I finally was exposed to art making. I got here in 2009 when I was 13, so I did eighth grade and high school here. High school is where I took art classes and really realized, “Oh, I'm really good at this! Having that second thought where the teacher says, Oh, this is actually pretty good!” Whether it was creating landscapes or like little figures and stuff, growing up, I knew that it was not something that was doable for me. I was wanting to have some kind of creative job, but to me, in my head, at that point, I just thought that artists were always the kids of rich people who could afford to live that way. Either that, or just a homeless person doing art, haha! So, you know, I wasn't either of the two. Again, this was just me in my mind. I knew that I wanted a creative job. I just didn't know what it was.

In my last year of high school, when I had to apply to college, I think that was when I had to dig deeper into what exactly I really wanted to do. I always remember that my dream job was being a children's book illustrator. So a lot of my early work, especially in high school, was a lot of these child figures and geared towards information and an education. That was my dream job at the time. Or some kind of art director of something... That, I would say, is the beginning of seeing it as a thing.

Then I did the transition of wanting to be just like a gallery artist or a full time artist once I was not able to attend college. When I got to this country, it was just me, my little brother, and my mother, so we didn't have the means to afford going to college. I always tried really hard in high school to hopefully attend, but even when I was applying, just like paying for the train to get there, it was just too much for us at that point. So I just said to myself, you know, I can't do it at the moment. Let me just create work and see what happens. And I knew that it was going to be a little bit more difficult for me as a recent immigrant and also as a self-taught artist. I tried to apply to a lot of open calls, and I really saw a response of, Oh, this kid is applying, but he doesn't have an education. I think things have changed a little bit, but at that point, it was the rule that if people went to certain schools, or if you go to art school in general, that's a sign that you are serious. And because “of course, good art isn't in the eye of the beholder"—what seals the stamp is that there's a school that's behind you approving that the work is good. You have the kids from Yale or Columbia—those are the ones that are considered the best artists because they go to the best schools.

So again, for me, I knew it was going to be more difficult. But on a more personal note, it was a very depressing page in my life. Mainly for that reason, I felt I had this talent that I wanted to share with everybody but just couldn't. So I think I was just not in the best place mentally. But I just said, Okay, let me just make the work. Let me just share my art on social media, and I think that's where things started.

I'm sure that was a really hard time. And you're right, the art world has gotten better, but it still feels like people at the top are in that same pipeline. I'm always drawn to artists and people who come the hard way. I think there's something so special about those who are self-taught. Like you were saying, you can truly allow your creativity to be unfazed and shaped by what your classmates are doing or what the professors are saying. Is that something that you feel in hindsight?

100%. Now I think I understand why the universe didn’t let me through school. At that point, I didn't understand. I was like, “Oh my God, my life is over.” But now I understand why I went through that. It’s what made me push harder as a person. On the technical side, I had to come up with the language that I have now on my own. I think that's where the uniqueness came from. Because material wise, I had to just work with what I had. I used to make my own panels. I used to buy these canvases from thrift stores and just paint over them. So it literally shaped my practice—literally not going to school and working with what I had.

A lot of those hardships that I went through are a lot of the stories that I tell through my works now. Now I'm in a better place mentally and can talk about how it really shaped my life and my career. I think maybe I would not have tried as hard if I had a degree. And maybe if I had a teacher or somebody guiding me in the way of doing things, I probably wouldn't do what I am doing today. Essentially, I tried to teach myself what I thought people were being taught in school. Later, I found out that a lot of artists are not taught about galleries and art fairs, and I thought that's what I was missing out on. But now that I have ended up in the art world, I know how to navigate these phases. I thought people were being taught these things, so not going to school was probably the biggest blessing in disguise. I just didn't understand at that point.

There are bigger things; things happen for a reason, literally. Because, again, I was really, really heartbroken. But I'm like, Wait, this is literally what got me to where I am now. After that experience, I just trust the universe.

The universe really does work in mysterious ways. And some of those lessons really are tough. You can see your trust in the process. You're really not scared to kind of play with the macabre, whether that's slaughter or sadness, like featuring knives and machetes.

Do you think exploring that dark time in your life has been a form of therapy? Or is it more of a fascination?

Do you think exploring that dark time in your life has been a form of therapy? Or is it more of a fascination?

I think it's both. At that point in my life, I had a, I don't wanna say, dark mindset, but a dark period of my life because there was a lot of anger inside me, mainly from the idea that I couldn’t do anything about the situation. So a lot of those experiences come out now in the work because one of my big frustrations was feeling like I had so much to say and didn't have the platform to do it. Now that I have the platform, I'm saying the things that I wanted to say then.

The nature of my work when looking at the figures can be so cute and sometimes simple that I like to break that by bringing on more serious compositions, especially when I paint the kids. I have also been a fan of pushing those limits and just not censoring myself in that way. It can be a little tricky sometimes. I'm also so influenced by the Renaissance as well as 18th and 19th century works. Our idea of death as a society has, of course, changed since that time. If we're okay with these classical painters doing it, why can't I do it also? A lot of those more bloody paintings or strong compositions really come from trying to express those feelings. I really want them to be as quote-unquote as cutthroat as they seem. There is also a historical context in the work with colonialism. At times, I think I don't want to, you know, make it less than what it was. I don't want to sugarcoat them in any kind of way. I want to give it to the viewer as it is.

I love that you don't want to sugarcoat it. What's so dope about your work is that it is so approachable. But once you look closely, your brain starts to turn.

That's something that I had to be careful with. Because there's a style, like you said. Sometimes, when you see the figure and what's happening, that can be so cute. But I don't want it taken as that. Even with emotions, I hardly paint a smile because that makes it too playful. I think most of the paintings are serious, sad, or, you know, some kind of strong emotion. My work is definitely made up of a lot of strong emotions. I think about a lot of the shows that I do, and I don't want it to be trauma, trauma, trauma. So there's at least one or two paintings that are a bit more like leisure paintings. It's okay if we’re just happy and doing nothing. So I have to sometimes just pace myself because it can’t be trauma, trauma, trauma. You know, there's space to rest and not to think about it.

Absolutely. Within your paintings, you sometimes feature your characters as kind of hybrid animals, like part human and part crocodile or part human and part leopard. Can you talk to me about those compositions and the inspirations?

So it started with one work that's currently at the Pérez Art Museum. That was the first time that I kind of delved into the more magical realism part of my work. At the moment, it felt like, Oh my god, what am I doing? Because I didn't want people to lose me in the figures. One piece is called Fiera: Views From the Outside. I think I was trying to create a stereotype of how we, specifically, for Caribbean immigrants, are often seen in the U.S.—that we’re these loud, disorganized, savage animals that don’t have manners. So I think I was trying to come up with this animal-hybrid-human-figure that would encompass that stereotype—a savage animal just going crazy. It started with that work, and I think recently I extended it more in my latest solo show. Usually, they are animals that have this depiction of being very savage or dangerous. And then just mixing it with the figures in this conversation about how we are seen a lot of times.

Going to school, people were always like, “Oh, Dominicans are so loud!” Or we were separated as “the bilinguals"—I was in an ESL program. So I think that othered feeling is what comes up in these compositions. They all have this title, "fiera," which almost means like a violent animal. I'm not sure if there is a word for that in English. So every time I've done these pieces, they have the "fiera” and then their actual title, to give them the same kind of theme and family.

Oh, I love that! Speaking of bilingualism, you have a work titled El Bilingüe (Self-Portrait as a Bull) that showcases your amazing sculpture practice. Why the bull as the animal you chose to be a depiction of yourself?

On the sculpture practice, specifically these taxidermy animal practices, they're kind of my way of being a little bit more open and personal with my works. I think my paintings always include a part of myself, though for me, sometimes it's hard to open up about specific parts of my life. And my way of therapy is to do it through these taxidermy sculptures. A lot of animals that I use, especially for this practice, are animals that I grew up around. So it's almost like putting myself in these animals that I have a relationship with. I'm never going to use a jaguar or tigers in these sculptures because I have no connection to them. So it usually would be the bulls, cows, roosters, the horses. For example, El Bilingüe had a specific story about when I first came to this country and the bilingual program. But again, with them, I tell very specific stories that are just for myself. A lot of the paintings have larger group themes that we can all relate to. But the sculptures are kind of my way of talking just about myself. I feel like I should open up about different things, and it also helps people know me a little bit more. They are still a bit difficult to talk about because I don't want to give too much information. But essentially, those practices are always self portraits. They're always going to be self portraits.

So are those extremely hard to make, like, internally and emotionally?

I think the reflection part is easy while I'm making the work. I think it got hard specifically for the show because there were so many people there that it's hard to talk about it. The real challenge comes when I have to explain it. That's kind of what we went through when we did the press release—I just went, “Oh yeah, they're just self-portraits.” But then I did a lot of artist talks and tours, and people asked me what it meant, and I had to just open up. I know my artist brain will always get in the way of my human brain, if that makes sense. I will, just for the sake of art, open up. If I can trick my brain into making it seem like I'm explaining art, then I can open up about those things. Because, again, I think there are a lot of things that I just keep to myself, especially in that period of my life. It was just me in my head. I didn't have anybody to talk about art or anything, to be honest. I was just working construction.

Correct me if I'm wrong, but you haven’t gone back to the DR since you moved at 13, correct? You have such vivid memories, even at 13!

Correct, I haven’t been back. I think a big part of my work and my practice is working from memory. A lot of times it's very cultural or historical, but a lot of things that I portray are just things that I remember as a kid. So it's kind of also my way of holding on to those memories. In my last show, a lot of the works touched upon childhood memories, and it's kind of my way of holding on to them. But I think not going back helped me visualize things in a different way. It helps me bend the figures, and I also bend reality a little bit. Like with the light or composition of things because I don't have a vivid, vivid, vivid memory of it, just like loosely. So I can just go from that and make it my own. But again, mainly, it helps me hold on to those memories by putting them into the work.

I do know that once I go back, I'll probably remember things that I forgot about, and then that can feed other works. But also, I don't want to be too influenced by reality. Not that I want to keep it in an ignorant way. But I think it's good that, for now at least, there's that barrier of meeting my memories and the reality of things.

Bony Ramirez has a new body of work on view now at the Newark Museum of Art. Hear more from Ramirez on the Radio Juxtapoz podcast Episode 089. This interview was originally published in our SPRING 2024 Quarterly.