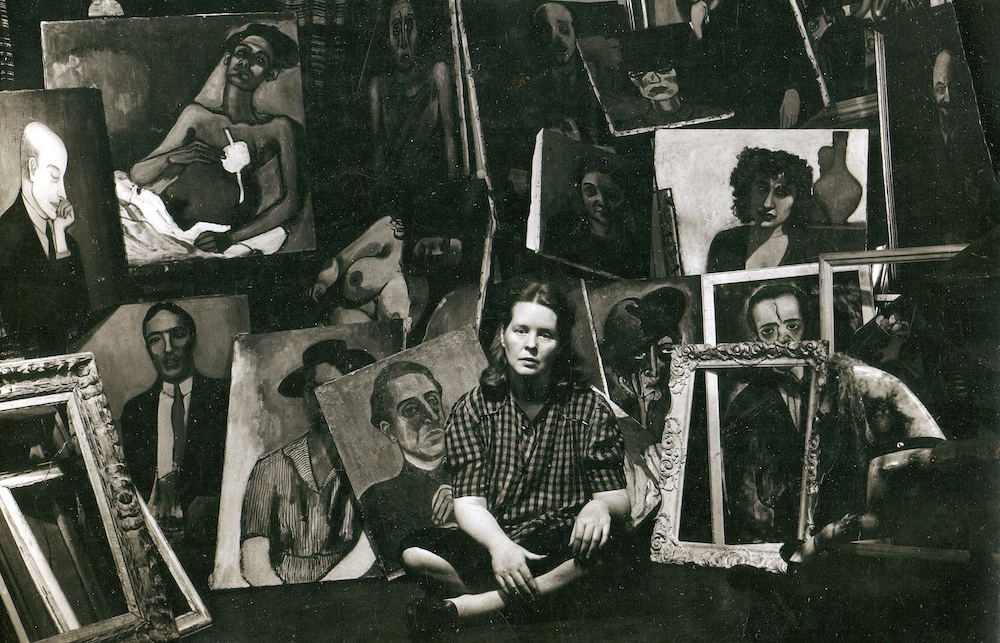

Alice Neel

People Come First

Interview by Gwynned Vitello

The twentieth-century figurative painter Alice Neel reflected that, “My psychiatrist once told me that I got interested in painting portraits because I liked to watch my mother’s face. It had dominion over me. Since she was so unpredictable, I watched her face to see whether she approved of things or not.” Neel shared that matriarchal strength, but channeled it into a passion for turning oil paint into pictures that were not pretty or precious, but icons of indelible insight. Her subjects were Harlem neighbors, Cuban neighborhoods, writers, activists and notably, mothers. She was a trailblazer, as noted by the three young portrait artists in this piece, who offered their appreciations. I spoke with Lauren Palmor, Assistant Curator at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco about Alice Neel: People Come First, opening at the de Young Museum March 12, 2022.

Gwynned Vitello: Can you tell me about the influence of Alice Neel’s teacher from the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, Robert Henri? His manifesto, “Life and art cannot be disassociated, nor can any artist… produce a line of ‘sheer beauty’, i.e., a line disassociated from human feeling,” seemed to guide her style, and eventually, her choice of subjects.

Lauren Palmor: Neel’s humanism and realism were defined by her time at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now the the Moore College of Art and Design), between 1921 and 1925. There, she did absorb the style and philosophy of one of the school’s most influential teachers, Robert Henri, whose book, The Art Spirit, made a serious impact on Neel’s artistic outlook. She also absorbed his work, with its devotion to the urban poor and empathy for his subjects. Her own practice rhymes with one of his declarations, “When the artist is alive in any person… he becomes an inventive, searching, daring, self-expressing creature… He disturbs, upsets, enlightens and opens the way for a better understanding.”

She was adamant about how, “My life in Cuba had much more to do with my later psychology. It conditioned me a lot.” What brought Neel there and how did it shape her?

In 1924, Neel met Carlos Enriquez at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. He was an artist from a prominent Cuban family—handsome and charming with leftist leanings who socialized with the Cuban avant-garde. They married in 1925 and left for Cuba soon after, and, after initially staying with his wealthy family, moved into their own apartment in Havana’s La Vibora district, where Neel witnessed extreme poverty and began painting people she met on the streets.

Neel’s Cuban period made an indelible impact. In addition to painting her earliest pictures of the Black and Brown sitters who inhabited the world around her, she also enjoyed her first public exhibition. Through Enriquez, she also met prominent leftist intellectuals and artists who deepened her sensitivities to the plight of the working class. During this period, Neel explored more deeply the political aspects of painting people.

After leaving Cuba, she experienced what was considered a mental breakdown. Did this follow her throughout life, and how do you think that impacted her? She certainly didn’t paint “pretty,” but portrayed the proverbial underbelly without judgment.

Neel experienced a number of personal tragedies and companion mental health crises in the early decades of her career. Between the death of her first daughter, Santillan, and estrangement from Isabetta, her second, those first years were colored by strife, poverty and loss. After a 1930 nervous breakdown, Neel received dehumanizing psychiatric treatment, which surely deepened her sensitivity to human suffering and likely contributed to her interest in the trauma and pain of others, such as the psychologically wrought Randall in Extremis from 1960, a portrait of physical and mental distress or the representation of domestic abuse on display in 1949’s Peggy.

Were mothers and children favorite subjects because she was a young, often single, mother who painted those around her?

Pregnancy, postpartum and motherhood are major themes throughout Neel’s oeuvre, unsurprising given her own challenges as a young mother. From losing her daughters, one to illness and the other to estrangement, to the difficulties raising her two sons, Neel’s personal experience opened her to the artistic possibilities of representing maternity without idealization. She was also attracted to how it transforms the body, from the exaggerated curves of pregnancy and fullness and strain of nursing, to the complete exhaustion and physical depletion written across another young mother’s face. In addition to exploring the body, Neel possessed a distinct ability to penetrate the psychological and emotional aspects. Her struggle with being an artist and mother, which she called the “awful dichotomy,” came through in her work as early as the 1920s—decades before the feminists of the ’70s considered the theme.

How did she approach the children and mothers who sat for her paintings? Did she have relationships with them prior to or after the sittings?

Some of them were family friends, while others occupied less intimate roles in the artist’s life, such as Carmen Gordon, a Haitian woman who cleaned and babysat for Neel and her daughter-in-law, as well as the subject of Pregnant Maria, a woman who was friends with some of Neel’s student neighbors in her West 107th Street building. If she found someone’s appearance striking, she wouldn't hesitate to invite them to sit for her. Even then, Neel was able to cultivate intimacy in the studio setting. She spoke openly about her views and experiences, and many sitters describe her disarming storytelling.

When did she start painting nudes, and what was her particular fascination with the genre? Was that unconventional for a woman during that period?

Neel painted nudes early on, and her interest in exploring the dimensions of the human body persisted throughout her life. While the nude could be viewed as unusual for a woman of that time, she pushed boundaries further by expanding her practice to destabilize the traditional nude figures of Western art history, painting nude men, women and children without sentimentality. Neel played with the possibilities, recasting a man as a confident odalisque or exploring the swollen curves of pregnancy, studies that were even more radical because of her position as a woman. She inhabited the type of body that historically had been stripped down and objectified. Her nudes were not painted for the sensual pleasure of the artist or viewer, but out of real human interest.

When did she start painting LGBTQ subjects? Once again, that seems almost audacious for the time, especially because many of them are so candid. Did she approach her subjects and did having a portrait done by her have a kind of cache?

Neel’s 1932 watercolor and collage of Christopher Lazare, a friend and writer for the WPA, represents one her earliest LGBTQ subjects. Unusual for its time, her four-part image of him explicitly references his sexual preferences and alludes to his various public and private personas. The page is flanked by images of him in a striped shirt and checkered hat, while the private Lazare leans dreamily dressed in a robe that reveals sores on his chest. In the center, he appears in profile, hunched and lost in thought, in contrast to the phallus that sprouts from the top of his head—the likely source of his distraction. Neel remained engaged with LGBTQ subjects, and as the conversation about queer identities shifted over the decades, so too, did her depictions of gender performance and relationships. There is a world of difference between the playfully analytical study of Lazere and Neel’s much later double portrait of a couple, 1978’s Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian, a portrayal of earnest affection that stands apart as one of the happier works in the exhibition.

When did she achieve commercial and critical success?

Neel’s accomplishments were under-appreciated until the 1970s when she finally received an outpouring of recognition. Much of this belated acknowledgement was intertwined with progress made by the feminist movement. By 1984, she had risen to the ranks of national celebrity, making two sparkling appearances on Johnny Carson’s Tonight show. By the time of her passing later that year, she remained a “painter’s painter,” and posthumously, is widely celebrated for her remarkable vision, pictorial power and radical humanism.

People may not know that she was a great landscape and still life painter too. What are some special qualities she gave to that genre, and do you have a favorite?

Like her pictures of people, Neel infused landscapes and still life with psychological tension, symbolism and pure affection. 1968’s Richard Gibbs is a rare example of her interests in the figure, landscapes and still life—all three elements tied together by psychology and painterly energy. Gibbs is placed both outside and inside at the same time, sitting on a grassy landscape on one side, and beside a window sill holding a potted vine on the other. He looks directly at the viewer, and we wonder if he is seated indoors, dreaming of an open field—or outdoors thinking of his chair by the apartment window? Here, Neel draws upon her sensitivities toward people, places and things, offering an arresting view of her sitter’s imagination.

So, what about her reputation as a representational painter who used abstract elements, but early on stated, “I am against abstract and non-objective art because such art shows a hatred for human beings.”

Although she remained steadfast in her dedication to the figure, Neel incorporated abstract gestures in service to her “pictures of people.” She criticized the lifelessness of abstract painting, and in her hands, abstract gestures were used to suffuse her canvases with additional vitality and vigor. Bravura brushstrokes or excessive color fields can be found throughout Neel’s work, emphasizing a sitter’s emotions or alluding to the larger setting beyond the canvas.

There have been references to Van Gogh in her work, but who else influenced her?

Neel denied having direct influences, though she professed admiration for Van Gogh, Goya and El Greco. She spoke highly of Cezanne’s portraits, though his influences can be felt in her cityscapes and still lifes too, where she masterfully incorporates individual elements, working her broad brushstrokes into a mosaic of forms and effects.

How will the show be installed? How does it start and end, and is there anything unique about this iteration of the exhibition?

The de Young presentation will begin with an introduction, then immediately take us to Neel’s New York City, a place where she lived and worked for most of her life. The galleries follow with Counter/Culture, the Human Comedy, Art as History, San Francisco, Motherhood, Home and “Good Abstract Qualities.” While the core remains in place from the show’s debut at the Met, our presentation enjoys the addition of a small section devoted to her visits to San Francisco in 1967 and 1969, spending time with her son Hartley and future daughter-in-law Ginny, who became a frequent subject. 1969’s Ginny in Blue Shirt was painted in the couple’s apartment near Buena Vista Park and it will be hung beside footage shot by Harley with a 16mm Bolex, offering the rare opportunity of watching the artist at work, while viewing the results.

What was your assessment of Alice Neel when you started out doing research, and what surprised you at the end?

I began thinking about the exhibition when I was pregnant, and her work carried me through the early months of motherhood. I came to more fully understand the unvarnished honesty of her maternal subjects. Only after moving through the stages of pregnancy and birth could I fully appreciate the raw, unidealized and profoundly empathetic aspects of her work on this theme. Neel put it best: “Sissies never showed it, but it’s a basic fact of life.”

Alice Neel: People Come First will be on view at de Young museum in San Francisco from March 12–July 10, 2022. Read our extensive conversations with Jenna Gribbon, Dominic Chambers and Esiri Eherience-Essi on Alice Neel on Juxtapoz.com this spring.