If every picture tells a story, then every article of clothing, with its drape, rustle, and texture, can visually merge into a work of historical fiction as well as an absorbing action movie. Fashioning San Francisco: A Century of Style at the de Young Museum in San Francisco spans the city’s colorful history from post-earthquake to the present. I spoke to curator Laura Camerlengo about producing and directing this stunning show.

Gwynned Vitello: It would be interesting to know about the fashion and textile collections housed in museums. Is it common to have such acquisitions, and how are they compiled?

Laura Camerlengo: The Fine Arts Museum has a collection of about 14,000+ costume and textile artworks, spanning some 125 countries or cultures. It includes Coptic textile fragments, European tapestries, Anatolian Kilims, and great holdings of 20th and 21st century couture. There are several comparable collections in different museums around the US, the best known of which is probably at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Many were outgrowths of the early foundations of US museums and an interest in creating collections that could be used for educational purposes, particularly as reference material for textile artists, makers, and designers. Museums were coming to the fore in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, so it coincided with a national interest in developing textile industries and the idea of museums as repositories supporting that objective.

Great, this gives a better understanding of the importance of fashion in art institutions. How did this show come about?

It started with my predecessor, Jill D’Alessandro, now at the Denver Museum of Art. We were curating together, and I took it over about a year and a half ago. Our three full-time conservators, led by Beth Suhey, have done tremendous work, spending hundreds of hours conserving the pieces that will be on view, many for the first time since they became part of our collection. The show spans from just after the 1906 earthquake to now.

The idea is to situate each section within a larger history of fashion and development in the city. The first looks at the return of fashion after the disaster and how fashion was used to project a cosmopolitan image and a sense of resiliency within San Francisco to bolster the city and the economy. Temporary shops were set up to bring clothing into the city, and then we see the rebuilding of the grand department stores and the revitalization of downtown.

So, pop-ups gave way to department stores. How long did it take for this to happen?

It was around 1908, when they imported clothing from New York and Europe; that kicks off the exhibition, and each section builds from that narrative. We then go into the Little Black Dress, the image of modernity—this idea of black emerging as a color in fashion after the tremendous death toll of the First World War. You can see a parallel in all the disaster that happened in San Francisco as a color that would have local resonance. Next, we go into the ball gowns and evening wear. The city always had a vibrant philanthropic sector going back to the 19th century. In fact, the lack of government infrastructure really facilitated a lot of charitable efforts.

Ah, this was more than the earthquake, like it was going back to the Gold Rush and the Wild West?

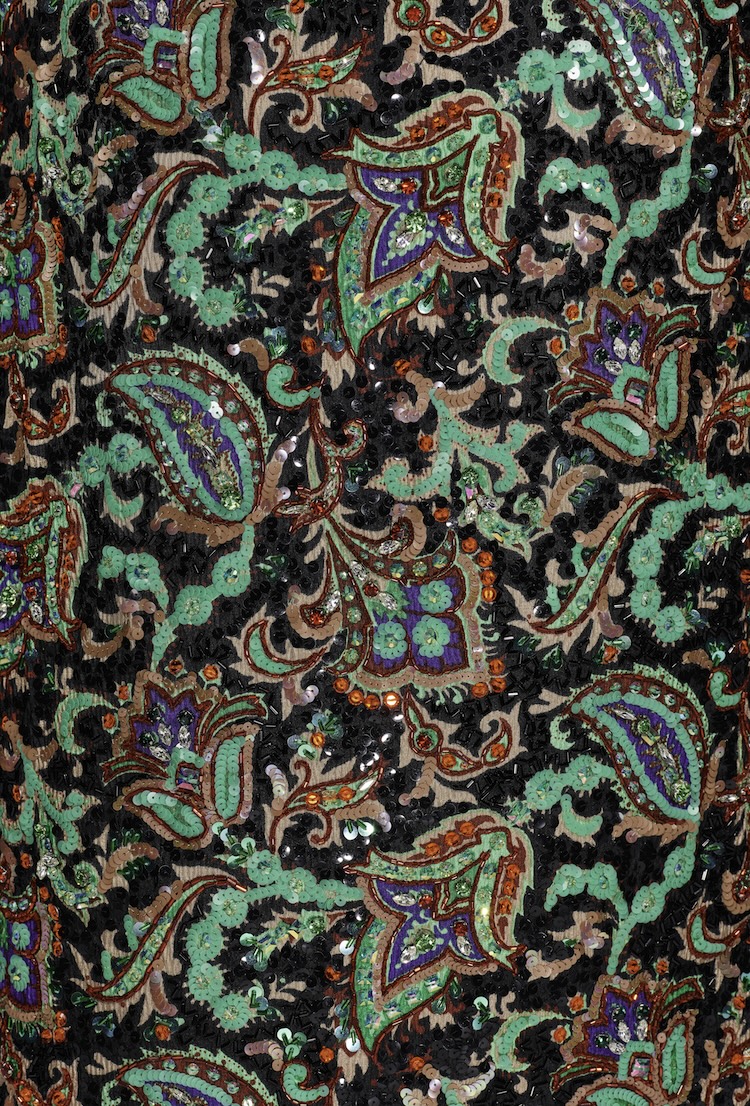

Yes, a lot of charitable giving took place, and it was very lively. You could say the industry of philanthropy really encouraged the wearing of great fashion in the city, particularly French haute couture from a lot of the department stores, which is where we get into the section called After the Ball. There are all these great designers like Christian Dior, Yves Saint Laurent, and Alexander McQueen, but we also feature the women who wore them, a theme throughout the exhibition.

I’m glad you also present that personal aspect.

We’ll identify who wore the item, including where, if we know. Using a lot of reference photography and news clippings, each outfit is styled to look like how the person wore it. We found Elizabeth DeSole, a wig maker from New York who works with the Costume Institute. She created paper wigs that look like the hairstyles worn by the featured women.

I just assumed you would have the usual mannequin heads.

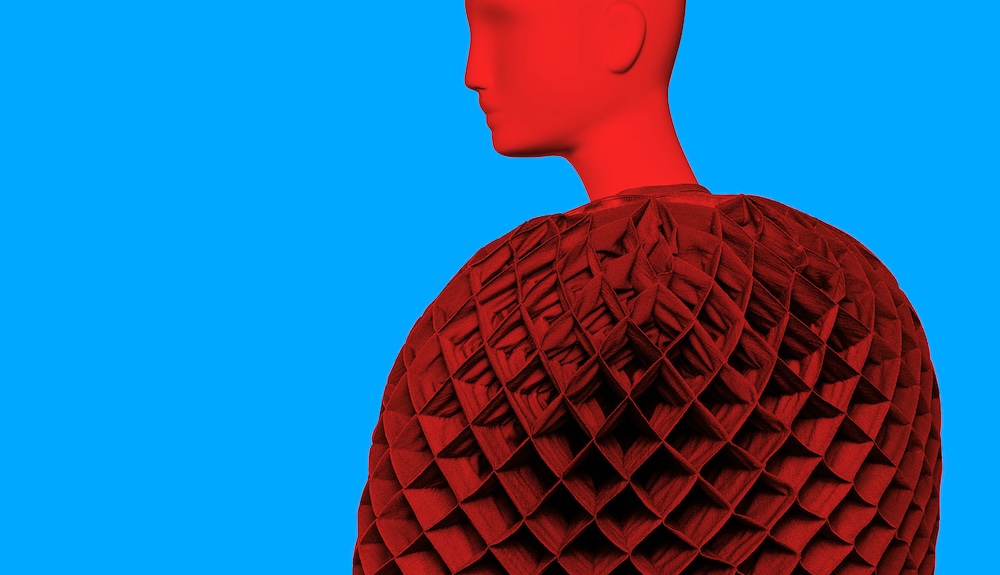

The mannequins will be in two tones of gray or black, and then the paper wigs are painted to match those colors. For example, a black mannequin gets a black wig, which serves as a mount for the costume, so you get the essence of the wearer—personal, yet universal.

While not duplicating the person who originally wore the clothing, you still pay tribute! How did Elizabeth create the looks?

We worked with her for months, supplying images from five years of research from newspapers and personal archives, compiling everything on a spreadsheet, from which she made samples, followed by conversations on Zoom. It was really fun, and now we have about 30 wigs.

How many ensembles are in the show, and how many items? And shoes will have their own space?

There will be 82 ensembles, and with the shoes, a total of 115 objects. We initially thought it would be fun to do jewelry, gloves, and the whole nine yards, but as we started testing, we realized the fashions were so extraordinary that accessories would be a distraction, though if there happened to be a piece of jewelry originally pinned on a lapel, that would be included. Since the wigs lend a sense of the person and shoes spanning the same period, they could be shown separately.

Rather than displaying clothing from a designer's specific collection, you’re telling stories about a city and the women who represent(ed) it. What about the backdrops?

Exhibition designer Julia Pike researched the landscape and architecture of San Francisco and thought about certain types of clothing connecting to the scenery of the city. The all-black section, for example, appears with Gothic architecture, and the 1906 section evokes the Palace of Fine Arts, site of the Panama Pacific Exhibition. Ballgowns are shown against a depiction of the Opera House, and for the power suits and working women, we have a facade that looks like the old I. Magnin store (which Christian Dior dubbed the White Marble Palace.) It was important to highlight the stores and elevate the stories of the retailers, especially the small businesses, as we connect national and international stories. We also talked to local retailers like Modern Appealing Clothing and Susan’s, as well as lenders like Sherri McMullen, who has several Christopher John Rogers and Christine Suppes, who has pieces from Rodarte.

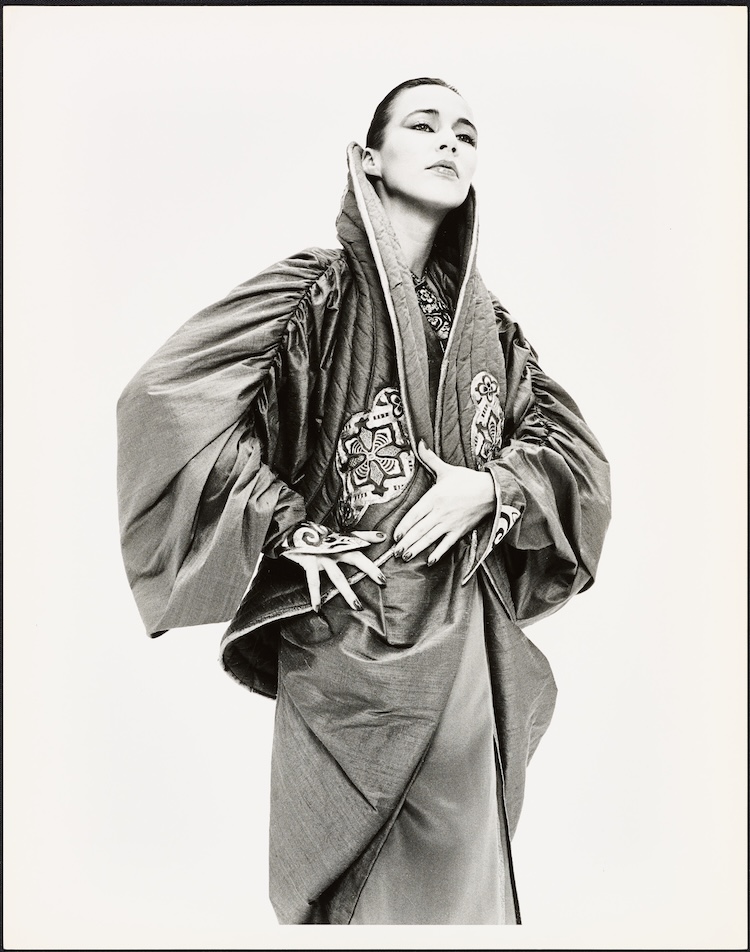

Tell me about the avant-garde section, which I’m guessing includes Japanese designers.

We connect that to modernist architecture, so St. Mary’s Cathedral provides the backdrop. Designers like Rei Kawakubo, Issey Miyake, Junya Watanabe, and Yohji Yamamoto are featured, as is Kaisik Wong, born and raised here. This section showcases global aesthetic influences and interrogates cultural borrowing in fashion, giving examples where Western designers looked to cultures outside of their own for inspiration.

That opens up a huge discussion, and I know the museum has addressed staffing in order to widen its scope and be more representative.

I worked closely with Abram Jackson, Director of Interpretation, as the population of San Francisco has always been diverse. By the 19th century, we were more multicultural than a lot of the major cities on the East Coast, and many current scholars have described it as culturally fluid. So we think about that and ask questions about the practice of cultural appropriation. We do have some gorgeous garments from the Russian collection by Yves Saint Laurent, who is very much connected to the idea of diversity, although that narrative gets complicated considering he was part of the French ruling classes in Algeria, borrowing from cultures France has colonized. This doesn’t necessarily cast judgment, but it considers the dynamics of power. Yet this collection of amazing fabrics, textures, and embellishments is attributed with reviving the couture industry.

I’m getting a better concept of the lay-out, but how is each tableau produced and how?

You just heard about paper wigs, and now I’ll tell you about the curtains, which are creamy white, gauzy, and sheer. They’re against a blue-gray wall, so you get the outlines and shapes of buildings, emanating this misty feel, all thanks to our exhibition design team. Drawn on the semi-transparent curtain are silhouettes of different architectural shapes with big cutouts showing a mannequin, really a construction piece that will bring San Francisco inside the museum.

And you end with the shoes!

Our designer has made the space look like a department store, with shelves designed to look like a display case and new seating to make you feel like you’re in the shoe section.

This all goes way beyond darkened lighting and lavender walls. It will be fun, and it will be enlightening.

We could have done this show, like, five times over. What I envision is reintroducing the collection to the public and telling new and exciting stories to our audiences. We have a lot to work with and a lot to share!

Fashioning San Francisco: A Century of Style is on view at the de Young museum through August 11, 2024.