Artist and curator Ever Velasquez first visited Charlie James Gallery in 2018 to support her friend, Shizu Saldamando’s solo exhibit, To Return. A colored pencil portrait of Velasquez called La Ever, Chica Malcriada which hung in the main gallery was the featured image in the show’s marketing and the first piece sold to CJG’s best collector. Today, Velasquez manages the gallery that’s become ground zero for BIPOC and LGBTQ+ exhibitions and artist representation in Los Angeles. We sat down for a punk rock lunch at Toi in West Hollywood and chatted about her strong influence in the Los Angeles art scene.

Trina Calderón: How did your role with Charlie James evolve after you met at Shizu’s show?

Ever Velasquez: I kept running into Charlie at different art events and we would sidebar, “What do you think of that show, who do you think is a standout?” I would tell him, “There’s these two or three, these are the ones to watch. I have a good feeling about these.” Sure enough, anybody that I mentioned went on to do well. I started helping at the gallery, and at the fairs and now I’m the gallery manager. Charlie says I’m the eye of the gallery.

Do you and Charlie share the same taste?

What sets Charlie aside from most galleries is he came from tech, and he worked, traveled, and lived throughout Latin America and Europe. When he was in Latin America he really dove into the culture. I think for being a straight white man, he really understands us, our culture, and what’s good or isn’t good. I think a lot of galleries are ready to scoop up brown artists, while Charlie will look and say something like, “Mmm, not necessarily for us right here.” I think it was the perfect combination and I came to the right gallery, with the right principles. The first artist he started to represent was Nery Gabriel Lemus. He had his eye on brown art before many other people and it made sense to be there. Sometimes our opinions differ, but it’s always positive.

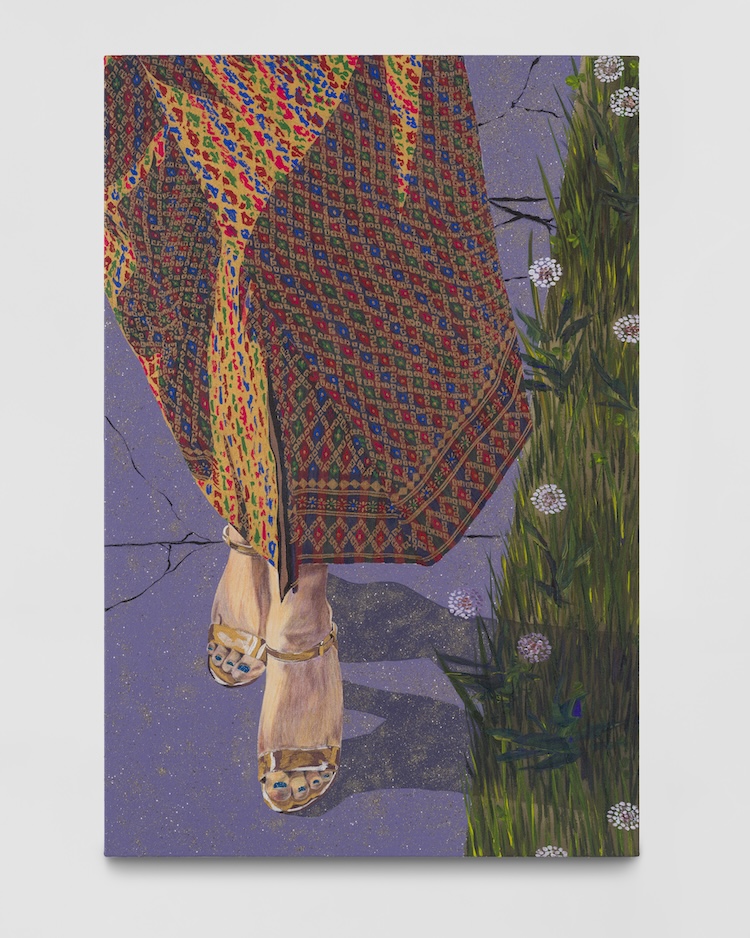

(La Ever, Chica Malcriada)

How did you become interested in art?

There are very few people who know who they are early in life, I think I’m one of those people. As a kid, I was a big daydreamer, which was a problem at school. I grew up in a home with very low resources. But I had dreams, I had to tell my mom things like, for my quinceañera, “It’s going to be at the Madonna Inn and I want a Halston Original, not a Halston from Sears.” My mom was like, “Okay, that’s beautiful, how do you think this is going to happen?” I was like, “We have ten years so if I work hard at the swap meet like I do, I can make these things happen.” I’ve always had this view that I can make things happen with the resources around me. Early on, if we were going to museums on a field trip, I volunteered my mom as a chaperone. I was exposed to art young, I knew what I liked immediately and would immerse myself into an artist’s body of work.

How did you know what you liked?

As a kid, not only was I a record hound but also a paper hound. There would always be magazines that people would discard, and I would save them, which led to my artwork as a collage artist. That was my exposure, as well as PBS, and going to museums and looking. I would tell my mom, “Okay, this is what I like, and this is why I like this,” and I feel that art is supposed to always trigger emotion.

Your instinct about art is also spiritual. How did you become a practitioner in the African Yoruba Orisha tradition?

I know now that I was born with a natural gift. Very early on as a child, I would have vivid dreams about things that would happen. Or I would see people and tell my mom, I would read them, “Oh, that person is sick,” or “That person will die soon.” As a kid I already knew how to work with herbs, I knew what flowers I could eat. From my mother’s lineage, I come from a long line of curandera medicine, but I wasn’t allowed to develop it. I noticed when I went against my gut instinct or the voices that would tell me things bad things would happen.

Learning the practice, I was told, “This was something you were born to do, this is going to move very quickly for you because you finally opened the door. As long as you stay humble and do what you’re supposed to be doing and listen to your godmother, things will move.” I was having intense dreams with water all the time and then Orisa started coming to me, specifically [ocean goddess] Yemayá came to me first, asking for me to produce an artwork in their name. I created this beautiful collage and soon after the river goddess Oshun was like, don’t forget about me, I want one too. I am a crowned daughter of Obatala and Oshun in Lucumí.

What else informs the way you see?

For me, early on, listening to punk. And I was listening to early salsa records; my parents were big into Fania specifically because when they met here in LA, Fania started doing the tours. What people don’t know is that LA was very salsa-heavy, and all the greats played here. That’s what they did when they dated, that’s what they’d go see. I always had that background, Mexican music from my mom, and my dad’s Ecuadorian, so all that salsa meringue. I found punk rock, hip hop, shoegaze, meta, and power violence myself. I listened to a lot of college radio. That saved me, from working in the swap meet, being a brown person, and understanding DIY without even knowing it was DIY. Like, “I’ve been doing this all my life.”

I was making my own zines, little art books, and random angry girl thoughts. I think Riot grrrl was pivotal. Early Riot grrrl years, it was always like you’d run into white girls at shows, and they would let you know that you weren’t supposed to be there. It’s kind of like that today. You know what I mean, is it feminism or is it white feminism? Language is the tool of the oppressor and I have always had a lot of it directed at me.

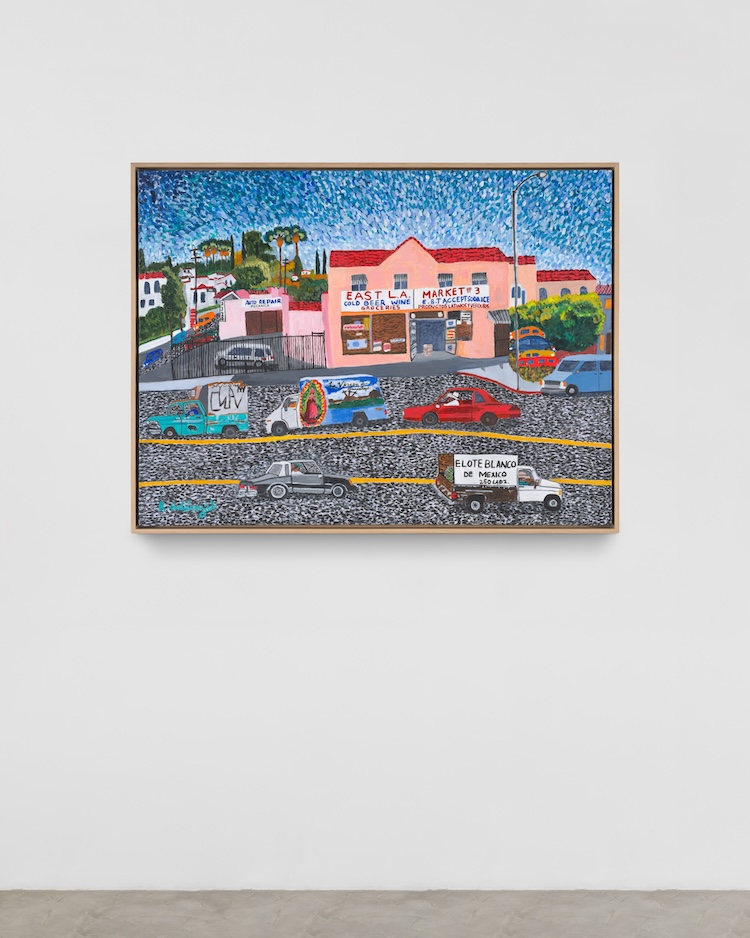

(Charlie James Gallery, Chinatown, Los Angeles)

And now you’re the poetry editor of DIY punk rock zine Razorcake.

Yes. Back in the day in Razorcake, there was a bottom footnote: “You live in the LA area and would like to volunteer at Razorcake, come by.” I sent them an email, ‘Hey I’m going to come by’ and the funniest thing was, they saw my name and assumed that I was going to be a man. And that usually happens because they assume it’s Everett or Eduardo. I showed up and they were like, “Oh, you’re a female, and I was all, ‘Yeah.”

It hit everybody hard when Trump was elected; we didn’t know it was going to happen and some of us had to remind others that we always have to have this resilience. I approached Todd Taylor, and I told him that I felt we needed this poetry page for people to undrown their feelings, and he’s like, “Cool. You’re going to be the editor and do all of it? You can have two pages.” Puro Pinche Poetry Gritos Del Barrio started and I muscled my friend Nicole to be co-editor at the time and RoQue Torres has illustrated the column since.

The artists who show at CJG inspire important conversations around resistance and decolonization. What’s your process in knowing who these artists are and helping them exhibit?

It’s two things. It’s having the eye of what I like very quickly. The spirituality ties in where it’s like sometimes I get, They’re going to cause you problems, and then I have to move it along. It comes down to creating that community, so I engage with the artists. When I create the group shows or go for studio visits, I already know who they are. I’m paying attention to the work and I’m here to have a dialogue with them because for it to work, we’re going to have to be able to break bread and have me help you. This is a family.

Freedom Portals, the show with Patrisse Cullors and noé olivas, was important not only from a point of decolonization but also in community healing and unity. That show is a perfect example of how spiritual connection plays into the work I do. I first met Patrisse in person during my iyaboraje (elder initiation year in white.) I knew she was an elder so I came to salute her properly. Soon after my spiritual year, we opened a show with Rashuan Rucker that, to this day, holds a special place for me. I asked Charlie to invite Patrisse and she came with the Crenshaw Dairy Mart (CDM) family.

We expressed wanting to work together and scheduled Freedom Portals. Then the murder of Patrisse’s cousin by the LAPD happened. Our number one focus was to make sure Patrisse was okay. We met, and the strength she showed that day and every day after is something I can’t describe. She still wanted to do the show and we left it at that. I felt it would be a spiritual show, we needed to be patient and it would be beautiful. I had faith in the spirits walking with me that this time was a time of healing for her and all of us. Freedom Portals delivered that and so much more.

Is there a “type” of artist that shows at CJG?

It’s about making work that will stand the test of time. When it was made and what was happening is how it will be part of art history. When you look back, what are the artists of this time making? Who are they? What were they talking about? What were their conversations? When it comes to the program at CJG, everybody’s doing that work.

What’s your method for bringing in new artists?

For me, and with Charlie, you come to the gallery and it’s a different vibe. We say hi to you. We’re happy to see you. We’re excited to talk about the art, where in most places, it’s like (she makes a frowning face), You’re lucky if they look over at you. That’s important, and to be able to speak openly, all the artists have been able to speak openly.

Whose artwork excites you right now?

I’m excited about the work and the community that CJG, Rafa Esparza, Summaeverythang (Lauren Halsey), CDM, Ozzie Juarez, and Tlaloc Studios continue to create. We got to show Elmer Guevara and Narciso Martinez solos at the Armory, and Shizu Saldamando solo at Art Basel. Coming into ‘24 we’re going to be showing Jerry Peña, Lorena Ocha, and Jackie Amézquita. I’m also excited by the work of Patssi Valdez, Joey Terrill, Christina Fernandez, Guadalupe Rosales, Maria Maea, Sophie Stark, and Masie Love… I can keep going.

What’s your favorite thing about going into work?

Lowkey, building a great community with artists. I love being in Chinatown. I’m thankful for every day I’m able to wake up and I thank the spirit for giving me that breath that I’m not guaranteed. I am thankful to be able to do the work, and I talk to all the elders in the community. Yeah, there’s a language barrier, I don’t really know their language; some of them don’t know mine, but we greet each other every morning. We can say hi. They come to see the shows, and I love being in the community.

This interview was originally published in our Winter 2024 Quarterly // Ozzie Juarez opens a solo show with CJG on January 20, 2024.