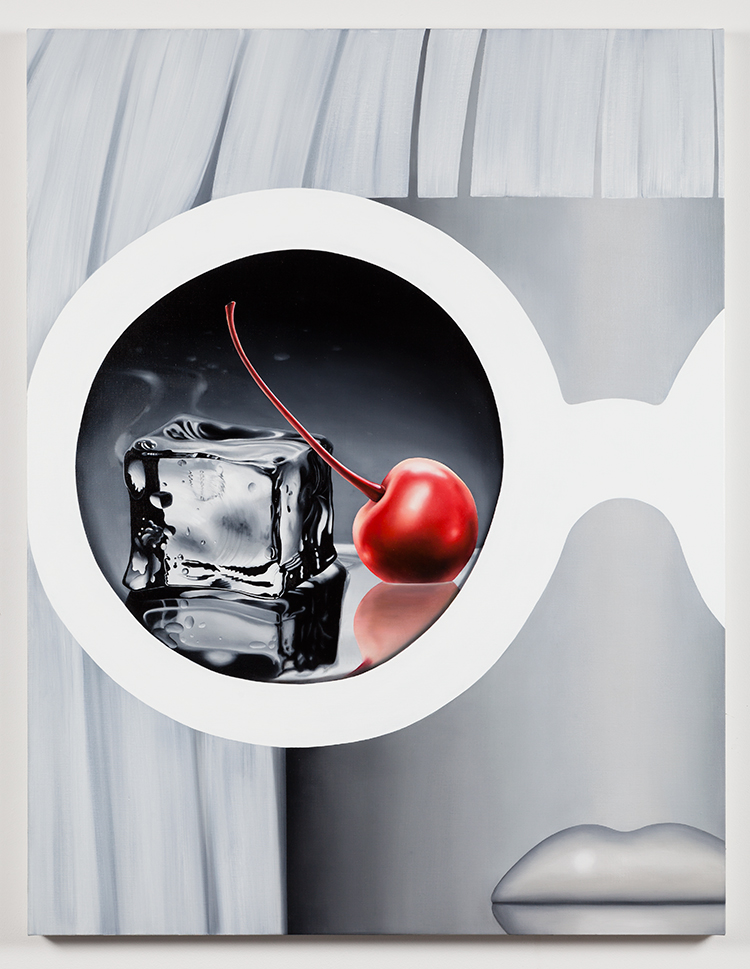

The art world loves trends. It loves definition by movement, period, format, technique and medium. From time to time, this world is stymied when someone's work just doesn't fit into any of these boxes. Texas-born Emily Mae Smith cannot be typecast, although she's been actively creating work for the last two decades. It wasn't until five years ago or so that the art gods bestowed their grace, and by the looks of her career trajectory, it looks like Smith has become one of their favorites.

We've been trying to connect for quite some time, but life kept happening and that was fortuitous. What better time to sit with Smith than at her Brooklyn studio between the opening of her first museum show at Le Consortium in Dijon, France and her exhibit at Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut? Of course, this conversation also comes on the heels of a NYC debut with Perrotin, and just prior to a Korean exhibition with the gallery. Not only is her work rich, beautiful, smart, and original, but a forthright mindset propels what she creates.

Sasha Bogojev: How does it feel to have a retrospective museum show in Europe?

Emily Mae Smith: It's a show, that through a conversation between me, the curator and my gallerist, is a collection of works from the past four years. It's about 30 paintings, and they are kind of organized by theme, but not chronological. So, in a way, it might be more like an introduction rather than a retrospective, I think.

However, it is a lot of work from my career, which is not so old. Retrospective sounds more established than I feel. I don't know why I have this feeling. I had a student contact me who said, "I'm interviewing successful women artists for my project. I really wanna talk to you," and I thought, "Why does she wanna talk to me?" So I was like, "Oh, I'm that?" I just don't really get it. I totally don't.

I can imagine it might be hard to look at yourself that way. But for what it's worth, it does kind of feel like a retrospective, because the last four years have been significant in your career.

It's funny because when I actually look at the math, I have literally been painting, like seriously, for 20 years. I'm 39, but I haven't really been necessarily having what you might call commercial or institutional or whatever kind of success until just the past four years.

Why do you think that's the case?

I think it took me that much time to grow and develop and find my voice. I think with painting it really takes a long time because it has such a history and it has so many conventions. So learning all the nuances of where to break the rules or which rules to follow, I think it just takes time.

I recently had a conversation with Camille Rose Garcia and she also talked about needing time after art school to figure out what she'd like to make.

I totally relate. I finished graduate school in 2006 when the recession happened, and it really wiped out any opportunities, because any kind of risky endeavor for a young gallery or for the marketplace was not happening. So I just felt like, "Okay, I know this is not my time. I'm just gonna do what I'm doing." I was just waiting for things to change, and make whatever change I could make. But, yeah, I remember feeling, "This is an art world that will never accept me, so it has to change a bit, and I have to keep growing. So we'll see if we meet again later." I do feel like that's what happened.

That's a very strong point of view. You were waiting for the art world to be ready for your work! Why do you think that happened and worked out?

Because I'm very stubborn, and prideful, which is not a good thing, right? But there are just some things I couldn't fake. There was a whole period of time in the past ten years in New York where if you made representational painting, it was not cool. Nobody was showing it. That was a weird micro-trend, but a very strong one. It was just all abstract. I love abstract painting like I love all painting. I love art so I don't really care, but it was so trendy. And my work is so image-based, there was just no way I was just going to suddenly become a painter of abstraction. I just couldn't do that!

But that obviously shifted...

I really went into Le Consortium completely naive, because I had never had a museum show of my work before, and I felt so awkward. I just kept pretending like it wasn't real. I didn't even do much research to find out about the history of Consortium. I'm really glad I didn't know that this was the first place where Cindy Sherman did a show in Europe. I think I would've been frozen with fear if I had known. So I stayed a little naive just to get through it. I do find that a lot of the curators in New York, curators being people whose job it is to put art in institutions (much different from the gallery world), really don't like painting or don't find it a valid medium. The curator of this show, Eric Troncy, he really seems to love and understand painting.

Any ideas of why that is?

I think it's that they need artwork that really must be explained to people, or that intervention must occur between the artwork, curator and the public. What's so radical about a painting is that it can just cut through all those layers and go directly to the person looking at it. You don't need an interpreter, you don't need a person to give the artwork therapy. Eric has curated so many interesting shows unbiased by a particular genre or medium. I was just so impressed, I thought, "Okay, here's a really good example and a really good experience."

You seem to be connecting well in Europe, right?

It's true, actually. Yeah. I keep threatening to move overseas. Do you think they'll let me bring my dog?

Definitely. We love dogs in Europe!

I'm just so very, very American, from Texas, so the idea to move to Europe sounds very romantic. I lived in France for one summer for about three months, but I was 20 years old, before the Euro. Paris was very different in '99 than it is now, like very antagonistic to Americans, and I felt really isolated. It was hard.

Well, I think Paris is antagonistic towards everything non-Parisian.

It doesn't feel like that to me now. Maybe it's the new generation. Like the Millennials, they're so open.

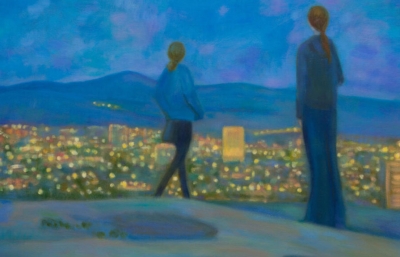

Speaking of the French, you just had a show here in New York with Genesis Belanger at Perrotin, which was a gallery move for you. How did that happen?

Genesis Belanger and I became really good friends over the past few years and kept joking about doing a two-person show. We'd go to studios with each other, and if she liked a painting in my studio she'd say, "Save that one. That's for our two-person show." When our mutual friend, Valentine Blondel, a director at Perrotin, heard us, she said, "What? Where is this two-person show? I'm really jealous." We said, "Well, we were just joking," and she's like, "No, no, let's do it. Let's do it with me." She is an organizer, I know her, and I trust her, so it's been such a super positive experience. Now, she's organizing a group show in Korea this Spring about gender norms, beauty standards, and feminism, and evidently, there's a kind of feminist awakening there. Parts of the society are so deeply patriarchal and hierarchical, so to bring that kind of work there feels really exciting.

Compared to what you've achieved so far, is this the high point in your career so far?

Yes, I think so. If it's in waves, which means things go up and things go down, this is still going up in the first wave for me. This spring, I'll have a museum show here in the US, at the Wadsworth Atheneum, in Hartford, Connecticut, which will be my first institutional show in the United States. That's what's so shocking—one in Europe, one here, back to back. It's kind of crazy.

I can imagine. What are you preparing for that one?

It's a very different show from the one in France because that was a bunch of works from the past four-plus years, curated, arranged, kind of looked at specific themes, partially retrospective. The one in Hartford was really different. Through a program they call MATRIX, they invite one contemporary artist to respond to the collection, which is encyclopedic. They have works through time, like medieval painting all the way up to contemporary. It's one of the oldest museums in the United States, sometimes considered the oldest.

What part of their collection will you be working with?

There's a quite interesting collection of American history, the history of labor, and even war, with bizarre things from the Colt gun factory in Hartford, Connecticut. The family became rich by outfitting armies and popularizing rifles, but they bought art that goes into the museum, along with all their guns, which is really wild to look at.

It kinda works for you, given your smoking gun-barrels and such, right?

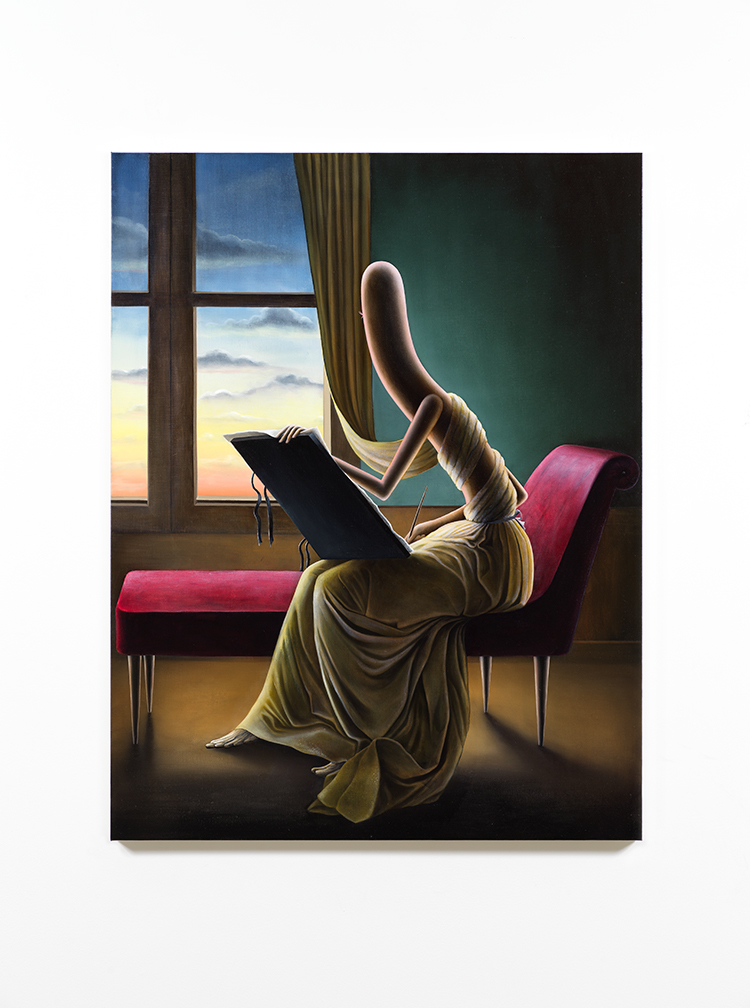

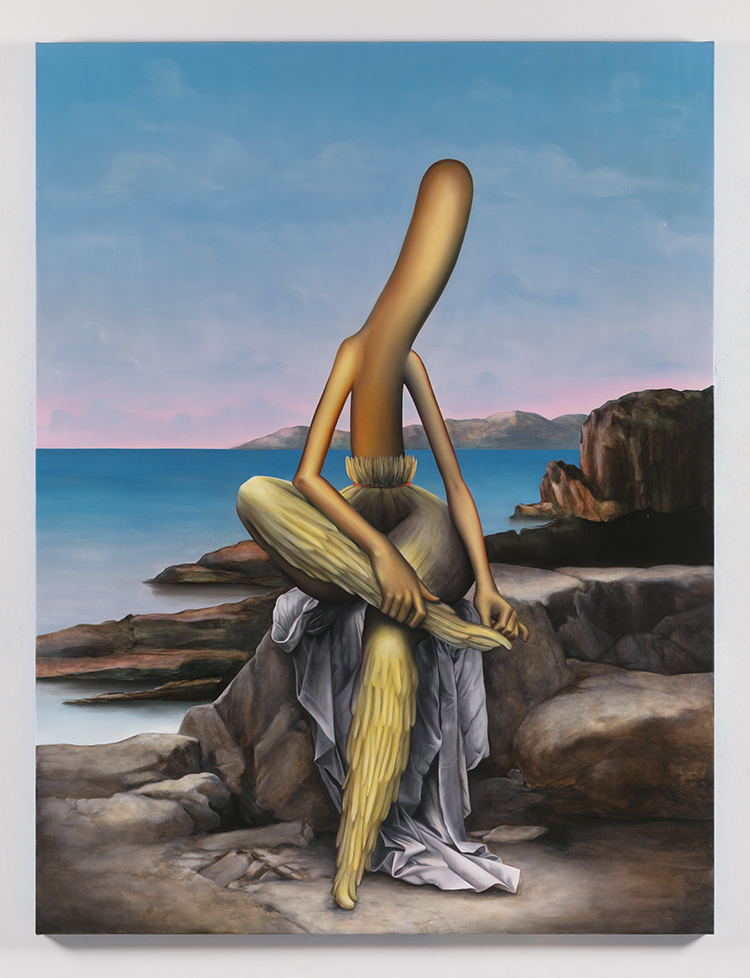

Yeah, it's just a really strange connection. But, at this museum, they also have a painting by William Holman Hunt called The Lady of Shalott, one of the most famous pre-Raphaelite paintings, from the late 1800s or early 1900s. I'm really fascinated by that period of painting, and the specific micro-movement. Hunt worked on it in waves for almost 50 years and died after finishing it. I think he went blind painting it too. It's a crazy story. It's a really wild painting because it's derived from a poem by Lord Alfred Tennyson about the mysterious Lady of Shalott, who is trapped in a tower and not allowed to look out the window at the world outside, except through a mirror which reflects the world. She weaves images of what she sees, and one day dares the sin of looking out the window instead of seeing it through the mirror and then dies. This painting is of the moment where she had just looked out the window and everything is about to change.

I'm kind of looking at it with my very subjective interpretation of my interest. I think I have a kinda feminist read or reinterpretation of the painting because it's like an incredible metaphor for the state of the Victorian woman—sort of trapped in a cycle of invisible labor, who has to experience the world through the lens of someone else. I feel so connected with this bizarre cycle that's in this painting, so I'm working on a few paintings inspired by sections of it. Through the research I've done, I think that the artist's intention wasn't any of this commentary.

He was saying, "Look what happens when you sin." Their intended message is horrific to me, but also part of the power of my obsession with them. They're so strange and upsetting, but so interestingly painted, this place where these erotic or beautiful women experience a downfall because of their mistakes, not just because of who and what they are. There is a kind of location that carries through into the twentieth century in terms of art, a way of looking at females as the image in the painting become synonymous with bad. Maybe that's part of my obsession with this time.

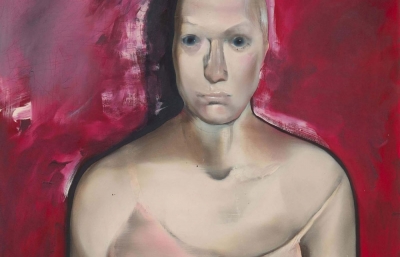

I was about to ask about the themes in your work. A lot of them are about feminism, gender roles, and women's position in modern society.

I remember being in school thinking, "Okay, I'm kind of interested in this stuff. I'm just painting the way I see things, my ideas. I'm a painter. Don't call me a feminist. I'm a painter first." Over time, I think, in my adult life, I experienced a lot of class struggle, so eventually, even though I grew up relatively privileged, I started to realize really how deeply ingrained a lot of the struggles were, and how deeply buried those things were in gender. At first, I started to address that through humor.

Humor, you mean like a caricature or something?

Yeah, because, at the time, I thought this reality is invisible to other people. If I paint it, it becomes visible. That's like how comedians work. They tell you really painful truths about the world as a joke. They make you laugh or reveal it in a way that brings you into their world rather than making you afraid, so you come at these issues with humor. I had kind of repressed that in my art, so it was like a revelation. Finally, I could paint things that were really horribly painful without feeling super self-indulgent or giving into some romantic notion of the artist as carrier of the world's pain. I could make more about states of being, conditions in society, and how they're connected to aesthetic conditions. Letting the humor come out was this big turning point, and then finding appropriate vehicles to create series helped me, too, because I could just keep digging. That's when the broom appears.

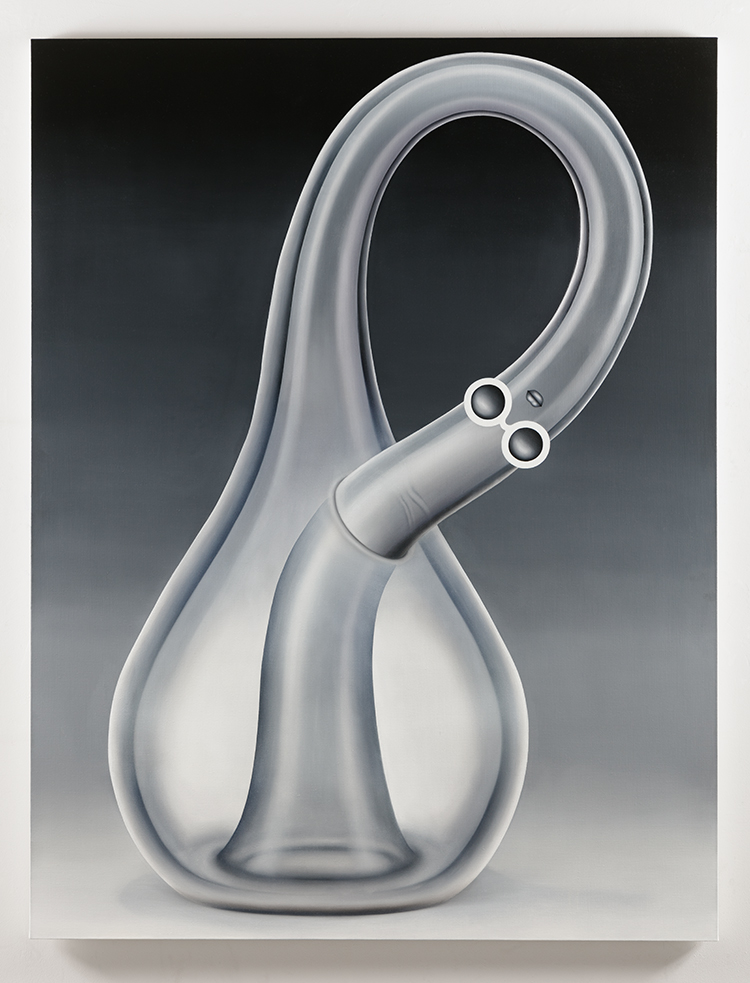

Yes, the broom. Please tell us a bit more, as it's probably your most recognized image.

Literally, a broom is a tool, but it's also this visual tool that communicates stories and ideas in my paintings. This agent, like some kind of secret agent, going through the history of art, disturbing constructs, making some trouble, or behaving badly, but is never doing the work of the broom. The broom is never sweeping! It initially came while I was re-watching Disney's Fantasia, specifically that sequence when the broom is bewitched by the sorcerer's apprentice. It was just performing the labor, completely unappreciated for doing all the hard work in making the sorcerer's castle function. I so deeply identified, not only as a female but just as a working class person. As a person who grew up working. I've had a job since I was 14, but I also went to school, so I'm very lucky to benefit from education but also be a working person. So I was like, "Oh, that broom. I'm the broom. We're all the broom. Well, some people aren't." When the broom got free, it started to do interesting things. Sometimes it looks more like a mop, sometimes it looks more like a paintbrush; and attributes of the broom become visible in other objects.

Mouth and teeth?

Yeah, this gaping mouth also goes back to the humor in trying to make invisible things visible. The mouth started as a frame, and I thought that if I put what I have to say inside of this, like, cartoonish, man-splainy kind of mouth, attention would be paid. It was a joke like if I wear a mustache, you'll think I have something more important to say. It's cruel, too. It's like a cruel, horrible joke, but I wasn't paid at the time, and it made sense to me.

Does it bother you if people gloss over all of those things? If they just see the surface?

Not really. I think joy is very radical as well. If someone can enjoy or just be stimulated in any way by looking at an artwork, I think that's a really powerful, really direct connection. I was talking with Barry Schwabsky, who is a writer and a poet, a couple weeks ago, about this very subject. He remembered this quote, "Art is the best excuse to love something for the wrong reason," or something like that. Like, yeah, even if for the wrong reason, why not?

At what point did you start sharpening your visual language?

During the recession here in New York, roughly 2008 and 2013, it was really hard, and I had to go from one weird job to another, working for artists, or working for galleries. I drew illustrations for a children's cookbook, all these random things just to get by. I was teaching, also, which I like. I got kicked out of the building where my studio was, and I suddenly found myself in my thirties, very limited. It was really painful for me because I had been so privileged to have a studio my whole adult life, one in school, and one immediately after school. It was the thing that I spent my money on, to have a studio, a place to make my work. I actually had felt ashamed because, I thought, lots of people don't have a studio. And it was a shock. So then I was just working on a tabletop in our living room and was forced to make really small paintings that I really hadn't been doing before. I had to use different materials because I was painting in my house, and oil paint is toxic. You have to use mineral spirits and so on, and I really couldn't have that stuff in my house, so, I had to make small paintings with watercolor, acrylic, things that were water-based. My work became more simple and more hard-edged because of this. Also, because oil paint is so soft and fuzzy, you cannot commit. You can kind of just softly approach an idea, not really have to put something down that you can't take away. This really forced me to just be very clear with myself as to what were my intentions with these paintings and forced me to make them communicate very simply. So it was an art of reduction when I started doing the mouth and the broom. That was about mid to late 2013. It sounds kind of corny, but I had to lose everything, my studio, my materials, everything I was comfortable with…

Emily Mae Smith's MATRIX 181 was on view at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut through May 5, 2019. This article was originally published in the Spring 2019 print issue.