A curious aspect of feeling out of place is that it’s universal. Everyone, at some point, has felt peculiar, abnormal, different from the rest. And while these abnormalities may make us feel self conscious, at times ostracized, they’re often also what make us the most powerful, the most loveable.

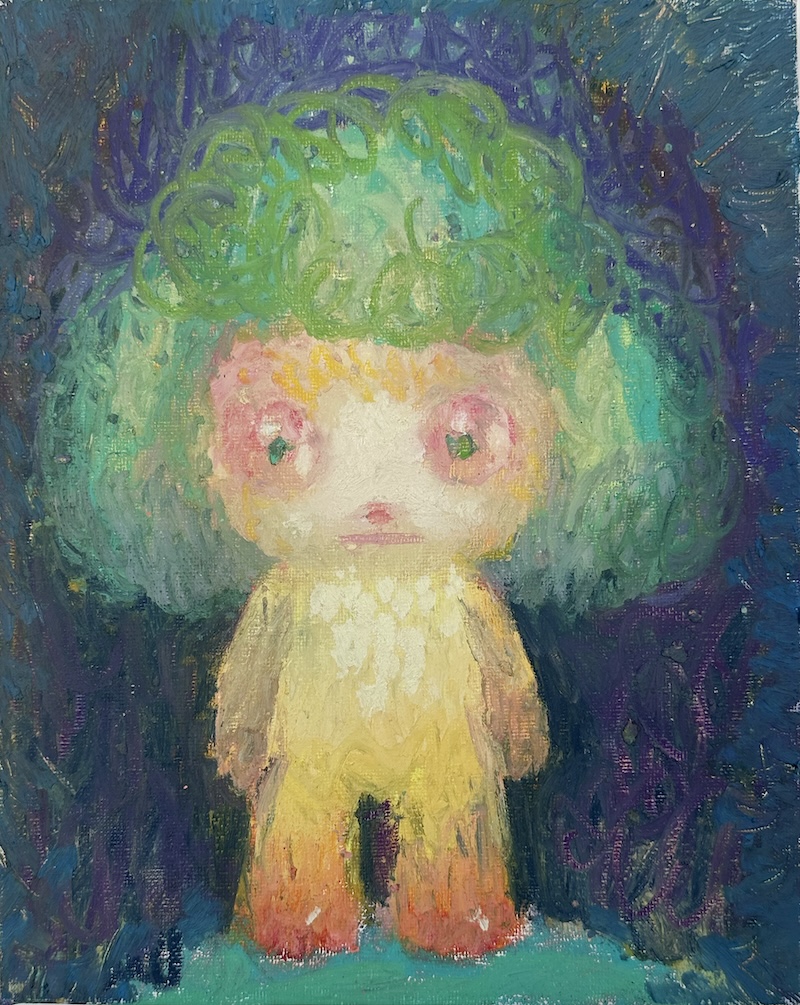

So Youn Lee’s latest solo exhibition at Hashimoto Contemporary, Anomaly, explores the journey of feeling different and finding belonging within circumstances that are themselves strange. Her main characters Choco and Mango navigate a world of anomalous creatures discovering themselves and their extraordinary surroundings, imagining a place where those deemed peculiar or offbeat naturally find a home. Before her solo exhibition opened at the Los Angeles gallery, the artist spoke with Katherine Hamilton about these characters’ developing narrative arcs, how a great loss inspired new changes in her artwork, and how she’s continuing to eschew stylistic labels.

Katherine Hamilton: Mango has been the protagonist of your paintings for a while now, adventuring through space with your dog Choco. What do you feel like Mango has learned over these years? What have you learned from them?

So Youn Lee: It’s a very fun question. I think Mango has learned to love Choco even more. They’ve been on so many adventures together, comforting each other and being there for one another. I consider their story a space opera with coming-of-age elements. Mango has learned that they can be anything and everything, as long as they stay curious and are willing to change.

I've learned patience through art making, and expressing myself and ideas with many different mediums compared to the beginning of my journey with Mango and Choco. It started with pen drawings in 2013, now I create paintings, sculptures, digital paintings, and even 3D art of them. I still consider human beings as aliens and voyagers who stay on Earth for a given time and then leave; there’s more in the universe than our physical world, and I would like to express these ideas with Mango and Choco through my work.

You often blend textures: figures might appear smooth, their skin like a cloud, but explosions or sun rays behind them are rendered in bright colors with rough, gritty textures. What draws you to blend not only saturated and pastel versions of colors, but various textures on the canvas?

Mixing textures definitely gives the painting surface more character, and the contrast makes the figures evoke more eerie feelings compared to the surroundings. I like the way figures and the ground become ambiguous, both in contrast and textures. The chaotic stimuli is a visual interpretation of how my brain works, seamlessly moving from one thought to another. It’s quite amusing when I observe it. One of the things that I really enjoy about working on canvas is its physicality, compared to digital media. Creating a physical work feels like I’m giving a body to a ghost or idea.

This exhibition with Hashimoto Contemporary, Anomaly, seems to be a different thematic approach. Where adventure, optimism, or innocence may have been central themes in previous works, you’re introducing new or expanded themes of finding acceptance and belonging. Do you feel like you’re venturing into new subject matter?

From my perspective, these themes are interconnected. As I mentioned above, I see the world of Mango as a space opera with coming-of-age elements, which are evolving and growing. The adventure is about finding one’s true self, and to do that, one needs to stay optimistic, experiencing and trying out new things. Only then, they learn about acceptance and belonging for their surroundings and themselves. The sense of belonging is something that many people in our society seek every day, yet it always starts with understanding who they are and being comfortable with it. Innocence still permeates the artistic mood of my works; I strive to be as genuine as possible at every step of the work in progress.

How do you find belonging?

I’ve always felt like I’m a bit off-beat, which is fun when you’re an artist. I think every artist might feel like they are a bit weird because we are very sensitive by nature.

I found my belonging through making and sharing art. I know it sounds so predictable, but it’s true. I feel connected when someone feels, sees, or perceives my work. It doesn’t necessarily have to be positive feedback, but the interaction itself makes me realize that I exist. Especially with today’s hyper-connected internet culture, when people look at my artwork and find connections, feelings, and interpretations that resonate with their own experiences, I feel connected to the world. I also feel a desire to connect with countless photos, writings, and stories on the internet that inspire me, seeking connections with them and the people behind them.

You mentioned that this series of works in Anomaly is the final of a three-part introspective series. What has challenged you these past couple of years?

Yes, the three-part body of work started in late 2022. In June 2022, my dog Choco passed away. He was the inspiration behind the character Choco in my works, and he gave me the chance to observe the purity of animals, which extends to nature. I learned a lot from him.

Before his passing, the world of Mango was about facing challenges and focusing on the bright side, and against dark forces of life such as death, sorrow, and despair. I wanted to create a world that was safe and perfect. However, after having to let go of him, I learned to mourn and live with grief. But that helped me to accept the duality of everything: good and bad, happiness and sorrow, life and death on a more personal level. I still miss him; he was the best—yet I’ve been even more inspired by him these past two years.

How did this enormous life change affect your practice?

The change triggered a genesis—Mango’s new world. In the new concept, Choco passed away and entered into limbo. Mango followed him, but Choco didn’t remember his best friend. They needed to rebuild their bond and become friends again. I wanted to tell Choco’s real story to extend his existence beyond reality. I painted a very still and silent world, foggy and mysterious. I used a slightly darker color palette compared to my previous works, as the world was in a perpetual dawn-like state, marking the very beginning. I showcased this body of work, In Limbo, in Hong Kong in April 2023.

Following the body of work, I started Solace, which was shown in Seoul in August 2023. It focused on sleep, particularly the feeling of comfort experienced when falling asleep. During sleep, one can forget all their problems and worries, feeling refreshed upon awakening. In Greek mythology, the gods of sleep (Somnus) and death (Thanatos) are twins. In their culture, it is believed that death is akin to a long sleep. I found this idea appealing, as it seems to make the loss of a loved one more acceptable, as well as the concept of one’s own passing. It gave me a sense of relief. I painted Mango and Choco sleeping together, their eyes closed for the first time, mimicking this twinness between sleep and death.

The second part of the series, Lonely Hearts, was shown in London in February of 2024. This body of work explored and expressed the yearning for genuine connection and communication in our contemporary lives. I integrated emojis into my works for the first time to establish connections with the viewers and to express the idea that we are fully emotional creatures behind our online profiles or phone screens. I used lots of blues and greens for that exhibition to evoke a melancholic feeling and to convey the idea of the sweetness of being alone and the underlying loneliness. I also introduce Mango in that show inspired by the cloud emoji, Cumulonimbus. It will appear again in Anomaly in a different context.

You’ve mentioned that artists like Aya Takano or Yoshitomo Nara are some of your biggest influences. Their figures have these soft, round edges that make them seem innocent, but there are elements of danger—they can fight back. Do you feel like Mango and Choco have secret weapons?

Yoshitomo Nara is definitely my favorite artist of all time. I would say Mango and Choco’s secret weapon is their curiosity and open-mindedness, especially against prejudices. I built their world as a benign place filled with potential and possibilities. I want them to be free to be anyone and anything. I want them to fight back by being themselves. Sometimes silent stares are all you need.

There seems to be particular rules in the world you build. Are there any sources of fiction or sci-fi you have drawn from to create these narrative rules in your works, and how they relate to the world around us?

I am a big fan of sci-fi movies and comic books, so I draw inspiration from many different references. I like the idea of communication between different species. It makes me wonder if we are the only ones in the universe or if anyone else is out there. In the beginning, Choco wore a space helmet, and in some paintings, both Choco and Mango are shown wearing helmets. I used the space helmet as a symbol for respecting each other's boundaries and understanding that they are from different worlds (with different cultures, beliefs, languages), but now that motif rarely appears in my work. Instead, Mango has become more abstract and fluid in terms of their appearance and how they blend into the environment. I think we've learned to co-exist in a better way, at least in my work. It's like transformers in sci-fi movies, where some evolve into new species in the new environment over time with the original dwellers. Both sides are affected by the changes.

Something you mentioned when providing some context for the show was the influence of filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky, particularly his statement that “there is no difference between dreams and reality.” Can you say more about where the reality of your works are located, and how dreams factor into your making?

To me, what he meant is more like we are living in our own version of illusion. For instance, I gathered inspiration for this body of work from interesting images of natural phenomena, unusual animals, and funky fruits, recreating them in my own version of illusion. Then, I present them in the real world so we can see them together. Once it was a subjective and personal idea in my head; now it has become an objective thing in the world. So, in that sense, I create a new addition to the world through illusion and live inside it.

There was a time when you spoke about your work as “cute Surrealism.” I feel like this description is still fairly accurate—the figures have these wide eyes and pursed lips, rendered in this hazy soft colors, but there’s also an element of strangeness or surprise—I’m thinking about the seal on a rock in Awake or the animated watermelon in Watermelon Juice. Were you thinking explicitly about Surrealist influence when finding your style, or were these moments of peculiarity fairly natural for you?

I would say it’s more on the natural side. I love Surrealist paintings, but I draw inspiration from many other things. I consider myself more like an outsider artist nowadays, since it’s hard to find a label that really fits what I do. Though I have an art background, my training wasn’t in fine art. My painting techniques are mostly self-taught, as are my sculpting skills. I didn’t have a fixed agenda to pursue an “'-ism,” and I like my work for what it is. I don’t want to be labeled yet.

Anomaly is on view at Hashimoto Contemporary Los Angeles through July 6th. Installation and opening night photos by Megan Cerminaro.