Sitting down to interview Dave Eggers seems like a test of focus. There are the countless books and stories he has written, including his newest novel, "Heroes of the Frontier," which I am happy to acknowledge, though we never got around to discussing it.

There is A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, The Circle, A Hologram For the King, and You Shall Know Our Velocity, all of which I devoured as each was published. He conceived the influential McSweeney’s publishing powerhouse and the incredibly smart quarterly The Believer, and of course, spearheaded numerous tutoring and learning centers that he founded under the 826 National name. Not to mention, he has written major screenplays like Where the Wild Things Are. This just means there’s a lot we won’t get around to talking about.

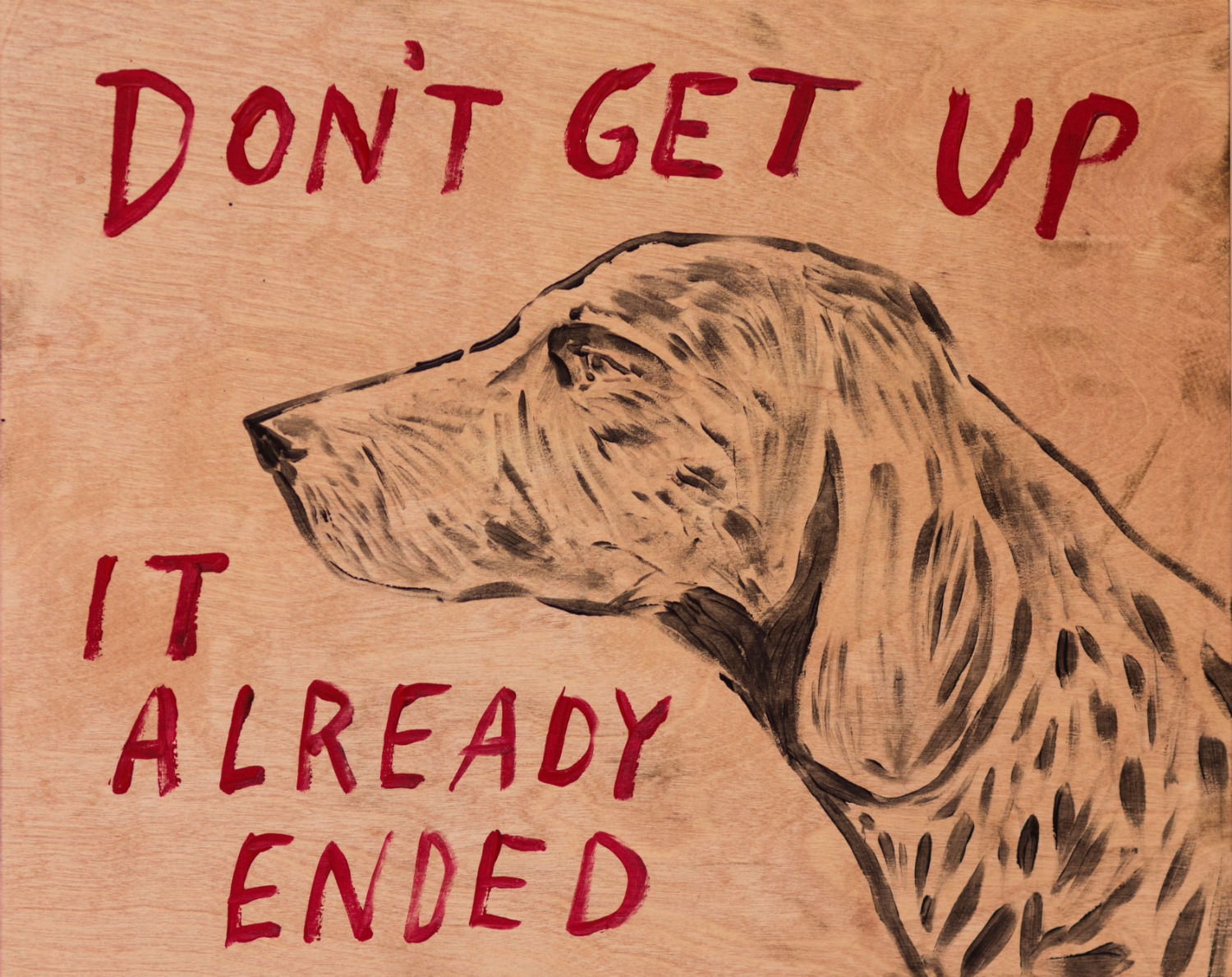

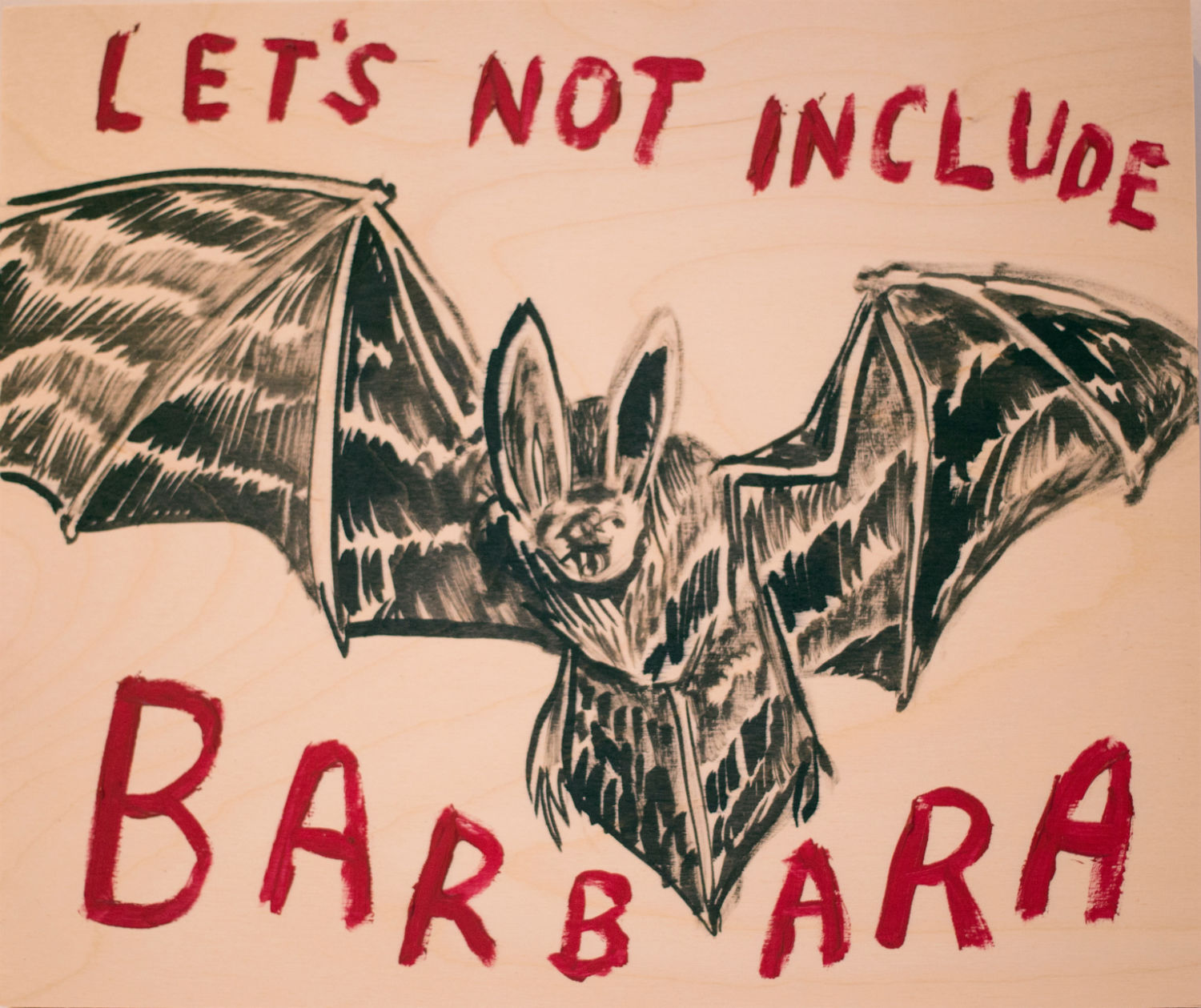

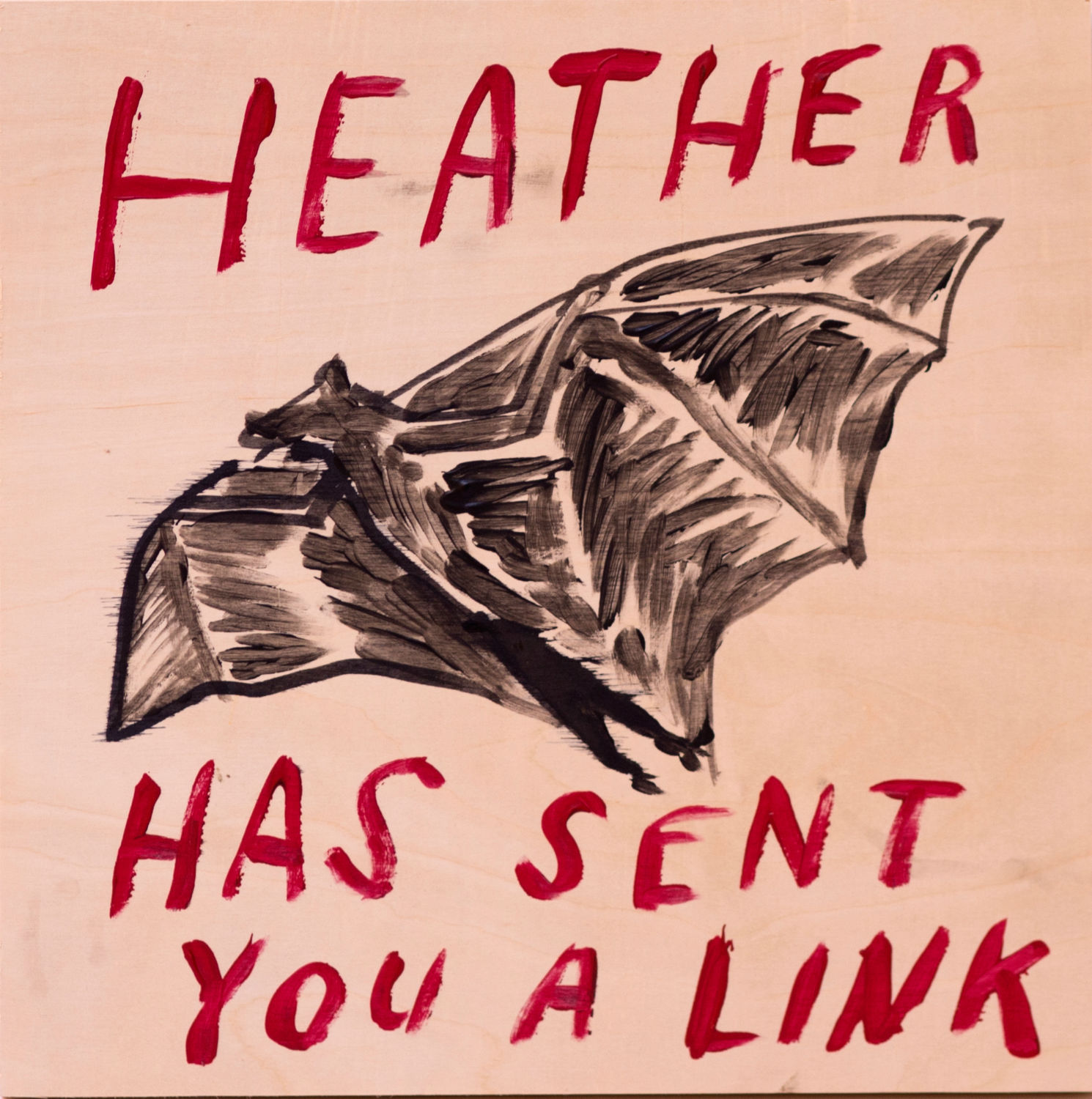

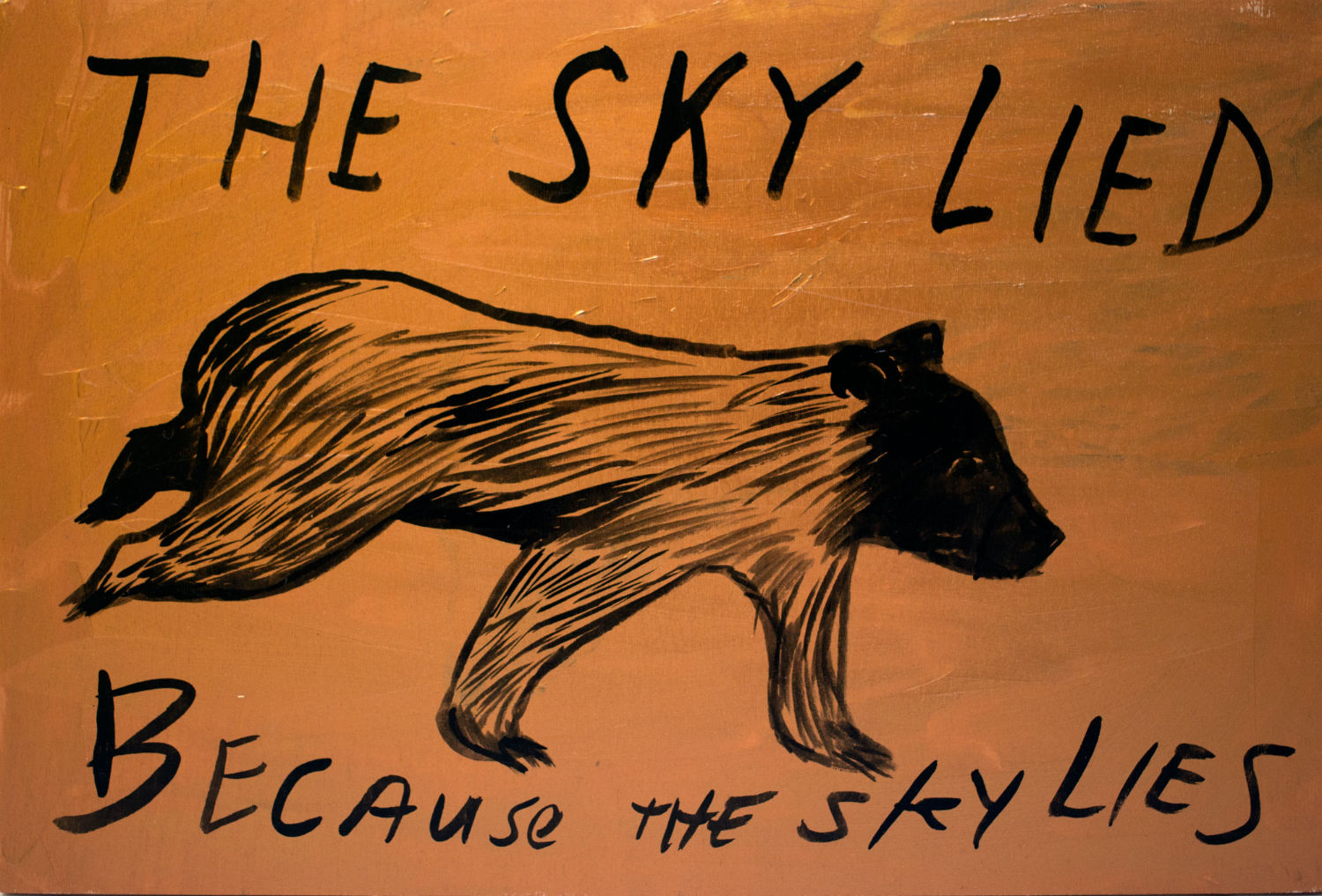

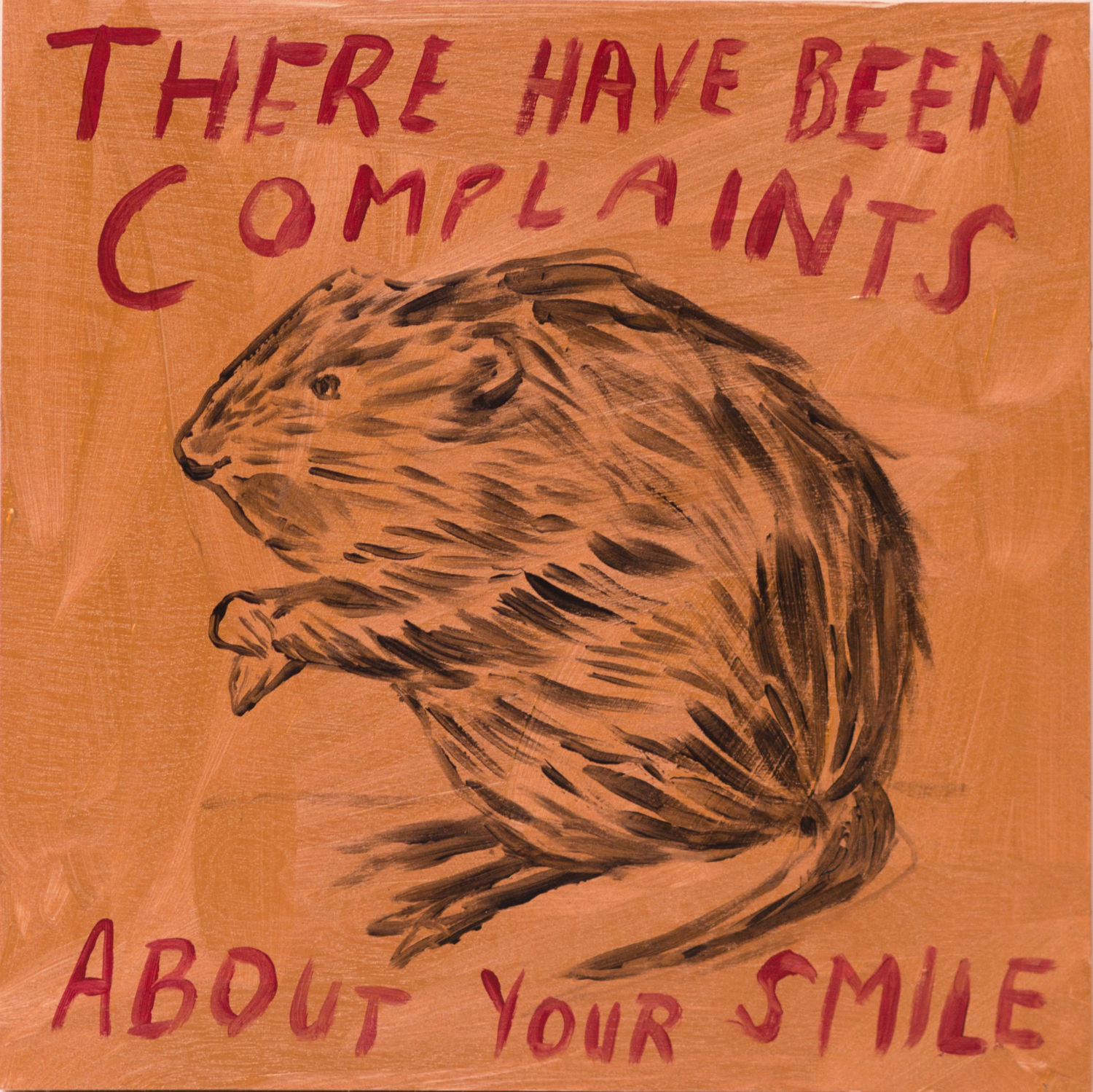

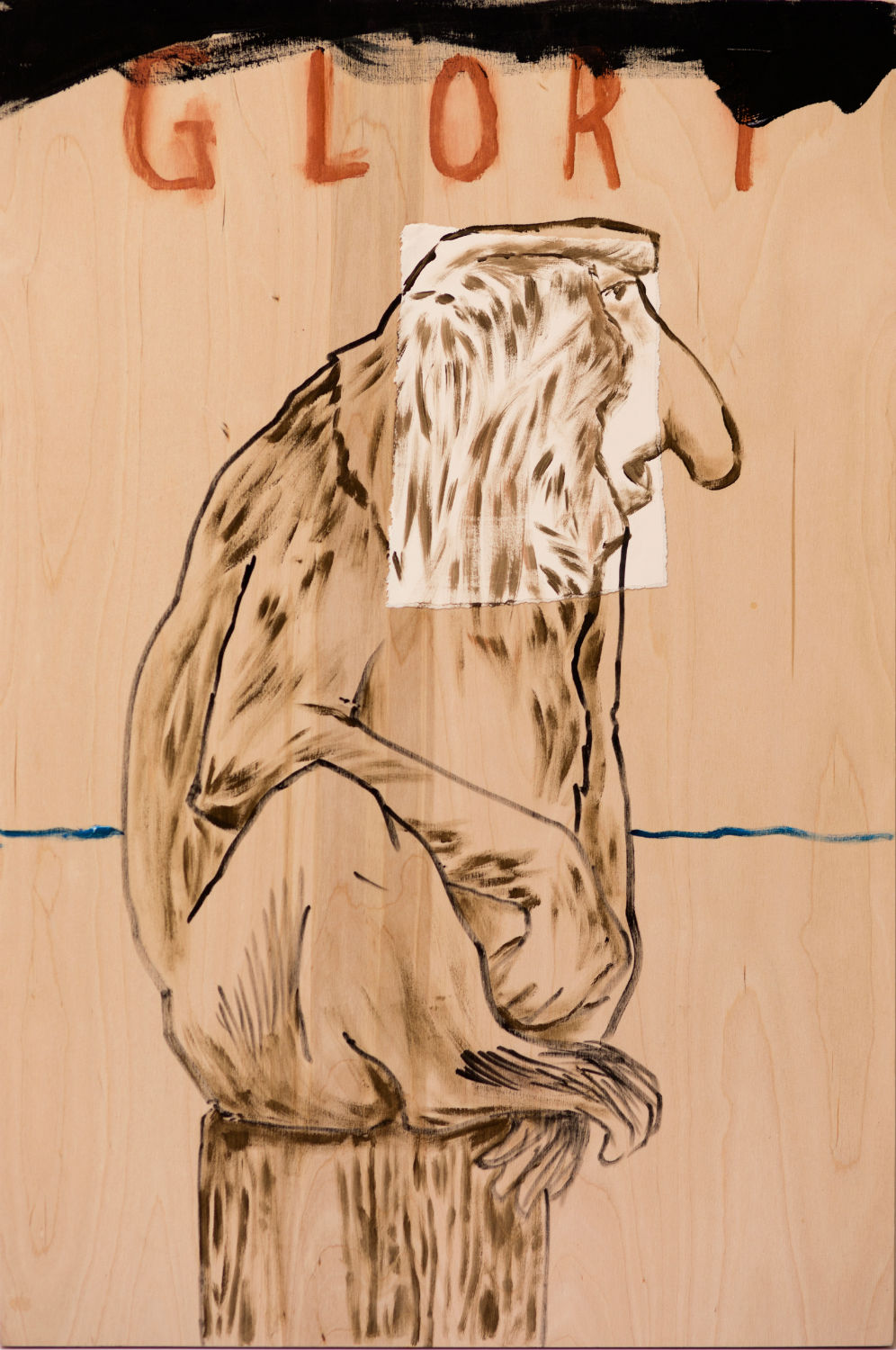

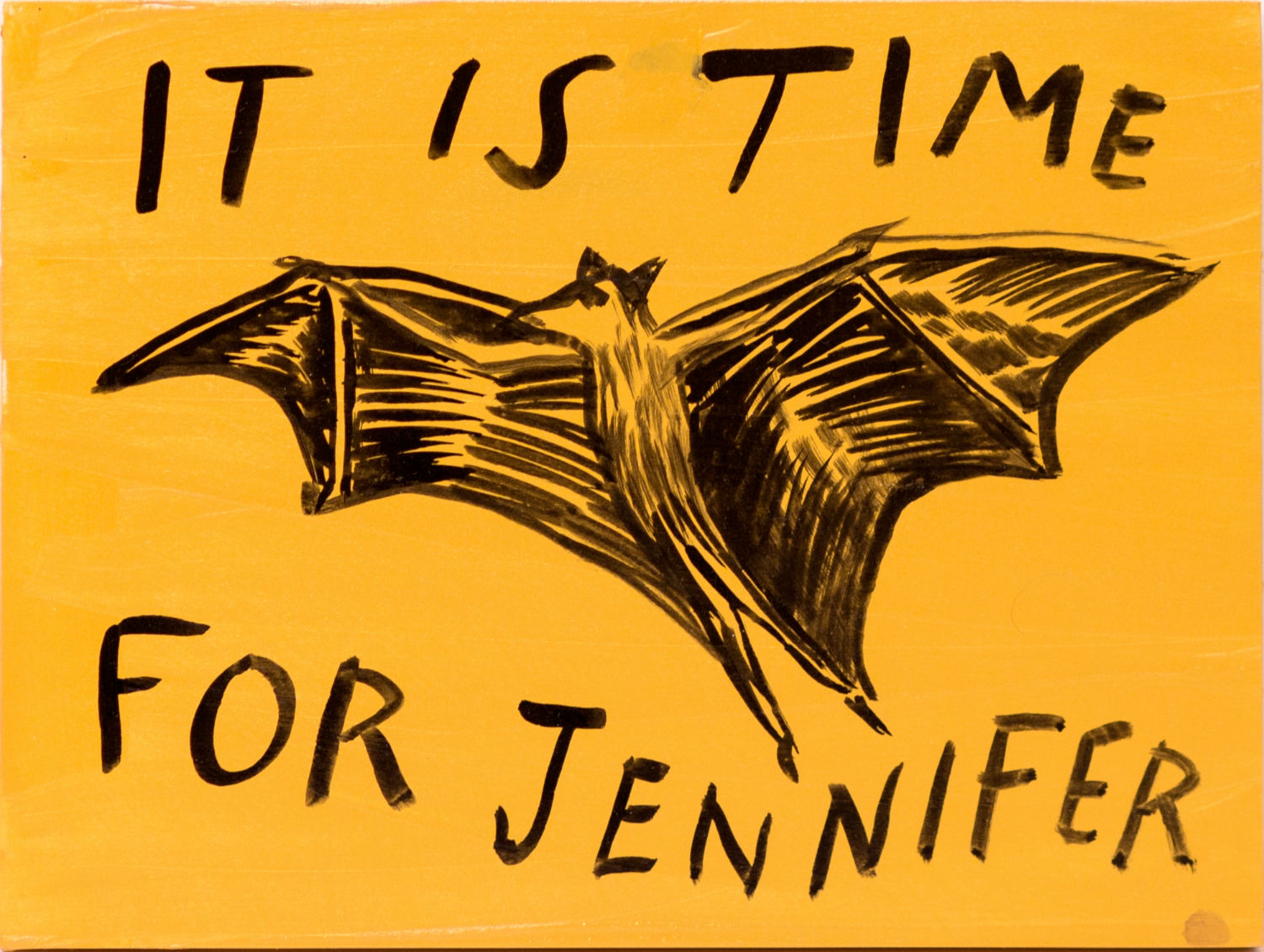

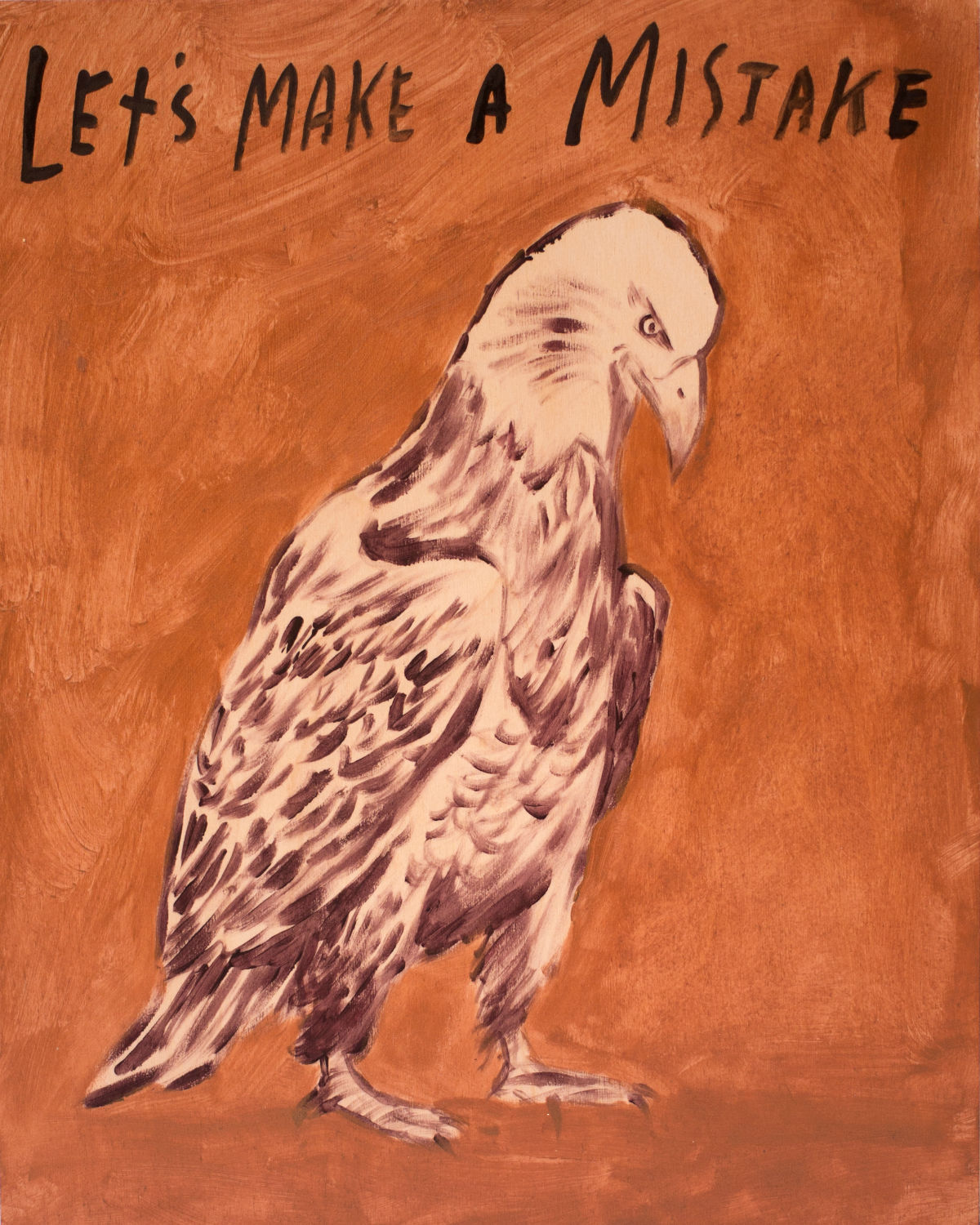

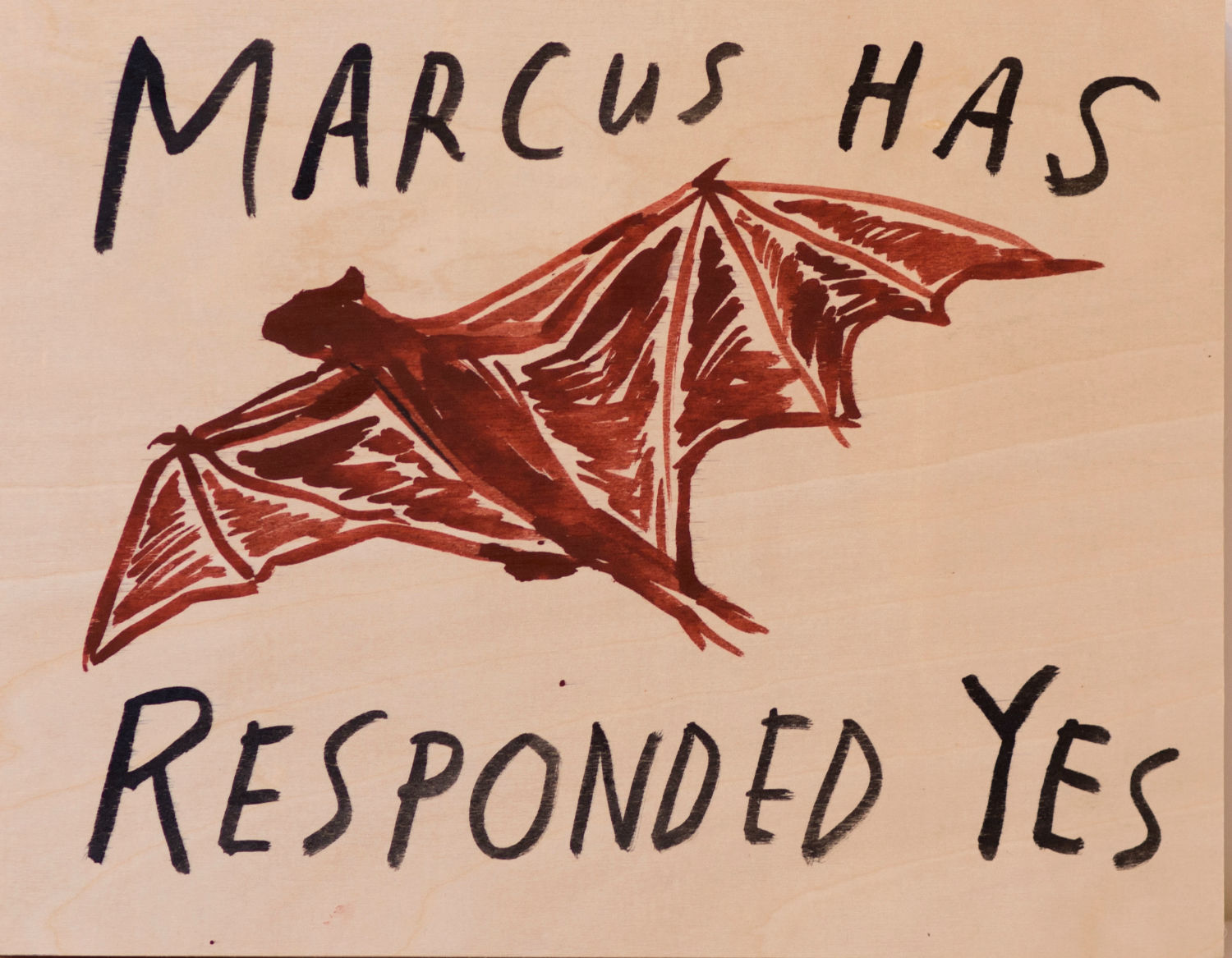

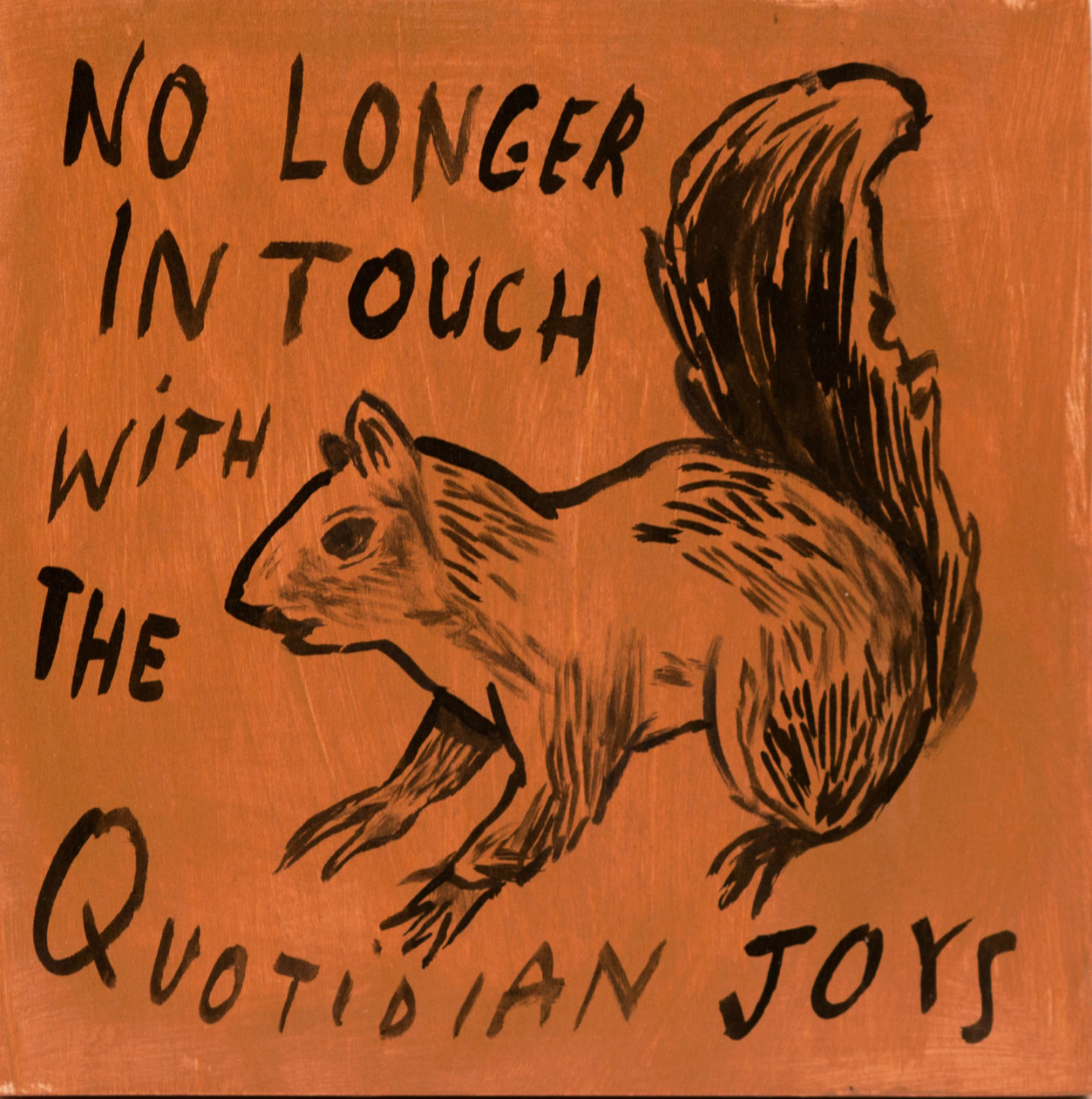

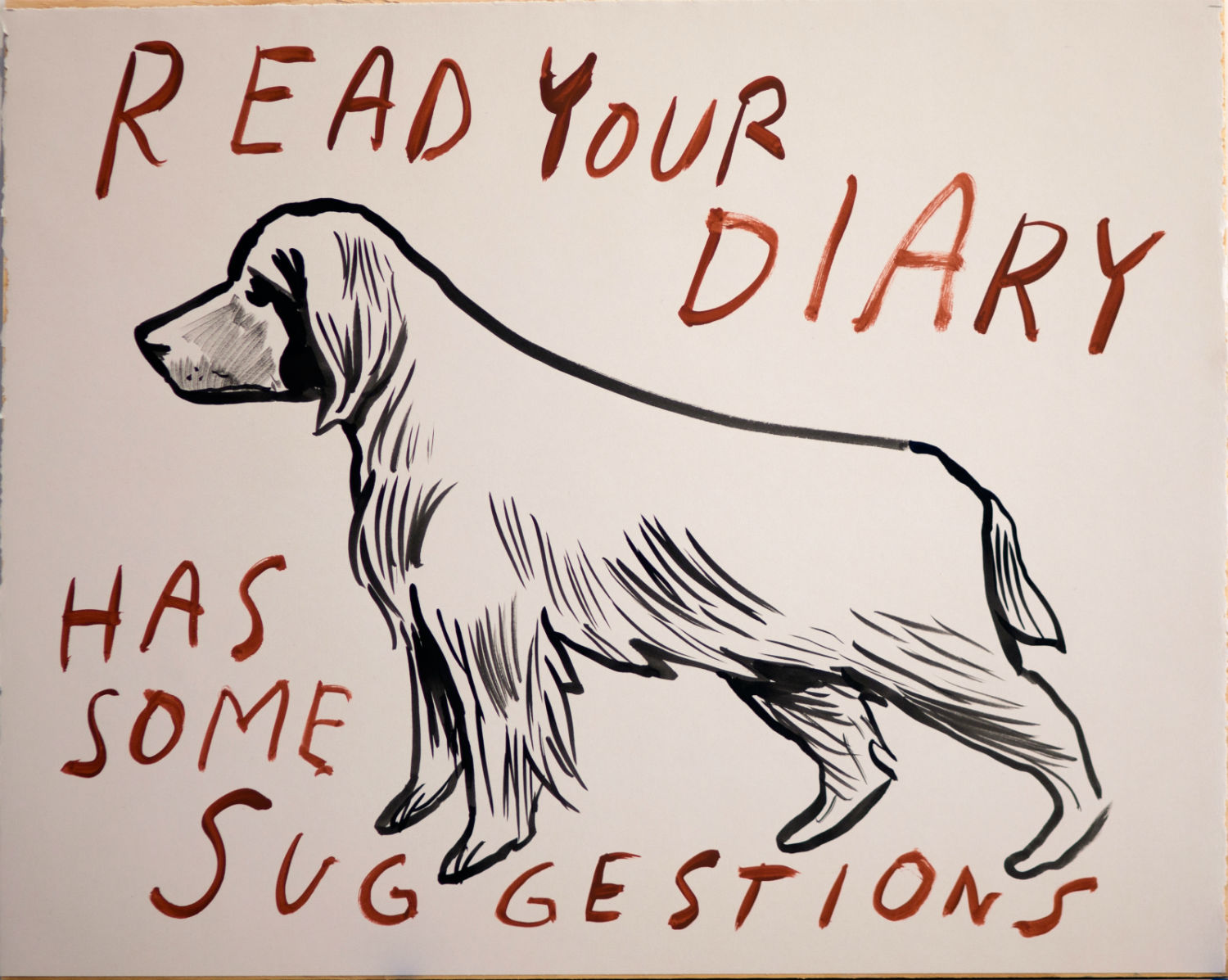

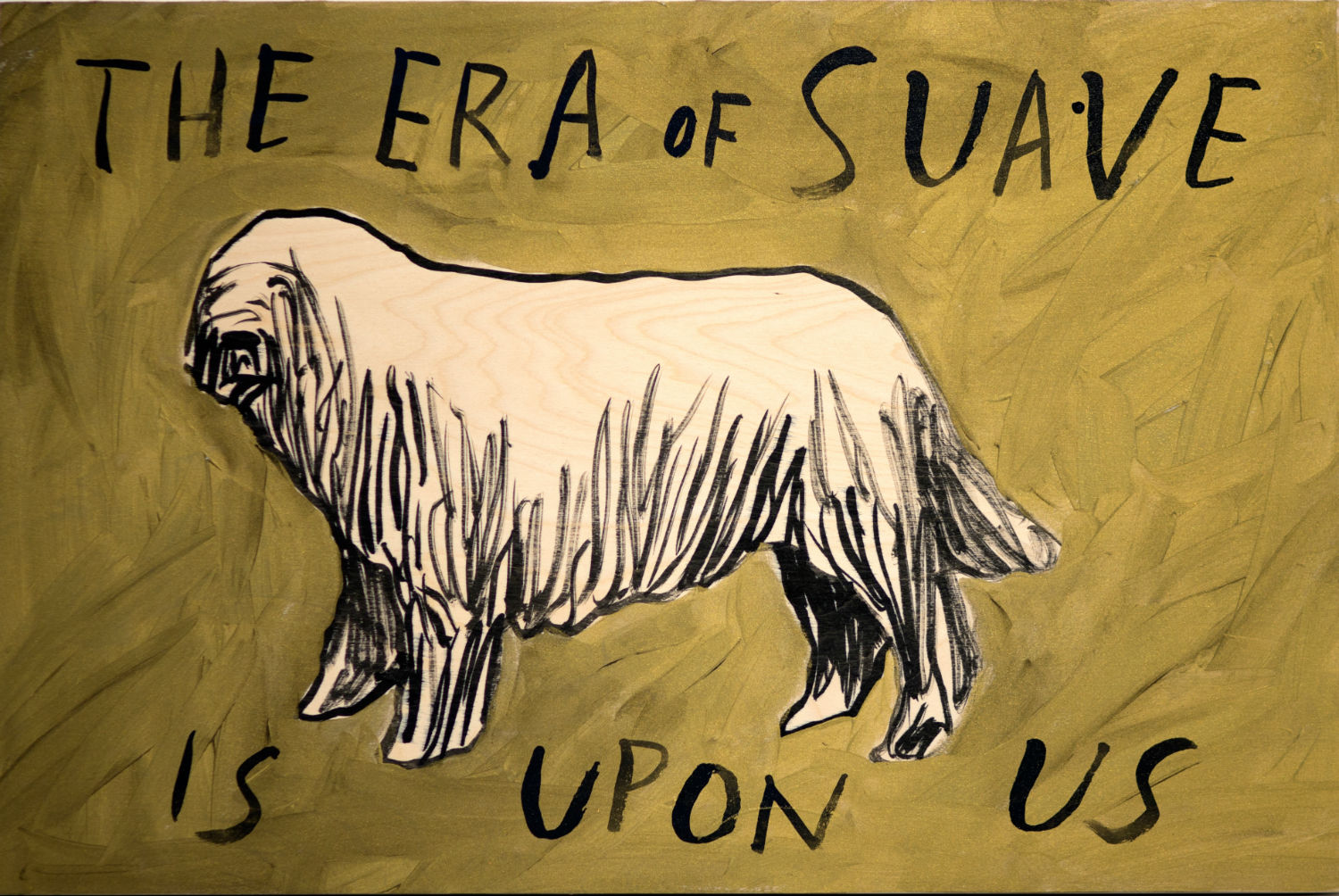

Dave Eggers is an artist. And not just the happy-accident-because-I’m-a-successful-author type of artist. Dave studied art, worked and curated in galleries, art directed magazines and books, and is a visual artist whose work shows up in fairs around the country. His career in fine art took off in 2010 at Electric Works in San Francisco with a solo show that contained the now iconic and quirky, humorous, almost existential portraits of animals and house pets accompanied by sayings and biblical proclamations fit for a highly literate Twitter universe. Consider a morose ox with the words “Let’s Get this Party Started” floating around its head, or a mouse commenting, “I have talked to the flowers. I find them pushy and superficial.” You stop and laugh, and then conclude, “Well, why wouldn’t the mice think that? Who am I to know what the ox really feels right now?”

I bring some of this up to Eggers as we sit at his new tutoring center, 826TLC, in downtown San Francisco, on a warm summer afternoon. We talked about his admiration for Robert Williams as rebellious draftsmen, his work one summer in a blue chip gallery in Chicago, and how his McSweeney’s titles pioneered connecting contemporary literature with the likes of Chris Ware, Marcel Dzama and other heavyweights of the art world. But mostly, we talked about how art shaped his life, and how regardless of where being a best-selling author takes him, there is a still a studio in his garage where he can paint.

Read the full feature in the September 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine.

Evan Pricco: This is a funny antecedent to the interview, but did you know I was an intern at The Believer in 2005, right before I started at Juxtapoz? I was probably the worst intern you guys ever had.

Dave Eggers: Yeah, we have a monument... it must have been you. But then you took over Juxtapoz, so you couldn’t have been that bad.

I just wasn't good as an intern. But I remember wanting to work there because McSweeney’s and The Believer were really one of the first publishers to help bring those worlds of art and literature together. You guys had Chris Ware doing a McSweeney's quarterly and books with Marcel Dzama. That was a really nice kickstart for how art and artists have become so integral in twenty-first century culture.

The Believer was conceived before we had one word inside. Charles Burns was hired before we had a magazine yet. I did a sketch on a piece of paper, a tic-tac-toe board, basically, a grid of nine boxes, and I thought, “You want faces on the cover of the people inside, but what if it was illustrated?” Charles Burns is one of the great stylists of all time with such a muscular style that can hold up on coated stock and any kind of printing technique. The ink is so heavy. I wanted it to be able to compete at 50 feet away from other titles. So we asked if he would do some covers, and I mocked it up with some of his old portraits. Luckily, he said yes. He joked always about how many portraits he'd done, and how maybe the work was mind-numbing at a certain point. But we were always trying to give work to illustrators and comics artists because that's where I'd come from. I was a cartoonist for SF Weekly for a lot of years and so I got to appreciate just how hard it is to do it well.

But when it comes to the special McSweeney’s packaging, or The Believer, you want to be able to ask Chris Ware, or Tony Millionaire, or Burns, “Hey, would this be fun for you? Do you want work like this? If not, don't worry about it, but we're here. We'll run you anytime you want.”

Was it a way for you to connect with people that you liked?

Yeah! But that's why you start magazines, right? With Might magazine way back when, we had an entree to reach out to David Sedaris in 1994, right after Barrel Fever had come out, and say “You wanna write something?” We had the entree to say hello to Rick Moody, David Foster Wallace, people that were only six, seven years older than us, but we loved their work, and maybe could run something that they had sitting around in a desk drawer. So a magazine is a way to curate a group of people you admire, do something together with your friends to create a mini-curated world of taste.

You guys kind of turned it into an art piece, too.

McSweeney's? Yeah, it has that element. Because with Might magazine we tried to be good designers and sometimes we were. With McSweeney's, we would do everything. I had worked in glossy magazines for a while, and I just thought, I'm gonna put every constraint possible on the basics. One font, uncoated stock. And work within that and make it a little more pure. And then the art major in me, I guess, was like “Well, what if every issue was unique?” And at that point, it was being printed in Reykjavík, so I would go out to Reykjavík, walk the floor...

Wait, hold up, why Reykjavík?

So, this is a good story. I was living in New York and walking around the galleries in Chelsea, and I wandered into some gallery. I can't remember which one. And it was a show by this guy named Peter Garfield, who was a photographer, and I bought the catalog and I was looking at the pictures in it, which were these homes flying through the sky. In the catalog, it explains how he would pick up prefab homes, like with an industrial crane, a helicopter, lift them up 2000 feet in the sky, drop them to the earth and take pictures of them while they're flying through the atmosphere. I tried to get in touch with him. I wanted to write something about it. I love that heroic scale of these artists like Christo who would do things on that level. He had me out to his studio in Williamsburg and as we were walking around, I said, “I love what you're doing. I can't believe the scale you're working in, and it must be so incredibly complicated to hire a helicopter and hook that up.” In the catalog, seriously, there are photos where he's got a crew with hard hats.

He said, “You're kidding, right?” I said, “What do you mean? Those weren’t real houses, and that catalog wasn't a real catalog?” He then picks up a model from his table, and all the images were these little tiny models, like train houses from a model train set. He said, “I just throw them in the backyard, I take a picture.” But I'd been duped and really happy to have been because it was genius how he had created an alternative universe of how he made his art. In the catalog, there was a fake interview with an Italian curator, there were fake pictures of him with his crew, fake helicopter, everything. But one thing that really made me think was that the catalog was printed in Iceland. I thought, that's weird, they can't print in Iceland, there's no trees in Iceland, there's no pulp in Iceland.

"Bear Pedicab," Kinetic Sculpture (2016)

There's around 300,000 people in Iceland, you would not think that book printing would be a priority as much as say, dentist or plumber.

I found their rep in New Jersey, told them I was thinking about printing a quarterly journal, to give me an estimate; and he gave me one that was really competitive, and I'd always wanted to go to Iceland. It gave me an excuse to go back every three months, so I spent a lot of time in Iceland. But every time I was on the floor, I would see some other book that they'd done. They printed all the bibles in Iceland. So, I would say, “Well, how much does it cost to do this? Like foil stamping, how much does it cost to do that ribbon marker? How much does it cost to do a three piece cloth package with a tip in and die cut.” Well, it would be, “That's two cents, that's ten cents.” All of these techniques I hadn't seen in years, and rarely seen applied to regular books.

But all together, the guys on the press and those of us in Brooklyn, would come with a lot of ideas. And we had a blast, inventing new forms and saying,”What if there were 4 different covers for a 5,000 unit run?” I learned so much on the job with experimenting and having a printing partner who tells you, “We can do this, we can do that.” The guys on the press are excited to have something unusual. We got ourselves in a spot where we actually did need to reinvent every time because our subscribers expected it. We would just sit there and think about how we had an issue that was going to be bound in glass; then it was plexiglass, then that didn't work. An issue that was held together with magnets. I do think we have hit a Renaissance moment in the last ten years; there's been a lot of publishers, because of the rise of e-books, they've had to fight harder and make the object more beautiful and more want-able and unusual.

Portrait by Ramin Talaie

I think it’s that “collectible” part of publishing that may never go away.

Then you've had this corresponding rise in attention paid to graphic design, typography. As with magazines, it's the same thing. When you see a magazine read and recycled after a day or two... these things are hard to make, as you know. There's nothing sadder than when you have two months of sleepless nights of putting a magazine together and it's deemed not worth keeping, the object isn't worth keeping! I've seen stacks of Believers in people’s houses because they feel like it's perfect bound, it's nice looking, it would be unfair to recycle it…

For your art, and I mean Dave, the fine artist, not the author or publisher, when you were studying art in school, did you feel that you hit a point where you thought you couldn’t paint as a profession?

When I was young, I was sent around to have extra enrichment training, because when I was seven or eight, some teacher said, “This kid knows how to draw.” I was sent to the Japanese watercolorist who lived down the street for private lessons, and then I was sent to the somebody who would teach me drafting, then I would go down to the Art Institute of Chicago as a teenager to take night classes.

Did you like all these courses?

Yeah! It's all I wanted to do, all I did all day is draw. I would do other schoolwork and writing because I had to, but I would keep drawing. I went to college as an English major but I knew I was going to study painting. I was a painting major for two years but was lazy as all hell, and I was around a lot of wayward peers; nobody knew what they were doing. It was the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, it wasn't like the place for... we weren't at Parson's or anywhere near that. It was no fault of the school because they had a good art museum and a real program.

I really find it hard to believe you were lazy.

I was doing other stuff. I ended up working for the school paper and was a cartoonist for them, and a photographer and designer. I loved that. And I'd go to my studio and hack something out that was very mediocre, but enough to get away with, I guess. At a certain point there was a professor who said, "What are you doing? You gotta get serious. You’re gonna have to get a portfolio together so you can get your MFA." What's an MFA? I had no idea, I'd never heard this before. I have to do two or three more years of painting? I couldn't be in school three more years, I wasn’t gonna do that. And at the same time, I was like a lot of arts students of that era, with this real conflict between those of us that wanted to do figurative, representational, maybe even narrative art, and the professors at that time who were mostly Abstract Expressionists.

And with that, a painting MFA, sometimes your only career path is gallery representation, which is fascinating but really hard to do. Whereas in getting some figurative chops, illustration and design, for example, there are options for you that are a little more approachable.

Exactly. When I was twenty and still a student, I interned at a gallery in Chicago in the River North area. It was on the fourth floor of a building, so it was like a destination to get to. I hung shows and got to know a little about that world. After we hung the show and had the opening, we would sit among the art for the next four weeks and I remember one month, six people came in. I was there every day; I saw six people. There would be a lot of days no one would come in. At one point, they didn't have anything for me to do. I was their first intern. I volunteered. I was a terrible intern. So they took three jars of screws, bolts and nails that were all mixed together, and asked me to make one jar of bolts, one of screws, and one of nails. So that's what I had to do for two days, sort out bolts and nuts and screws, and I thought, isn't this such a glamorous life? Something's wrong here. This is not what I want. That gallery went out of business, and I thought if I was going to stay in that world at all, it had to be much more democratically accessible, it had to be on the street level, interacting with actual people.

Did you have a reluctance to come back to art? Did you wonder if, because you made a name for yourself doing these other big things, people would accept you for being a fine artist? Was there part of you, too, that thought, “This is what I like to do. Who cares if people have an opinion or a preconceived idea of what I should be doing?”

Reluctance to do a gallery show? Yeah. It wasn't until eight years ago that Noah Lang at Electric Works invited me to do a show. I think I had done some drawings and started talking about a show. I had these paintings of animals with random text attached.

You can be very precious about yourself and your name, but I’ve never had that problem. I feel like if you can keep things separate and keep the quality of your writing the same, and take that as seriously as you ever have, and then over here, do the best as you can possibly do with your artwork, maybe it will be allowed. It's funny to think about it that way: “Oh, will they let me do this?” But it's hard to turn off that self-doubt, that feeling of “is this appropriate?” When I'm sitting there painting an egret or a prairie dog and writing random text on it, on the one hand, it's the purest joy I know. Creating a form. Unlike a book that's four years in the making, this art piece is done in a day. You can do something in one sitting, and there's a satisfaction in that. As long as it doesn't suck. There's nothing quite like it. And then there's that other voice that says, “You're 45 years old, this is not an appropriate use of your time.” But then you have to remind yourself, if it makes you happy and you find joy in it, and it makes people happy in some way, you can't overthink it. If somebody laughs at one of those and finds it interesting and wants to put it in their home or bathroom, it makes me beyond happy.

Animal first or phrase first?

I have a lot of phrases that I like that I will write down and attach to works later on. But usually with dogs, there's something about them that speaks, because they're all so stupid looking in the best way. I love them, but they do have an inherent lack of dignity that makes it funny to put something dignified next to them.

“Not a factor in 2016” with the Border Terrier is so good.

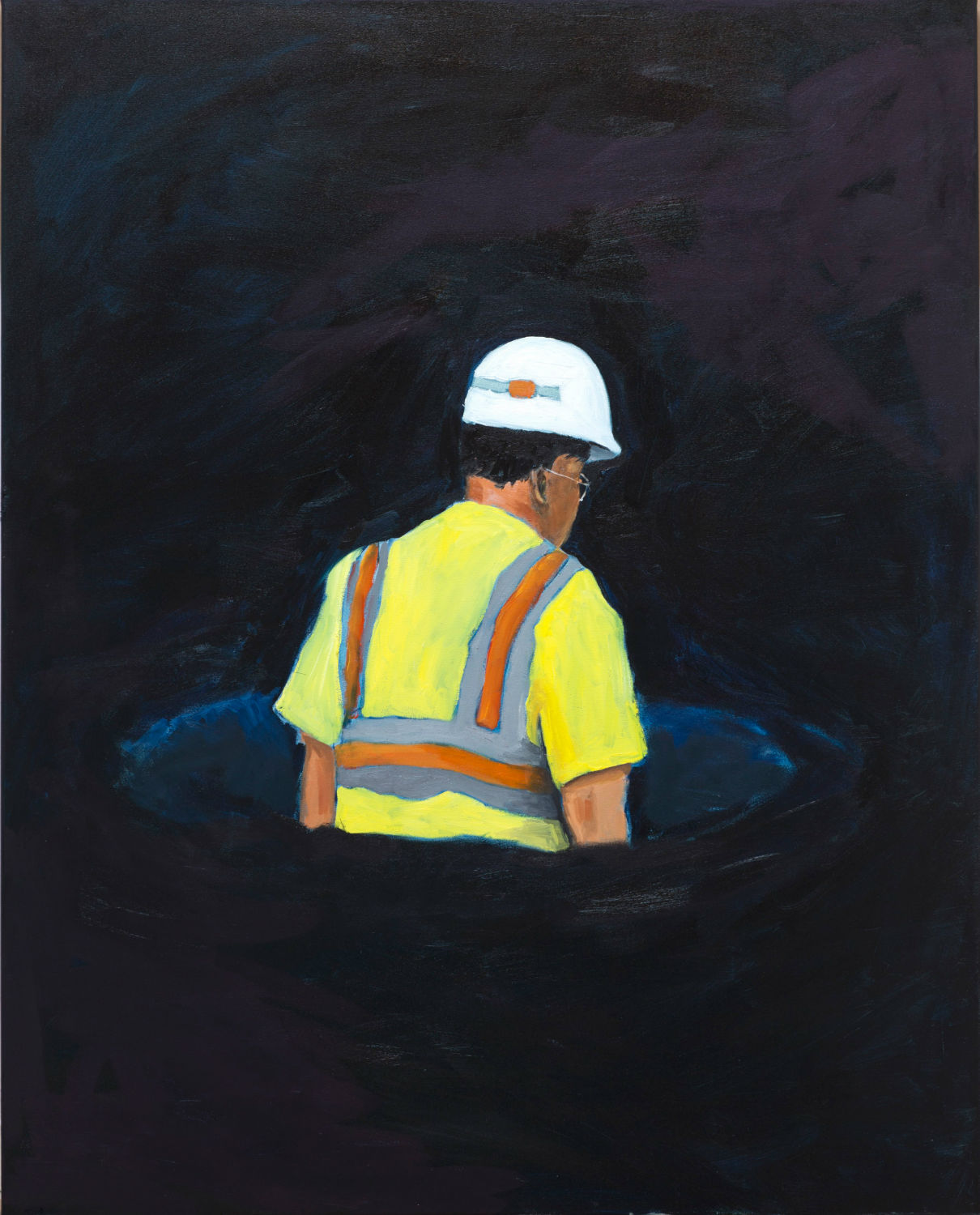

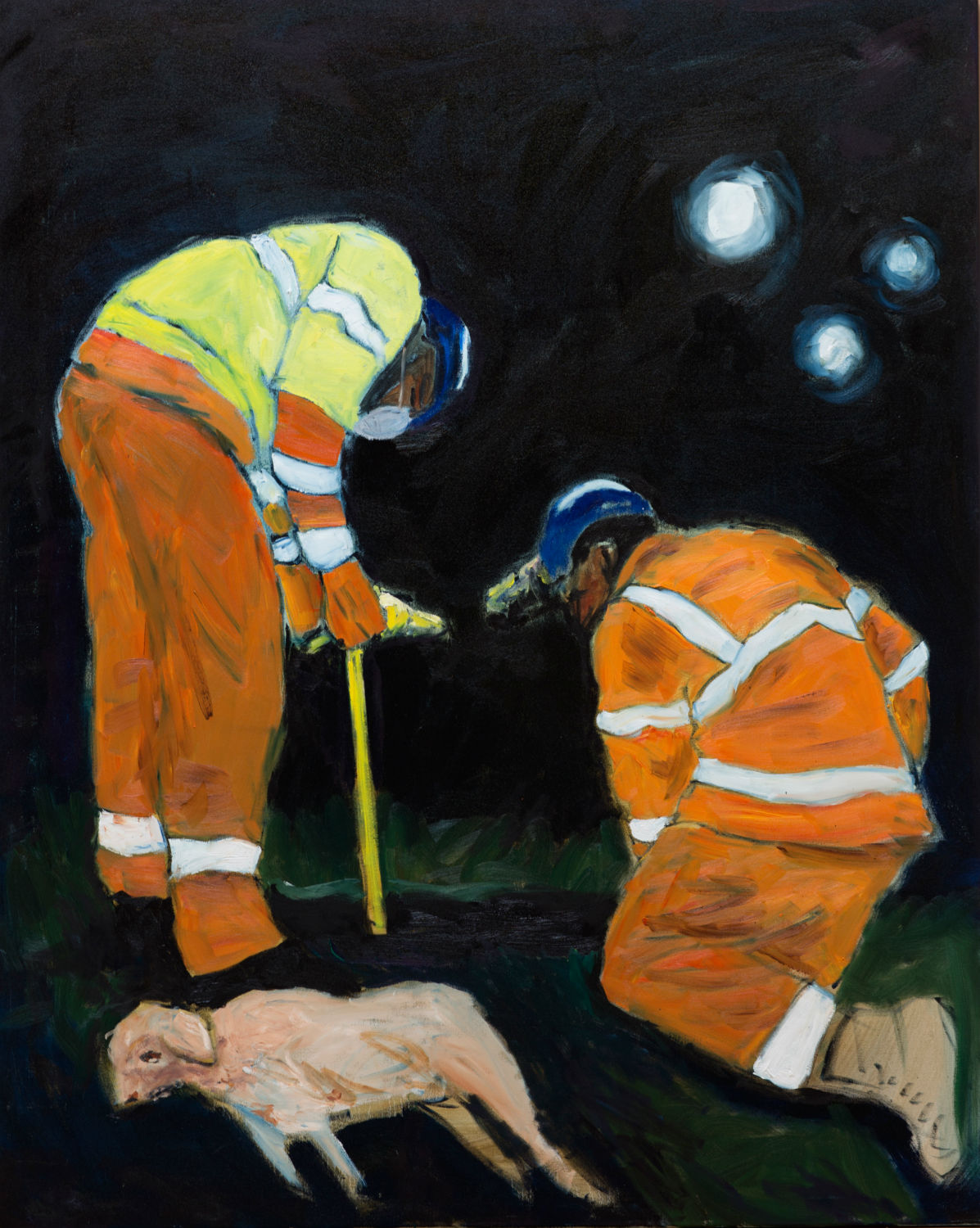

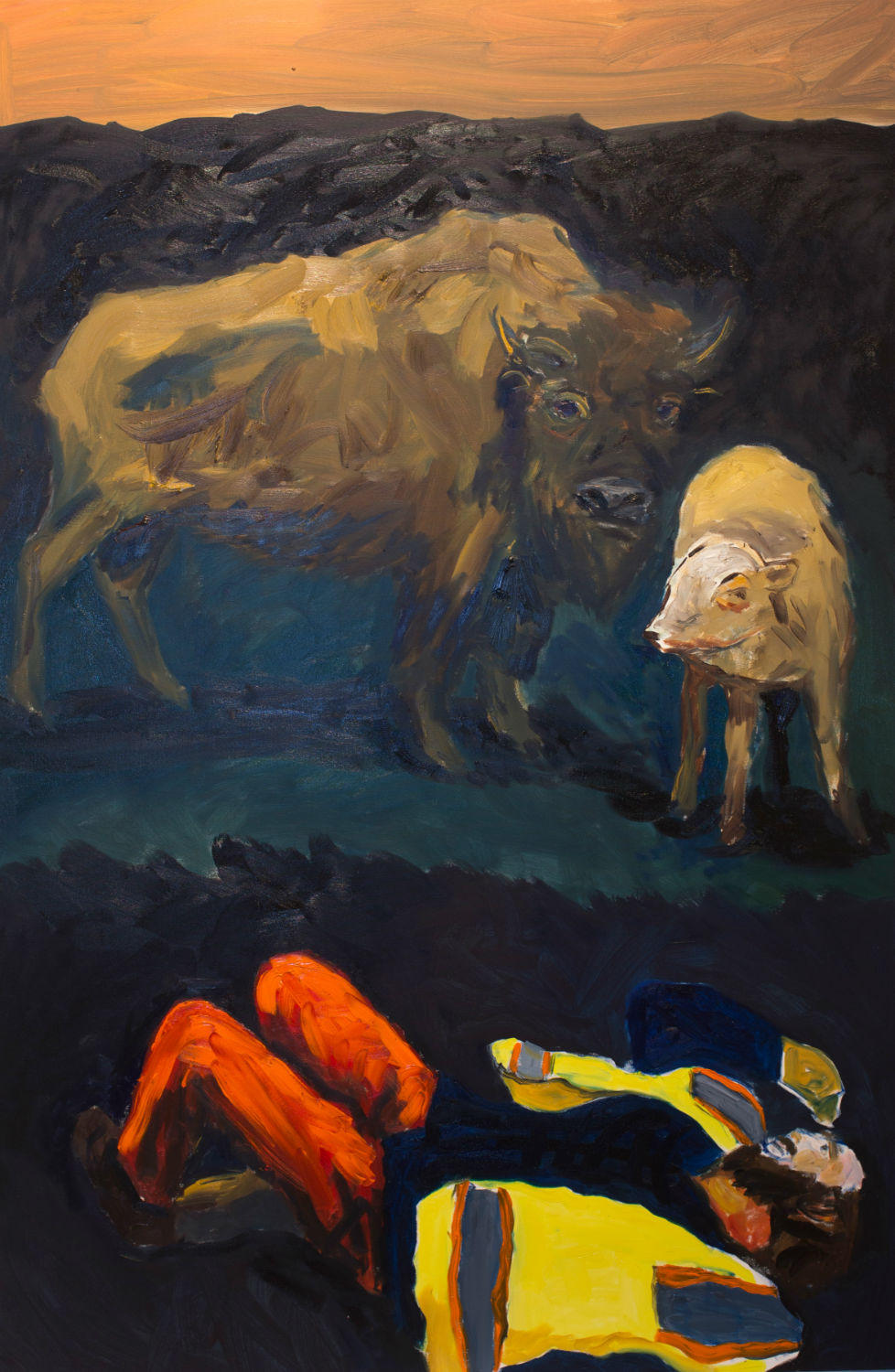

I’ll get on a kick where everything is political, or they're all biblical. It’s the first time I’ve ever worked in series. I would always study artists and see these twenty paintings in a certain series, and thought how I'd never done anything like that and didn't really know how it worked. I would always do one-offs, but now I see the fun in a series, see how one thing can lead to the other. I just staged a photo shoot near Rodeo Beach with a bunch of friends dressed up for construction because I have more construction worker paintings in my head. I have no idea why, but it feels like it’s something I have to do and want to do, and whether anyone likes them, I don't care.

We had a talk in the office recently about the animal work, how they are feeling our burden, feeling what we've done and how fucked up we are. The animals are just talking back to us, repeating our dumb sayings, left to try and understand the crap we’ve done to Earth and ourselves.

It started as a conversation between them and God. They're frustrated with their frailties and limitations, and either they're complaining to God, or they're quoting the bible back at him. If anybody had reason to be upset, it would be them because they get a raw deal every which way. But then a lot of it is how sometimes you can get at the ridiculous elements of humanity, like the idea of saying aloud or writing to your fellow man, “Marcus has sent you a link.” Those sentences that we have to speak on a daily basis that are so embarrassing.

But if you put it with an animal...

It makes it ten times worse.

Was painting more and more part of a confidence thing?

With writing a book, it was the old Malcolm Gladwell thing; however many times I get to the finish line, I feel like I know the course. So it doesn't mean that everything will always work out, but when you start something, you know the work ahead. It's generally true with painting now. Maybe not with this construction series, but when I sit down to paint a dog, I know how to do it at this point. I keep laughing because I can't get over the fact that it's something I'm doing. But there's my 18-year-old self that expected to be doing this, though I imagined creating big tableaus with a lot going on. It was a combination of the same kind of assemblage of characters, so the construction worker stuff is the closest thing to what I thought I was destined to do as a teenager.

Dave Eggers is creating kinetic sculptures as part of the ongoing Juxtapoz art program at the Outside Lands Music and Art Festival in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, August 5–7, 2016. His newest novel, Heroes of the Frontier, is at bookstores now.

----

Originally published in the September 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, available here.