Memory is a funny thing. It’s easily defined as a faculty in which our minds store information to influence future decisions, and yet contains so much more mystery, ambiguity, and moments oftransformation than the functional definition allows. San Francisco-based painter Mary Finlayson noticed this while spending time with her aging mother, witnessing her memories fadeand her personhood transform. Her latest solo exhibition at Hashimoto Contemporary LosAngeles, Flowers on the Wall, deals with the larger questions about memory and its more fadingqualities. How do memories persist in our minds to mold our understanding of ourselves and ourclosest relations? How do we remember, and what is left, when we can no longer tell the storiesthat shape us?

Before her exhibition opened on September 7th, Finlayson spoke with Hashimoto Contemporary’s Katherine Hamilton about memory and her mother, her shifting national identity, as well as how women’s obfuscation in the arts has continued to inspire her vibrant aesthetic.

Katherine Hamilton: Something that often stands out about your work is how objects represent people or specific memories, using the still life as a form to explore something larger, more grandiose. Have you always gravitated towards this subject matter?

Mary Finlayson: When I first started out, my work was much more personal and always felt deeply private. Because of that, I struggled to share my work with an audience. I was at a stalemate for a long while—there was a good three year period where I stopped painting all together.

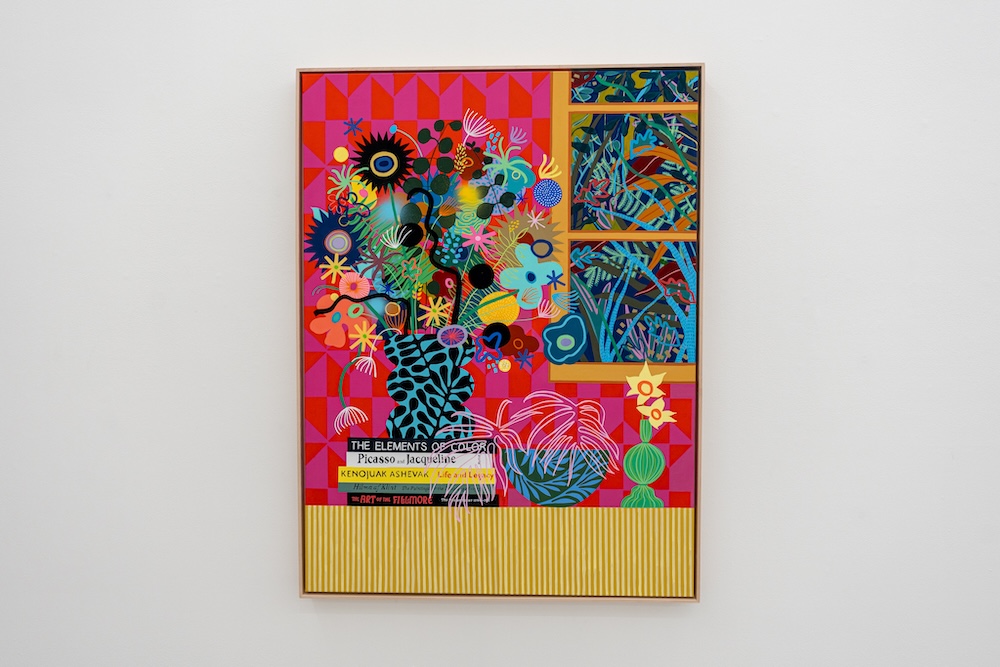

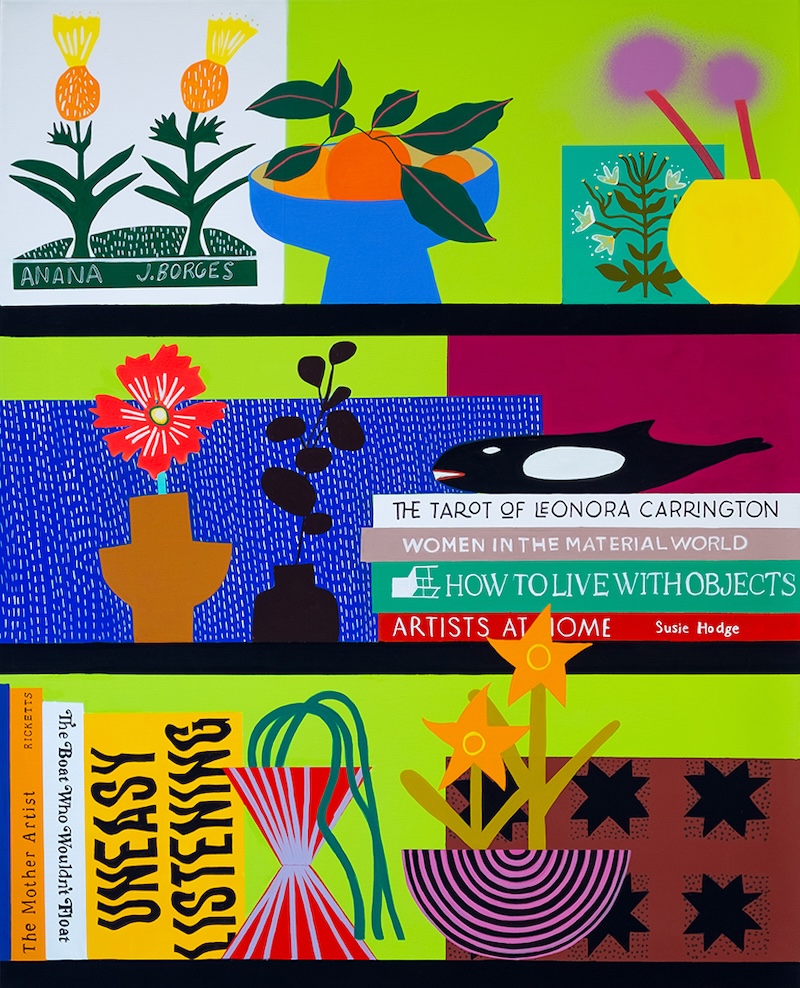

I started painting still-lives almost by accident. Really, it was just to paint again with less pressure. I set up a little scene of plants and books on my deck as an exercise, but as I was working it started to click. I could work with the same ideas but do it in a much more coded way that would be easier to share with an audience. There’s a freedom from interpretation that I didn’t have with my previous subject matter.

Why do you think this “genre” of painting has stuck around for so long? How do you think people—artists and viewers alike—connect to it?

Still life painting feels like a snippet of life where the audience is a voyeur, seeing into these private, interior moments. It’s an invitation in, but on the artist’s terms. In my opinion, this is why this genre has stuck around for so long. The audience is freed from a level of pressure to understand the artworks’ “true” meaning: they’ll either relate to the pieces or they won’t. The playing field between the audience and the artist is leveled, in a way.

I read somewhere that you begin your paintings by depicting women, but they turn to objects by the end of the painting. Can you say more about this process? What role do women play in the inspiration of your work?

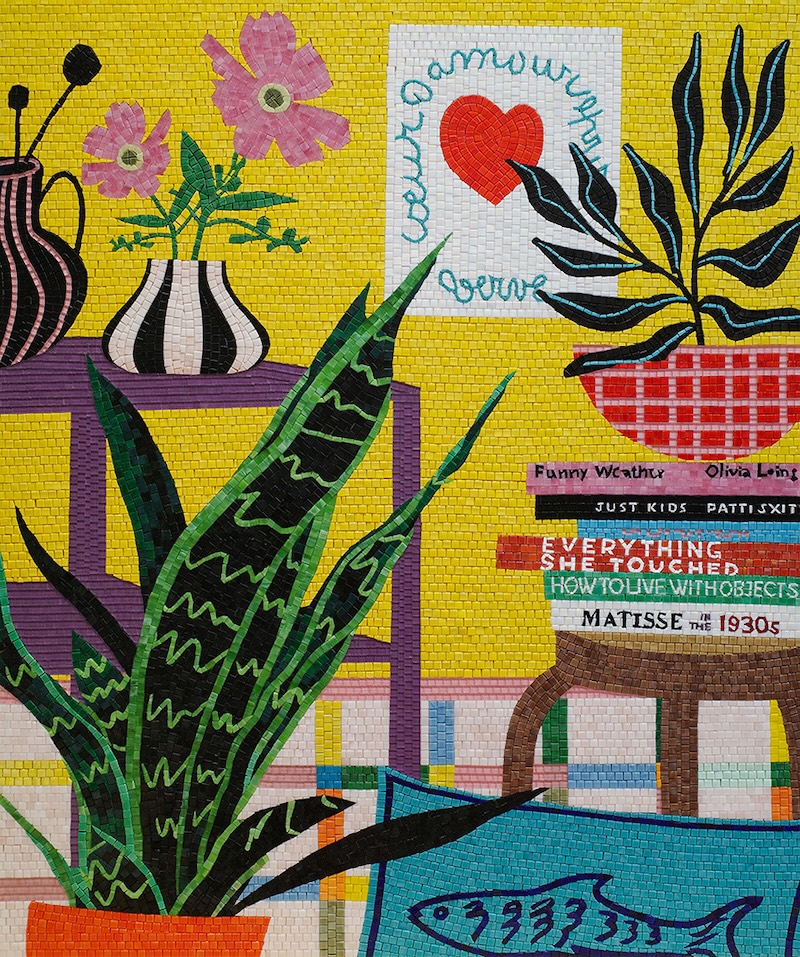

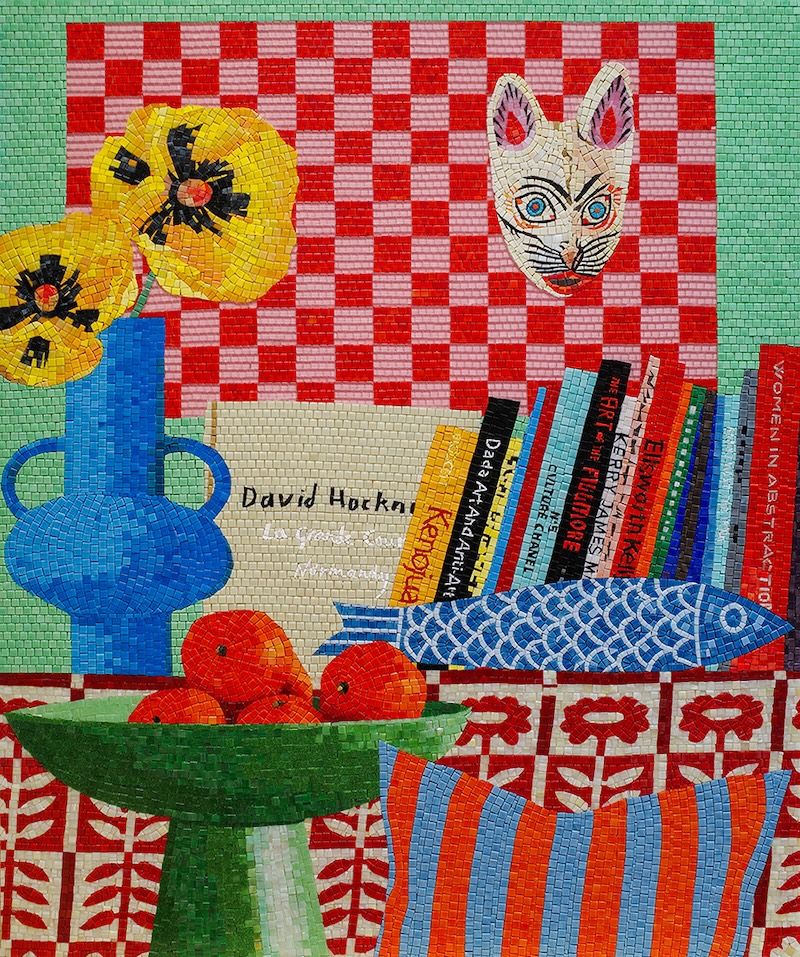

Okay, I absolutely love this idea, but I can’t say it’s entirely true of my process—though now I’m wishing that maybe it was! Most of my paintings and mosaics contain references to women, but not always. Largely, it’s due to the pieces being snippets from my life and experience, whether from girlhood, womanhood or motherhood. I like to include trinkets passed on from friends like books or seashells and oftentimes flowers. I occasionally use the objects as stand ins for people in my life. In the most recent body of work, most items came to me by way of my mother, my children, my sisters and friends. I am also trying to pay respect to the crafts traditionally done by women, and this is especially true of the textiles included in my work.

Speaking of women, this exhibition is, in a way, about your mother. You shared that your mother was diagnosed with dementia while you were working on these paintings, leading you to think more deeply about memory. Who is a person when their minds no longer hold onto their past? Not to be too psycho-analytical, but what did you learn about your relationship with your mother through this process?

I’m not quite sure how to put into words what it is I’ve learned about our relationship through this process. The best way I can articulate it is that there’s a connection between my mother and I that I didn’t fully understand before. I’ve been stuck seeing her solely as a mother most of my life and had failed to see her beyond that one role. I’m starting to understand her in a broader way and see how her path has become my path without me even knowing.

As my mother’s memory began to shift, so did her construct of time. It’s made me see how all the parts of ourselves are continuous and how we experience these phases of ourselves somewhat simultaneously. The child in you is always with you, as is the adult, the parent, etc. You’re you in the present but you’re also never not the thing that came before.

Before this exhibition, did you conceive of specific books, sculptures, plants, as specific people? Or is the relationship typically more 1:1?

I tend to plan the compositions quite thoroughly ahead of getting started and then add the book titles and objects as I’m painting. Many of the items are in my studio so they’re easy to reference as I’m working. My ideas tend to shift and evolve as I’m working, so while I like to have a complete vision of the piece, I also leave space to add different objects and ideas as the painting evolves.

There are a lot of references to specific memories of my mother in the show, this is especially true of the flowers. Between growing up on the west coast and my mom owning a flower shop I was pretty surrounded by plants and flowers as a kid.

You spoke about how your mother owned a flower shop, and that, for you, flowers are always a link to her and your memories together. Are there any moments in these paintings that are direct renderings of memories with your mother?

There are quite a few. I included bleeding heart flowers because I always wished she’d not mention their name, at age 8 I’d envision actual bleeding hearts when seeing them. Bluebells were her favorite flower back then, so by default they became mine and those showed up in a few of the pieces. There’s a snip of wisteria in one painting that came from a vine that was wrapped around a massive Douglas fir tree in my childhood front yard. It had to be cut down one year and I always missed that wisteria desperately as a kid. Another painting includes the book Are you there God it’s me Margaret because my mom gave that book to me when I was 9 years old. After reading it I became absolutely obsessed with puberty. Even mentioning the book now makes me cringe with embarrassment for that time.

Finally, the Dahlias were flowers that we would always buy from a farm stand across the street from our home on Vancouver Island where I lived as a teenager. They were $2 a bunch and she always had bunches of them in the house when they were in season.

You focused primarily on your paintings for many years before adding mosaics into your practice. When did this shift start?

I first thought about making the mosaics while I was doing a residency at Otis College in 2017 and they didn’t become a reality until 2019. It was another year before any galleries were interested in them, so the first one sold in 2020 with JoAnne Artman at the Affordable Art Fair in New York right as things were beginning to lock down. It was another 3 years before I included them in a gallery show, the first being at Eleanor Harwood in San Francisco. I’m very excited to continue to expand my work in this medium and am so grateful for finding a great team of skilled artisans to help me find a way to make them a reality. The biggest learning curve for me was learning how to work with the material without getting my hands absolutely shredded and what size to work with where they aren’t too heavy for a wall, but not so small that the detailed work becomes impossible.

There are several allusions to folk art in the books and objects you choose to depict in these works. Since you’ve been working on mosaics, and you’ve mentioned wanting to venture into textiles and weaving, I wondered if you were the type of artist who has particular feelings about the divide between “craft” and “art”? Particularly because you are a woman artist alluding to work by other women artists, whose practices were historically relegated to the realm of “unserious craft,” I was curious about your relationship to those legacies as you plan out how the colors and forms play in your various mediums.

I absolutely love folk art. Some of my favorite artworks would be considered either folk art or outsider art. I think it’s an undervalued, under-recognized genre. A few summers ago, I ran an art workshop in Nova Scotia and was exposed to Canadian folk art that I had never seen before. I had the great fortune of seeing the Maude Davis exhibition at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia where they made a replica of her home and had a great retrospective of her work.

I like to show these influences in my work because it’s something I seek out and have in my home. I am also trying to honor it by bringing it to the foreground. I make paintings about paintings, weavings and hand carvings as a means of appreciation and representation. I include the needlepoints, quilts, and other “craft” pieces as a means of paying respect to this lineage of work that has been passed from one hand to another between mostly women. These “crafts” have traditionally been ignored, been systematically undervalued, and are at risk of being forgotten.

My sister is a quilter and my mom a knitter. Their skills go back many generations as my mother taught my sister who learned from her aunt and her aunt from her mother and so on.

This is perhaps a niche question, but you and I are both Canadian girls—born and raised on the West Coast. Something I’ve noticed about the contemporary Canadian art scene is that there aren’t a lot of painters. Or, painters often move from Canada to the UK or the USA to pursue their career. Why do you think this is? Did you notice yourself being treated differently as a painter in the US than you were in Canada?

This does seem to happen quite a bit. The art industry in the United States is so strong that it has an almost gravitational pull for many artists.

As a kid growing up in Canada in the 80’s and 90’s, it felt like New York, Los Angeles, or San Francisco were the only places to be an artist. My access to art was by way of the Vancouver Art Gallery and at that time most of the Canadian artists I recall seeing were either painters from the Group of Seven or photo-conceptual artists from the Vancouver School like Jeff Wall, Rodney Graham, and Ken Lum. There weren’t a lot of contemporary Canadian painters being shown and, with the exception of Emily Carr and Agnes Martin, far fewer female painters.

I imagine the scene has changed quite a bit since that time, but back then I did find it a hard place to find a role-model. When I moved to SF, somehow the path felt easier and that was a big factor in deciding to stay. I am forever grateful for the welcoming audience I found here.

People often see your artworks as influenced by Henri Matisse, Stuart Davis, Josef Albers, David Hockney, and other European and American painters. On the topic of Canadianness, I noticed monographs of Inuit painter Kenojuak Ashevak and honorary Canadian Henry Moore in this latest body of work. Do you feel like your influences are expanding as you sink deeper into your practice? Or have those references always been there, but perhaps obscured?

This past year my husband and I applied for American Citizenship. I love living in the U.S. and it has been a very good home to me and my family, but this next stage in our immigration has brought up a lot of questions for me about my “Canadianness.” How can I be a Canadian if I am also an American? It’s been something I’ve been processing over the past while, so in a way as I’m becoming more American my references are becoming more Canadian. I don’t want to lose that aspect of myself and I want to spotlight the artists I admire and share them with anyone who comes in contact with my work.

Circling back to the themes of this exhibition, there are all these depictions of other people in your life that are immortalized through your artwork. In thinking about memories, and which ones last, what do you want people to remember about Mary Finlayson?

I feel like my career has just begun in some ways, and I’ve been so focused on my work I haven’t had time to zoom out and think about the totality of the work I’ve done. For now, I’m just happy to paint and explore my craft.

Flowers on the Wall is on view through September 28th at Hashimoto Contemporary in Los Angeles