When did Mexico become one of the world’s hottest art destinations? The Mexican capital, in particular, known for Aztec architecture and storied murals, is thriving in a dynamic creative scene as artists like Perla Krauze, Gonzalo Garcia, and Fernando Laposse make their mark in cultural conversations. Today, audiences and stakeholders are flocking to Mexico, or alternatively, sharing works inspired by the nation’s history with global audiences at some of the world’s most frequented international galleries and museums; simultaneously, thought leaders are launching artist-run spaces like the Unión Residency program, a lab offering personalized mentorship for narrative-based creators (founded by artist, collector, and curator José Castañeda Lepov), and experimental pop-up shows with the goal of nurturing local artists.

The latest wave of artists is forging their own paths in a country where art has long played a role in history and culture, tracing back to the origins of Mexican art in pre-Columbian civilizations, the arrival of the Spanish, and the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s. In the 20th century, iconic artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera achieved iconic status—but what does contemporary art look like in Mexico today? And how have the arts chronicled the country? These questions are integral to understanding the works of Fernanda Canales, Bosco Sodi, and other architects and artists in Mexico.

Let’s first examine the history of art in Latin America. The earliest Mexican paintings were completed millennia in the past, with Mayan, Aztec, and Incan civilizations initially focusing on architecture and sculpture. Painting on ceramics dates back to the Purron agricultural phase from 2300 to 1500 B.C. Codices, or old book-like publications, featured pictures rather than written text, and readers will note that colors were often used symbolically in these ancient works. The yellow hue of corn symbolized food, for example, while black implied weaponry and red indicated blood. Common themes of religion and politics are reflected in the Olmec civilization, which crafted a series of large-scale sculpted heads featuring unique facial expressions, each wearing a helmet. Though the precise reason these heads were constructed remains unclear, some believe the works were sculpted to highlight the Olmec rulers’ geopolitical power between 1200 and 400 B.C. Researchers claim the sculptures were eventually moved up to 60 miles from where they were first constructed, likely for political reasons during the Middle Formative Period from 900 to 300 B.C., a transition phase from smaller architectural villages to denser towns. Mexican culture evolved significantly during this time, with Olmec influences extending to Oaxaca, Chiapas, Guatemala, El Salvador, and the Valley of Mexico. Subsequently, the Late Formative Period from 300 B.C. to 100 A.D. featured the spread of more complex societies, with hieroglyphics and calendrical calculations taking shape; this timeframe is associated with Tres Zapotes, Izapan, and early Oaxacan artistic styles. The most famous pyramid in Latin America, the Pyramid of the Sun, at a staggering 200 feet tall, was erected in Teotihuacán during this period between 1 and 250 A.D. Meanwhile, the Aztec Calendar Stone, or Sun Stone, depicts the Aztec sun god Tonatiuh surrounded by symbols that comprise the Aztec calendar, now housed in Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology and among the nation’s best-known pre-Columbian works of art.

How might the Spanish have influenced Mexican art history? Moving on to the Colonial Era, during the Spanish rule of Mexico from approximately 1521 to 1821 A.D., the country’s art scene experienced a drastic shift. Notably, the arrival of Christianity led to the construction of new churches with European décor and depictions of the Virgin Mary, Jesus, and the cross. Despite the resulting artistic shockwaves, native techniques to Mexico like feather art—popular before the Spanish arrived in Latin America—remained popular and were often used alongside more traditional Christian decorations. Mexican artists continued to forge unique artistic identities while the Spaniards were in power, a trend that continued when Mexico regained independence in 1821. Here again, artists set out to separate their home country from its colonial past.

Nearly a century later, the Mexican Revolution produced new works of art celebrating triumph in the face of hardship. In 1911, the Mexican people overthrew Porfirio Díaz, a dictator who only supported artists of European descent during his rule. During the revolution, art prioritized self-expression steeped in introspection, as works shed light on anti-authoritarian and pro-democratic thinking and as egalitarian and utopian schools of thought transcended the country’s pervading political militance. A muralist movement began to take shape as well, with artists embracing themes like the human condition, the significance of struggle, and Mexican life and identity. These socio political issues are still prevalent today, apparent in paintings and sculpture, folk art and photography, and even in Mexican cinema. In 2024, contemporary Mexican artists will continue to innovate, blending history and modernity into something entirely new, as in estudio muro, also the brainchild of José Castañeda Lepov, who specializes in the design, painting, and installation of modern murals throughout Mexico City.

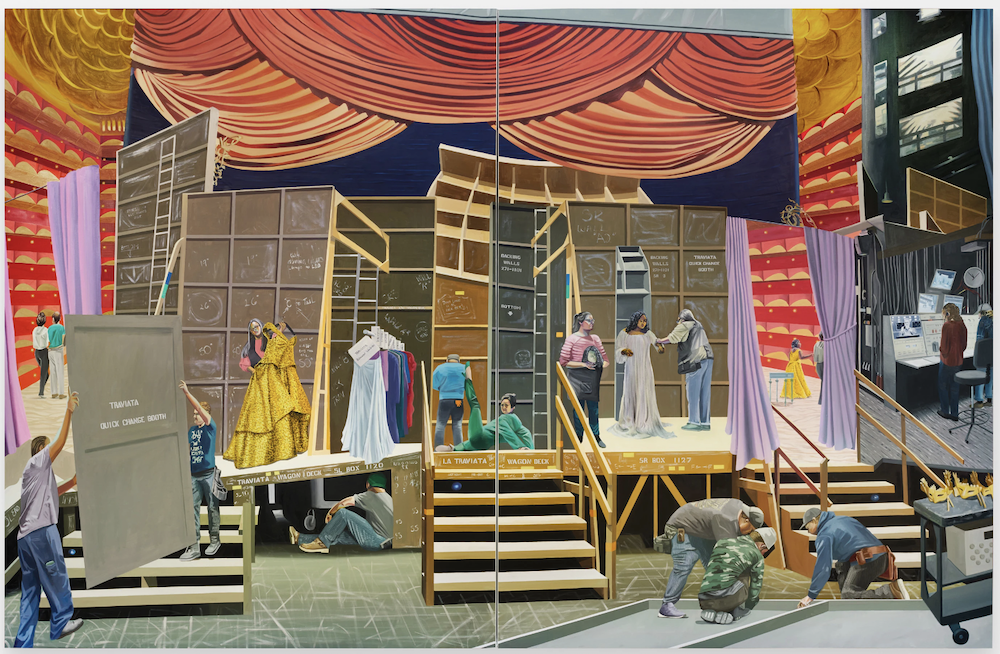

One might argue that contemporary Mexican art is founded on the use of local materials. For Fernando Laposse (b. 1988, Paris), a designer born in France to Mexican parents, material sourcing and cultural context are critical. The artist, who divides his time between London and Mexico City, collaborates extensively with the Tonahuixtla community, a group of Mixtec farmers in southern Mexico. With their input, he develops techniques that help residents repurpose, and ultimately regenerate, traditional agricultural practices. Specifically, Laposse transforms materials like corn husks into refined pieces, all while speaking to the importance of environmental activism and cultural sensitivity. The artist sheds light on complex topics like climate change, migration, and indigenous rights in his intricate designs, in many ways helping to counter the nation’s colonial past. Like Laposse, Aliza Nisenbaum (b. 1977, Mexico City) leverages her Mexican heritage to elevate themes like visibility and representation. Based in New York, the Columbia University professor paints colorful portraits that humanize underserved global communities, offering an intimate look at diverse cultures and relationships. Through an often political lens, Nisenbaum gravitates toward the popular aesthetics of Mexico, such as the intricate textures, patterns, and bright colors of her upbringing. No identity is homogeneous, she notes, and this viewpoint is apparent in the artist’s paintings. Nisenbaum’s works showcase the plurality of humanity, our traditions, and micro-differences, with an emphasis on solidarity, sensitivity, and access.

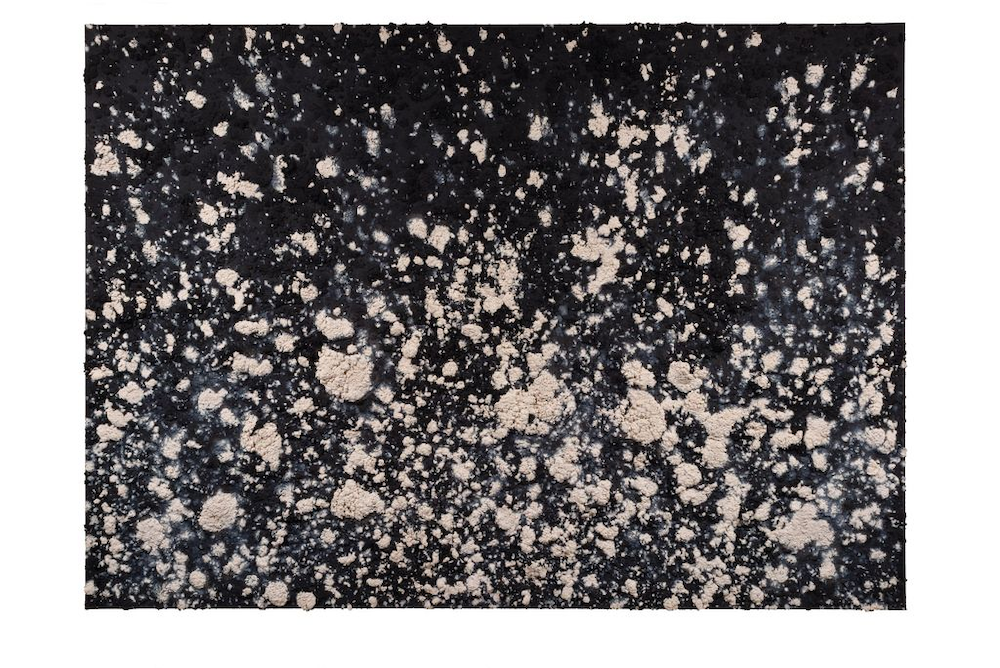

Architect Fernanda Canales (b. 1974, Mexico City), who celebrates a similar sense of place, studied in Spain before returning to her native Mexico, where she has received international acclaim as one of the world’s leading architects. Growing up in the northern Monterey section of Mexico, the sun and the mountains factored extensively into her identity. While she and her family embraced the sun’s heat, Canales noticed that outsiders would often reject it, pulling the shades or turning up the air conditioning, and only rarely leaning into their environment. Marrying stunning interiors with the exterior landscape, the architect has made a career of inventing seamless minimalist spaces with the aim of inspiring others to connect with their surroundings. This unification of interior and exterior environments is also prevalent in the works of Bosco Sodi (b. 1970, Mexico City). Drawn to Zen philosophy, the artist has embraced the crudeness of raw materials such as ground chalk, sand, and dirt to bring his large-scale paintings and sculptures to life. Sodi believes all materials have their own souls and that by removing any preconceived notions beyond each work’s immediate existence, he can make art influenced by the local climate. Inspired by his own lived experience in Mexico and Japan, Sodi remembers visiting Mayan ruins with his mother as a child, and acknowledges how these trips fueled his appreciation of raw materials. His current Harvard Art Museums site-specific installation Origen, on view through June 2024, features a series of untitled terracotta spheres that examine the earth’s most basic forms, blending traditions like sculpture with contemporary minimalism, employing Zapotec techniques, and using clay sourced from Oaxacan artisans. Like Canales, Sodi relies on his surroundings to create these works of contemporary art. Perla Krauze (b. 1953, Mexico City) is similarly inspired by ruins and archaeology, working with a range of materials to craft three-dimensional pieces influenced by volcanoes, fossils, mountains, and other artifacts and landscapes inherent to Mexico. Erasure and memory are central to Krauze’s process, whose work relies heavily on Mexican history and topography.

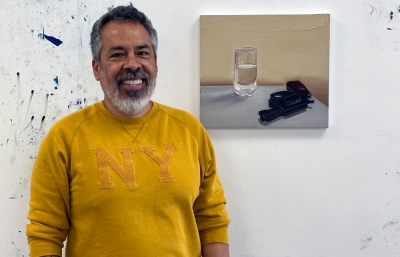

And what about politics? Gonzalo Garcia (b. 1988, Puebla) is intrigued by Mexican violence, often in reference to the progression of the nation’s middle class from the 1970s onward. Focusing on film and painting, the artist’s work is founded on eroticism and ambivalence. His recent works are more explicit, especially the pastel florals and the overgrown bouquets representing human flesh, past stomach problems, and loss of physical control. Often through the lens of being queer in Mexico, he explores the nuances of violence and death. By referencing Mexico’s student protests from the late 1960s, Garcia blends past and present, combining his personal experience and Mexican history into pink, purple, and cream-colored works that contextualize the body in intimate spaces. Other artists steer clear of politics, emphasizing the mind over the temporal. Nicolás Guzmán (b. 1983, Xalapa) has infused painting, sculpture, performance, printmaking, installation, photography, and video into his practice, taking a multimedia approach to examine art, the role of materials, and the limits of representation. Focusing on color, matter, and space, he views art as an exercise of thought, finding inspiration in the philosophies of Michel Foucault and Arthur Schopenhauer. His film The Dream of the Tordo (a black bird similar to a raven), which prioritizes the imagination over political activism, has a tentative release date of 2025.

Looking forward, stakeholders believe Mexican artists and thought leaders will continue to make an impact that transcends borders. Curator and art historian Amanda de la Garza (b. 1981, Monclova), the current director of the University Museum of Contemporary Art (MUAC) in Mexico City, will soon leave her post to serve as the Artistic Deputy Director of the world-renowned National Museum and Art Center Reina Sofía (MNCARS) in Madrid, Spain. Multimedia artist Erika Harrsch (b. 1970, Mexico City) reinforces this international trajectory with her Passport project and accompanying book Borderless – United States of North America (2009), which highlights the porosity of geopolitical boundaries in the context of a single realm composed of the U.S., Canada, and Mexico (members of the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA). Harrsch’s interactive installation includes an original passport seal combining symbols of the three countries; at the center, a monarch butterfly symbolizes hope, change, and the future of human rights. The artist, who has lived and worked all over North America and Europe, notes that we have more freedom than immigration policies might suggest and that Mexican artists will continue to gain notoriety in a global context. —Charles Moore

Readers can learn more about Mexico’s growing contemporary art movement from many resources, including the forthcoming book Global Conversations: Mexico, which will include detailed interviews with the artists highlighted in this essay. This text was originally published in our FALL 2024 Quarterly