Expect no gossamer pastel butterflies or smoldering dark portraits at SFMOMA’s Nam June Paik retrospective, but do expect to marvel at his brand of exquisite, which will be on display in over 200 works made over a five-decade career. Declaring that “Nature is beautiful, not because it changes beautifully but simply because it changes,” the mercurial Korean artist was a trained classical pianist—who later became friends with Yoko Ono. He envisioned and engineered the fusion of multimedia and multiculturalism, predicting, in 1974, in his own words, “electronic superhighways.” I spoke with Rudolf Frieling, Curator of Media Arts.

Gwynned Vitello: What were your goals in organizing this show?

Rudolf Frieling: From a curatorial perspective, we felt it was time, 20 years after his last US retrospective, to introduce this global visionary to a younger generation and highlight an artist who has consistently challenged our definition of art through technology and his practice across all media. From an institutional perspective, it may be surprising that he has never had a major survey on the West Coast. On top of that, we’d all be hard pressed to find an artist who has addressed and lived such a transnational and global life as Nam June Paik. Lastly, SFMOMA has had incredible fortune in acquiring a major body of work covering all periods of his life so we can tell his many stories within the strong presence of our collection.

“The culture that’s going to survive in the future is the culture that you carry around in your head.” How do you present the work with that in mind? Did he show his work frequently, and how?

Fellow curator Sook-Kyung Lee from Tate Modern and I were eager to pursue a balanced perspective on Paik’s work, focused not only on his pioneering role in championing technology in art, but also emphasizing the the importance of artistic collaboration, as well as the ongoing dialogue between Eastern and Western legacies throughout his career. We were inspired by his many memorable quotes and aphorisms that bridge the gap between cultures in surprising, humorous, and at times, mysterious ways. His writings, recently published in English for the first time, show the wit and spirit of a Fluxus artist, as well as a knowledgeable and avid reader of philosophies and histories. What Paik does best—to give an example—is to jump from the figure of a ninja to the properties of a satellite and find that they basically do the same, that is, reduce distances. Paik was always able to “open circuits” technically and intellectually in his associative thinking across cultures and categories. Visitors will enjoy and remember this irreverent, yet caring approach to culture, from The Beatles to cybernetics, to the writings of Eastern philosophers.

How will you stage the entrance to the show in order to engage visitors? I’m glad you’re referencing what I’ll call his verbal pronouncements, which are very helpful in understanding the work.

We will feature Paik’s words, often illuminating how music and its traditions continued to be a foil for his entire career. Highlighting his thinking, music and other ways of performing, but also his artistic persona as a multilingual Korean artist in the West are key to our approach. Another is to foreground his firm foundation in the history of music and what he calls his “action music,” a way of always coming back to musical influences, John Cage being the most obvious. He considered his own work—in his own words—“not not music.”

His nephew, Ken Hakuta, felt that imperfection was part of the art, and in fact, Paik said, “When too perfect, lieber Gott bose [God is not amused].” How did he evolve from young classical pianist to participant in the Fluxus movement?

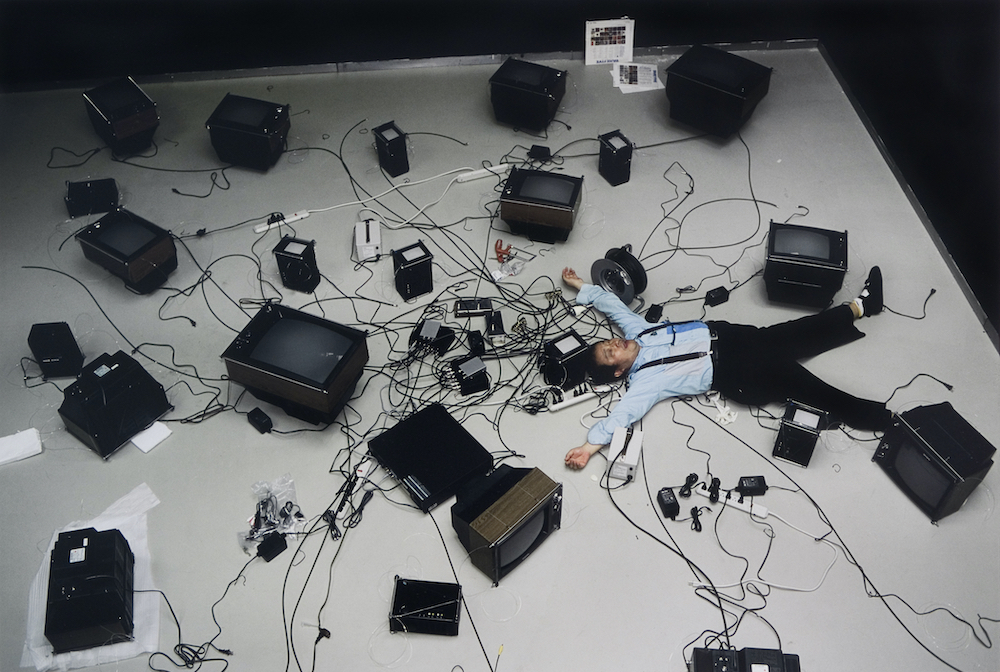

As you point out, he didn’t mind imperfection, he even cherished it, and was keen on producing new work—”I go where the empty roads are.” The way that he embarked on a trajectory of exploring opportunities, from early video technology, to analog synthesizer, to laser technology, was his way of making a name for himself. That said, he never forgot that an artist can never walk alone, especially with technology. He was eternally grateful to both his circle of friends, including the Fluxus artists, but also Charlotte Moorman, John Cage and Joseph Beuys, and also his long friendship with Japanese engineer Shuya Abe. As Paik put it, “In engineering, there is always the other…” meaning you cannot do it alone.

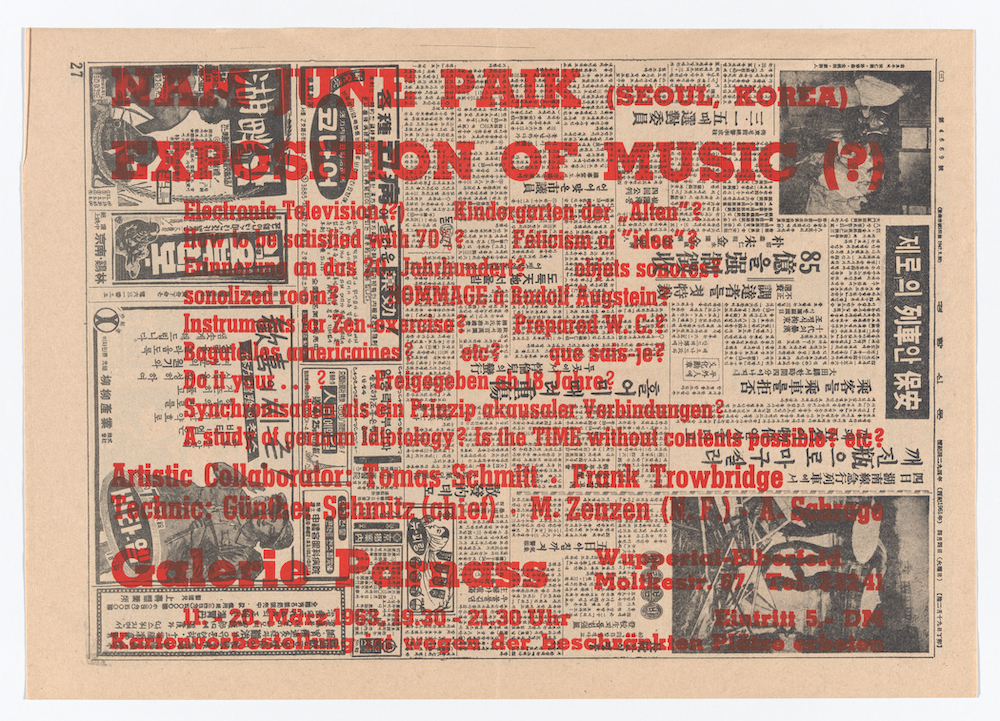

How will you incorporate music in restaging 1963’s Exposition of Music—Electronic Television?

We dedicate an entire gallery to the groundbreaking show, though not a restaging, as that would take up an incredibly large space and necessitate securing many more very fragile loans. Think of it as a cross section of the most important aspects. We will be as interactive as we can, given the constraints of the pandemic. “Foot-Switch” can fortunately be activated by foot and “Random Access” will be experienced via museum staff. In an adjacent space, we’ll show an excerpt of the historic Stockhausen happening, titled “Originale,” a wild event which originated in a collaboration with painter and salon hostess Mary Bauermesiter, later restaged in New York, again with Paik playing a seminal role as “action performer.”

How will you show TV Buddha, and did he practice Buddhism?

The artist created a whole series of different TV Buddhas over a period of almost 20 years, but we will show the 1974 iconic original in the first gallery as a nod to the importance of Buddhism as a reference point for Paik. He did not practice it as a religion or meditative practice until a 1996 stroke, but rather valued its influence the same as he would reflect on the legacy of Johann Sebastian Bach and Western classical music.\

TV Garden makes me wonder about his reflection, “Nature is beautiful, not because it changes beautifully, but simply because it changes.” He was no Thomas Kincaid, but did ever flirt with pretty, peaceful, or even comfortable?

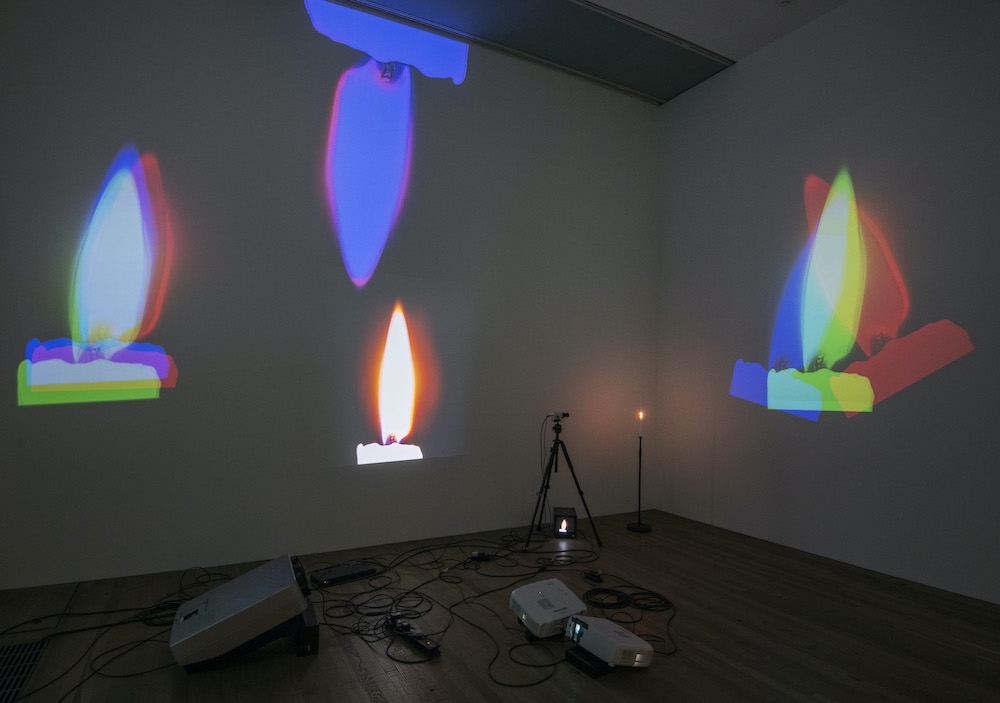

I wouldn’t say “pretty” because he just loved making things imperfect, odd, weird, or using objects in some state of disrepair. I can see a lot of “peaceful” moments, though, thinking about “TV Buddha” or “One Candle.” Whatever one’s personal response, it will invariably be colored by the experience of Paik’s sense of humor. Replacing the TV program with a burning candle is smart, deep and witty. His art is also challenging, noisy and loud, so you will never feel “comfortable” for very long while walking through the exhibition.

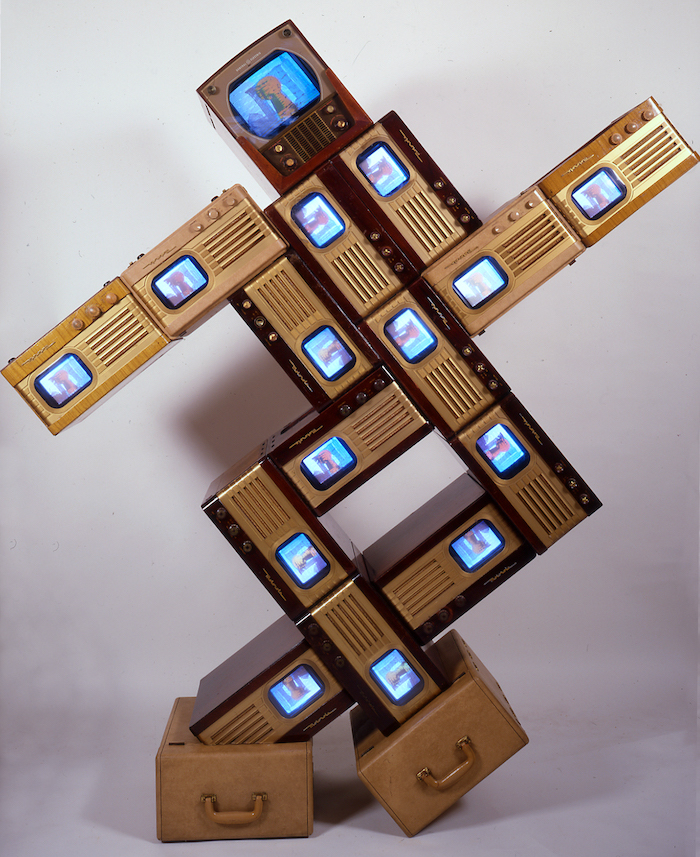

Will your presentation of two robots, one dedicated to composer John Cage and another to choreographer Merce Cunningham, be unique to this show?

Yes, the pairing will be unique to SFMOMA’s presentation, the main reason being that most of these sculptures don’t like to travel! With two of them already in US collections, and one being local, it makes sense for each touring venue to “localize” their presentation. We were thinking in pairs throughout the show, however, since the artist called the series a “family of robots.” I’m particularly happy about our opportunity to show two sculptures dedicated to partners in life and art, Cage and Cunningham, who were like family to Paik. Lifelong friendships and collaborations are a theme throughout, also exemplified by Charlotte Moorman and Joseph Beuys.

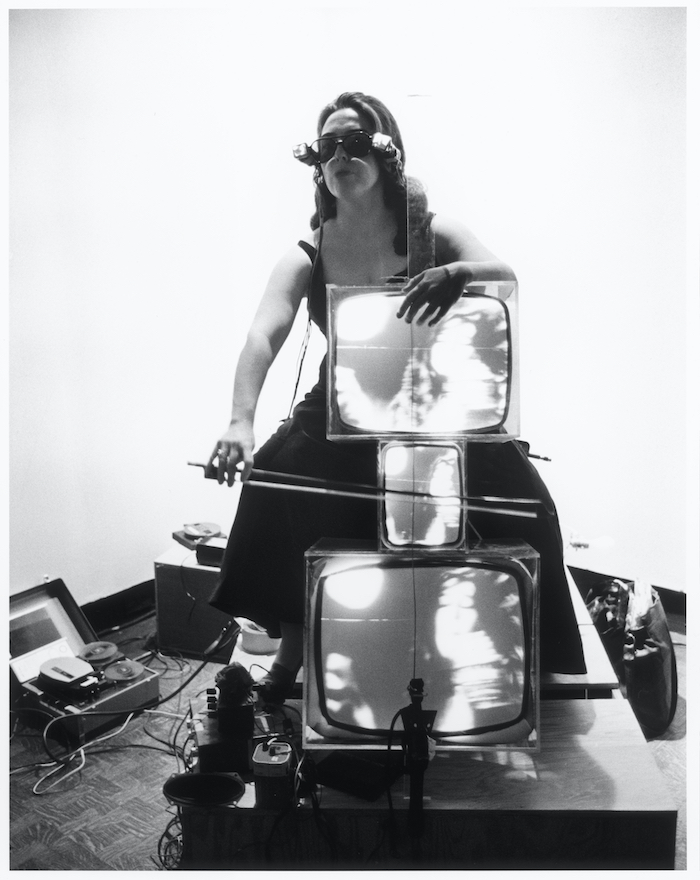

Will there be a reference to the cellist in the show, and can you say more about her influence?

Far from being a performer hired to execute his works, Charlotte Moorman was one of his most important collaborators and will be celebrated in her own gallery. She claimed co-authorship of many of their performances, embracing the conscious breaking of conventions and boundaries. She was the driving force of the New York Avant Garde Festival in the ’60s and ’70s, risking her career as a classic cellist, but gaining a place in art history. A fearless rebel way before the sexual revolution took center stage, Paik felt indebted to Moorman until her death in 1991.

For all his belief in collaboration, I’m curious about his observation that, “The only way to win a race is to run alone.” Can you clarify, especially since he believed that art was for everyone, and I don’t think of him as competitive.

Instead of competitive, I would call him ambitious and curious, but also collaborative and forward thinking. Paik realized early on that he was neither a gifted composer or musician, so he was looking for a way to forge his own path, to find the “empty road.” In 1963, he was the first artist to literally open up the closed circuits of electronic television. As a pioneer, you’re pretty much on your own, but later on, his energy and ambition made massive satellite projects happen because he was a connector and networker. In his friendship with Joseph Beuys, you’ll find he was humble enough to take a step back and be a supporting performer, as in “Coyote III'' from 1986.

Does Sistine Chapel close the show, and how much space will you devote to it ? What inspired the installation, and can you describe it in words?

Sistine Chapel precedes the final gallery that we call “Self Portrait,” but it’s arguably the culmination of this retrospective. The restaging of this enormous, immersive environment in close dialogue with Paik’s longtime assistant and now curator of the estate, Jon Huffman, was realized for this exhibition as an expression of Paik’s ambition in terms of scale but also as a way of showcasing his way of constantly remixing his own material. It’s a giant Paik Remix and smart way of showing that the 1993 Sistine Chapel was based on the circulation of images like Venice, the site of its premiere, offering a rich history of global commerce as a context. Paik didn’t mind a lineage connecting him to Marco Polo, the difference being that Paik could deal in immaterial goods, images thrown against the walls and ceiling in an unruly, riotous way, unlike the seamless simulations of virtual immersive environments that have populated the commercial and corporate world in the last decade.

He so much believed in the ideal of cultural free trade, in telecommunication crossing timelines and geography. How would he gauge the success of current technology companies?

Paik would probably assess companies to the extent that they would help him realize his own projects. But, jokes aside, he was a firm believer in two-way participation and engagement, who sadly passed away in 2006 before social media really took off. He would have loved to create his own channels with feedback. He openly acknowledged that America had “corrupted” him and that his minimal days were over. He integrated Japanese commercials without closed captions in his first TV broadcast “Video Commune” in 1970. Again, he just loved to break rules and I have a hard time imagining him going along with a corporate agenda. If a company wanted to engage with him on a marketing level, they would probably end up doing marketing for him, not the other way around. He understood branding like no one else. Community for him meant sharing the same space and tools, not necessarily the same messages.

Nam June Paik will be on view at SFMOMA through October 3, 2021.