“Anybody can be a world famous artist, instantly, if enough important people think they are,” Peter Saul says in a morning conversation, days after he returned from Miami Art Week in early December. Ironically, or perhaps ideally, the 87-year old painter had just been in South Florida for a public conversation with Beeple, and even if you think the artist most famously associated with NFTs speaking with one of the great American political painters of his generation doesn’t make sense, it’s 2021 and what we perceive as normalcy was thrown out the window in March 2020. Ironically, the last social thing I did before the pandemic was visit Saul’s Crime and Punishment retrospective at the New Museum in NYC in early March 2020, so to speak with him today, one of the most accomplished painters of his era who has seen a resurgence of appreciation in his work in the last decade, felt like a bookend to a masterfully complex time.

The occasion that Saul was speaking with Juxtapoz was his honoring at the New York Academy of Art’s Artists for Artists gala on December 14th, not only for his support of the school but for his massively influential voice and bodies of work on the current young generation of figurative painters that we have seen emerge so strongly in recent years. One of those painters is NYAA alum, Anna Park, herself a critically acclaimed painter who at the time of our interview had just been represented by international powerhouse Blum & Poe gallery. A torch has been passed in many ways, but just as important, Saul continues to immerse himself in contemporary figurative painting, and as Park expands on the legacy of past generations, she herself has become a voice for students at the school.

Evan Pricco: I think this is a great time to speak to you both, especially after Art Basel just happened. You know there's generations we're talking about here. Peter you've been a painter and exhibiting artist for decades and Anna you have emerged into this scene over the course of the last few years in such a special way. For you Peter, how important is it for you to still go and see things like Basel, and have this dialogue with both peers and new generations?

Peter Saul: I think it's important to be present as a human being and talk to people, but as far as actually seeing stuff, no, a fair hasn't been important to me (laughs). I mean this last time was great, really, I mean I felt very appreciated, and this is unusual and a good sign for the art. I haven’t thought about that so deeply so ask Anna that one. (laughs)

Anna Park: I think it's important, in whatever capacity, to immerse yourself. But as long as it's organic. I think what Peter mentioned being present is really important. I love going to shows and seeing other works. We're all kind of in this cacophony, this art world mess together so it's nice to find camaraderie throughout it all.

PS: Well, I would like to change my answer. I think it's important, too. I didn't realize when I got into art that it was going to be a real career thing, a profession. I thought it was a way to avoid going to an office building and being told what to do when you got there. And after about 15 or 20 years I realized, I was wrong and I began to know other artists and I admit it now that I found out the truth that is a profession like any other. That I want to get ahead, too. I want to get my share of art appreciation, I want to talk to the other artists and find out what they think.

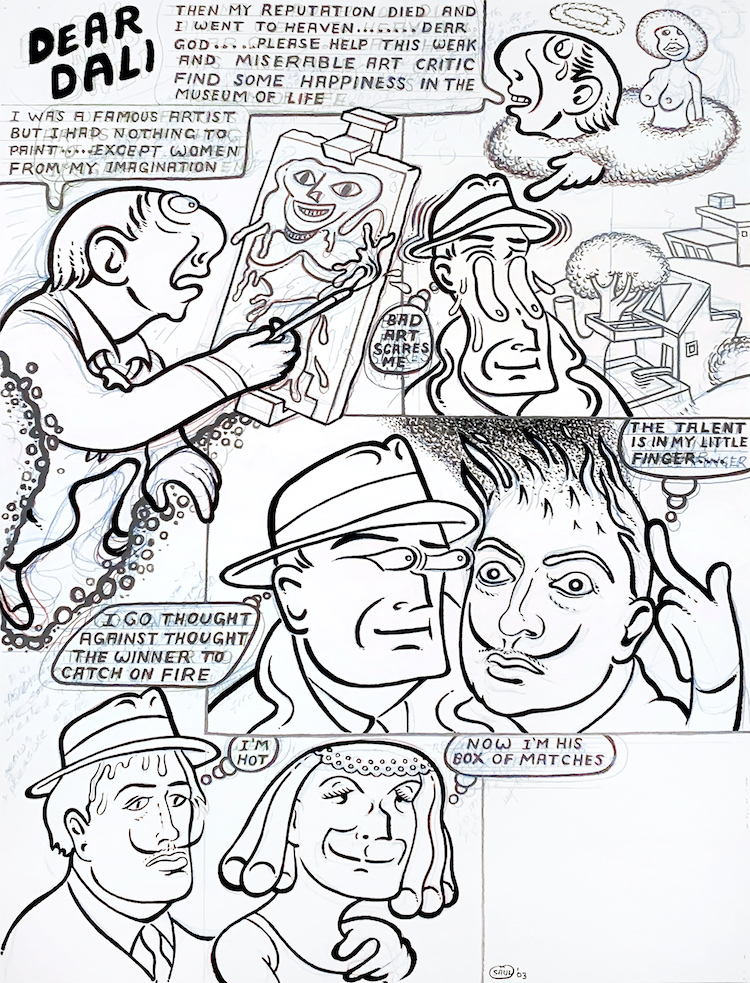

(Peter Saul, Untitled (Dear Dali), 2003, work being auctioned off for the Peter Saul Fund for NYAA)

And Peter, there are just so many more artists and shows and opportunities now. It must seem so different from the era you came out of?

PS: Yes there's many more shows and art now is just so gigantic. I can't even believe it; it's like the third thing happening in Manhattan: you got real estate, finance and art. Bong, bong, bong. And I don't know what happened to law and medicine! I mean as a way to spend time, making art is not like pushing boxes in the hardware store; this is something that is very pleasant.

Anna, what do you think about that? That process and the ritual of making, that it can be pleasant, especially now as you have left school and have a deeper exhibition schedule?

PS: I still have my idea of a work day; 1pm to 7pm approximately.

AP: That’s nice, life goals. That’s the kind of structure I’m looking for. I think it's a privilege that we get to do this every day. I could have never imagined like I could be doing it to sustain myself. Obviously there are days where I'm just like pretty much crying in a corner or just thinking it’s the worst day possible. Then I realize it's probably the best day if

I was comparing it to being back home, you know when I was stuck in suburban Utah. So you have to put it in perspective when you struggle in the studio.

PS: I would think Utah was quite strict, but it must have strengthened you as an artist?

AP: Most definitely I think it definitely made me who I am now. Being in Utah for most of my childhood forced me to quickly adapt and change into different roles, and taught me how to fight against something.

And strict rules make you break rules.

AP: I think that is important. It's what you define it as, right? The environment kind of drives you to challenge yourself and to break these rules or or you set these parameters for yourself to break or stay within. I feel like the medium I chose myself has very strict parameters and I think that's kind of a reflection of life.

PS: I’m glad you paint pictures. We have that in common.Today, art can be anything, I mean you can make a movie of an ice cube melting and it's probably been done 25 times. Art only means man made, so theoretically, according to the language, a salad bowl is just as much art as Rembrandt's Night Watch. I’m not sure why I brought that up but I was thinking about rules.

Why do you think you are both attracted to figurative art?

AP: It was kind of a natural thing for me. My old mentor told me that if I could draw a figure that I could do anything. And being 15 and 16 years old I felt like I should be able to master figure painting or drawing. You know you're constantly interacting with other human beings, and I think it's natural of us to kind of want to depict that and maybe that's also why there's this huge excitement and resurgence for figuration. And that is why I went to the New York Academy of art, because it was touted as such a strong figurative school.

PS: When I started in the 1950s at art school, art was supposed to be figurative, but it was understood that the exciting part of art was Abstract Expressionism. And if you wanted to be part of the future, that was it. So I was just very careful to be rebellious against what was expected of me. I realized right away that you have to be different to be noticed. That is pointless to be a modern artist like every other modern artist. There were too many modern artists, even in 1952 to even remember their names. No kidding!

I think had I been in school a few years earlier, I would definitely have tried harder to be more interesting to look at to counteract Jackson Pollock and de Kooning and Rothko and so on, who weren't all that interesting to look at in my opinion. Mainly, they were really interesting to know about, I mean they got drunk, they did the wrong things, they tormented women, you know all that sort of thing. Oh, they were bad! Okay, okay, right? But their actual artwork wasn't interesting to look at. In my actual opinion, you have to have the human figure, or something with the human form in order to be interesting to look at.

Did you go into art school thinking that you were going to be able to have exhibitions? Was that the ambition?

PS: The ambition was merely to sell art and live through my life without having this affliction of business thrust on me. I was just so happy to be isolated. I was completely anormal; I found a girlfriend who felt the same way I did, and we were just so happy not speaking the language, not talking to anybody, just way out there in a foreign country sitting and drinking beer. Just wonderful.

AP: Sounds like the dream, honestly. I don't know I'm kind of a hermit myself so that sounds amazing. I feel like being an artist you learn day to day how it is to be alone.

Did the last 18 months or so change either of your practices or routines?

AP: Honestly, it was kind of this, the same. Definitely jarring, but I actually kind of liked being undisturbed. Is that bad to say?

PS: I felt the same. I didn't mind the virus on that level either. I mean you worry about getting it, your family getting it and so on, but it didn't bother my work day. I don't think you bothered my wife’s either, we just calmly continued doing what we do.

Peter as we are talking now, you are being honored by the New York Academy of Art this week, Anna’s old school, and I wondered if you either reflect on awards or what it feels like to have this sort of influential recognition in the art world. Do you soak in the adulation at all, or is it back to work?

PS: Really it doesn't soak in because I feel it's not fair that if you don’t pay attention to bad reviews then it's not fair to pay a lot of attention to the ones that are good, you know? You have to sort of keep an arm's distance from all reviews and realize that it's just a changing scene and all objects are basically equal on this level, I mean you know it could be Grandma Moses,

Picasso, de Kooning… anyone could be honored! Boom, suddenly there they there, they are! It could be the worst artist you've ever met, it could be your grandmother, it could be anyone, it could be a teenager! Anybody can be a world famous artist instantly if enough important people think they are.

And that's just the way it is. And if, for some reason, you're flung into this group towards the top, thank your lucky stars, but I never think of it. I try not to think of art appreciation; I think about art, meaning my pictures, and one person standing in front of one of my pictures. And does my picture have a sufficient amount of interest to be looked at. An art collector once told me the average time spent looking at a picture is seven seconds. Maybe it's true? I don't know, but so often I go to an art show and I don't spend long looking at the pictures, then I feel guilty.

Peter I know you were a teacher for years and probably gave great insight and advice to students, but Anna I’m curious what the best advice you received from a professor was?

AP: I think it was to find the right group of peers and friends, the right group of people to talk about your art with. It wasn’t really about art, it was about at the end of the day, it was about the people you surround yourself with. I also think it was the things that the professors told me not to do. I remember one saying, “You just think it’s all going to work out, don’t you?” And I thought, well, yeah! You need to have that kind of like blind optimism and I still have that to this day. I can make paintings and draw everyday and if I work hard enough, hopefully that will be enough. And that optimism is the best to have.

Thank you to the New York Academy of Art for organizing this conversation with Peter Saul and Anna Park // nyaa.edu