As a tattoo and textile artist, Christopher Martin is importantly guided by the tradition of folk art. His reverence for text, appreciation for the history of his material and careful collection of imagery are powerful reminders of how folk and outsider art traditions can be reinvented for new generations, new eras. What speaks to me about Martin’s work is the stark, blunt immediacy that challenges the weight of our world with naked solidarity. On the eve of his solo show at Hashimoto Contemporary in San Francisco, the North Carolina-born, Bay Area-based Martin talks frankly about Southern folk art traditions, race in America and exclusion within the tattoo community.

Evan Pricco: I wanted to start with how and where you collect some of your imagery. There is a historical weight in the imagery, but your remix and reimagining of tapestries, banners, and sewing impart elements of folk traditions. Part of me is wondering about the genesis, but also, about where the research materials come from.

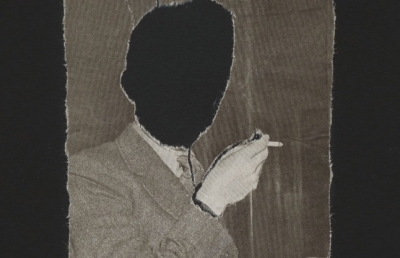

Christopher Martin: Where I’m from, storytelling is a big tradition within the South. I try to capture this folklore through my art and learning more about what inclusivity means in America. By using variations of cotton in my work, both paper and fabric, I’m paying homage to the history that is connected to farming and free labor, which plays deeper into the narrative of my roots while being a free black man today. Also, music is inherently woven into our culture, so I've naturally gravitated to the blues. I love discovering stories through music because the lyrics are anecdotes of slavery and the south.

I think a huge part of 2020 and the reexamination of race came from so many people discovering the nuances of racism. But you were already creating this work, which is not a reaction to 2020; happily, the audience reaction has probably evolved. Can you talk a little bit about that? How have you witnessed the response to your work?

Have you ever read a book or watched a movie from an earlier place in life and have a completely different experience once you revisit it years later? That material never changes, we do.

There's definitely a shift amongst black artists like myself and our audiences—such as gaining a boost of followers on Instagram and brands wanting to collaborate more on “new” initiatives that support diversity and inclusion. Prior to the climate of 2020, I invested time creating and sharing this narrative, so it's hard to decipher if people genuinely appreciate the work I make or are just using me as a tool for validation of their agenda.

I've always had this really deep love for textile art, but to be honest, it's definitely a tradition that I've had to really, really try and study. There are always amazing stories of textiles within Outsider Art, and then you have someone like Bisa Butler who is actually re-inventing quilts and their inherent stories. Where and when did you start to feel excited about the possibilities of textiles and sewing as part of your practice?

I was interested in making sustainable clothing for myself when I was in high school, and that later expanded into a homegrown brand with my Mom. I gained confidence in textiles when she gifted me my first sewing machine and taught me the basics. Before moving to California, I took the old tablecloth fabrics that were just sitting in my parents’ basement. They were a perfect size, but I didn’t know what I was going to do with them.

One of my first banners was an image of a ball and chain for a group show called Black Mail in San Francisco. Prior to that, I never had any experience on how to actually make banners—it was instinctive, and I really enjoy the idea of layering fabric to tell a story.

My banners were hitting different than my prints for a few reasons: the storage was easier to maintain because I could roll them up, the banners naturally gained more attention because of their size, plus I really enjoy seeing my work on a larger scale.

And a simple question, why black and white?

I love the simplicity because it's the strongest contrast while being easy on the eyes as it plays into the clash between black and white people in America. I also appreciate a strong design that is bold and graphic without any distracting colors.

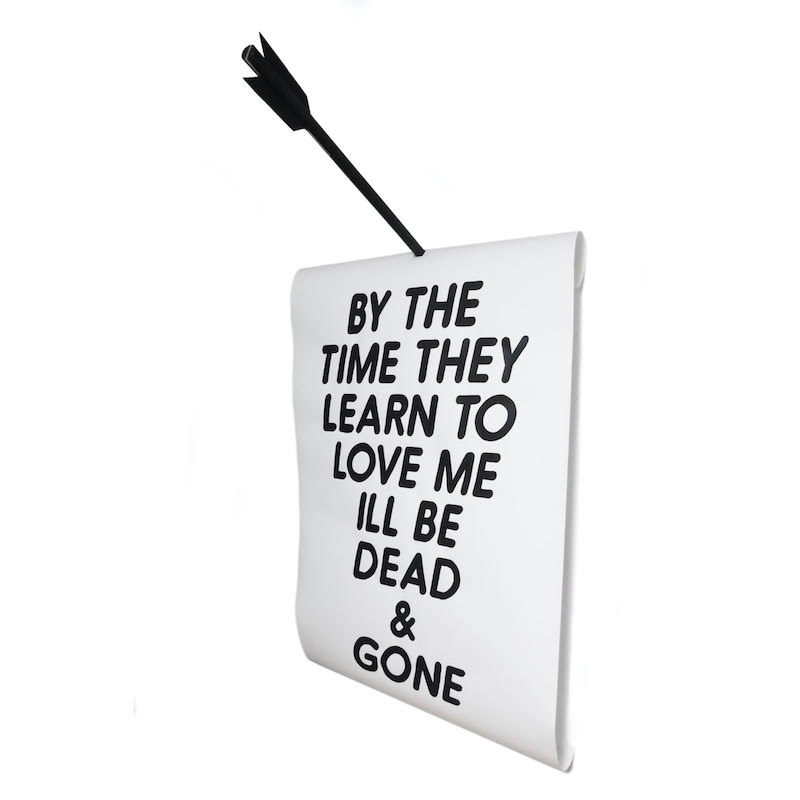

Where do these lines come from in the text-based work?

Initially, it was from blues songs and documentaries, but it's evolving into everyday conversations that I hear. I’m starting to reference lines from hip hop songs these days. They still have that same oppressive feel as the blues, but more gritty and unapologetic.

What is so incredible about the text work is how naked it is, if that makes sense? Like these powerful words left to just be the whole art piece. It's so damn effective. Did it take you time to realize that the words were the art? Did you feel vulnerable leaving them alone?

I archive interesting quotes and phrases from conversations, books, music, etc. I usually write them down, never having any intention for them in my work. Back in 2019, my friend asked me to partake in a duo art show titled Love Letters From a Runaway Slave—this was the perfect time to use these phrases I had collected and curate them.

We can't take for granted the power that words yield. For example, we’ve seen the media twist headlines over and over again in ways that can be hurtful to our community. There is definitely an art to communication, and sometimes you just gotta tell it like it is like, “Here, let me actually spell this out for you.”

There’s always a healing aspect when putting out a piece of art because a lot of me is so invested. But I think there is something special with an element of text because there’s another level of vulnerability. The messages change depending on the theme and context of the show I’m in. Every viewer has a different take-away from the quotes based on their life experience.

We can't go through an interview without talking about life over the past 12 months. For many artists, hunkering down and working is their ideal life to begin with. But everyone is different, and America has gone through so many "lives" this year. How was it for you?

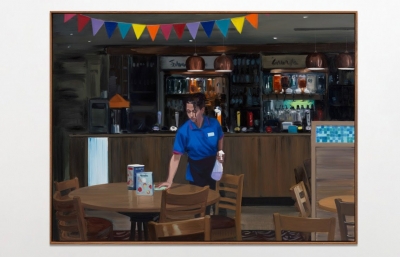

With all of the calamities in the year, I was confronted with racial bullshit within the tattoo community. I left the last tattoo shop that I worked at because of a racially charged incident that originally started off problematic for other reasons. The challenges black people face in business are not unlike the problems we face in the world, period, which largely involves the constant fight for respect and equality across the board.

I feel blessed to now work at Tres Leches Studio, a community of like-minded creatives in the tattoo industry. There’s an invaluable peace of mind working in a QTBIPOC space. This industry has proven time after time, that white folks in particular have invoked a lot of trauma. It’s important to detach yourself to heal and focus on your own personal growth.

Black liberation has nothing to do with equality. I’m not interested in being equal with the oppressor. We need to create, build and nurture our own structures and radicalize the notion of for us, by us. The revolution starts with self, what we practice and consume and how we take care of ourselves.

For the solo show at Hashimoto this spring, is this what you are working on? These conversations and dynamics?

I've been building a large body of work based on African American traditional tattoo imagery for a while now with banners and flash paintings. The work for this show focuses on sailor tattoos by referencing traditional flash, dissecting it, and inserting black culture.

Christopher Martin’s solo show at Hashimoto Contemporary in San Francisco will be on view from March 6—27, 2021 // This article was originally published in the Spring 2021 Quarterly edition // Portraits by Shaun Roberts for Hashimoto