It doesn’t get much more Americana than taking off on a motorcycle on the open road with only the vaguest idea of a destination, and even less of a notion of who and what you might encounter along the way. It’s today’s version of riding off into the sunset on your horse.

But venturing out towards the horizon isn’t only an American fascination, it’s intrinsic to us as humans. We want to know more, explore and find out why we are here and what else is out there. As Todd Blubaugh so effectively communicates in the story of his journey across the country, it’s vital for us to remain in motion, whether physically, emotionally, or spiritually. The motorcycle is his vehicle of choice, but, as Todd explains, “the bigger point is movement and what we learn during our displacement.”

In 2013, one week before Todd was scheduled to leave on a motorbike trip across the country, both parents were killed in an automobile accident in Kansas. After flying back to Seattle from the funeral, Todd remembers, “staggering in an emotional tempest, I packed my bike with tools and camera gear and left.” The photographic and written account of his encounters along the way are documented in his new book, Too Far Gone. “Traveling by motorbike can be a deeply spiritual experience,” Todd relates, “There are no distractions—the only conversation to be shared is between you and the highway. Incidentally, we had a lot to talk about.” —Alex Nicholson

Alex Nicholson: When did you first starting taking photos?

Todd Blubaugh: My mom, who was an artist, introduced me to my first camera in junior high and by high school, I was hooked. It just made a lot of sense after that.

How about your first bike?

My dad made me a deal, he would let me have one if I agreed to mow some lawns in the neighborhood. He got a little Kawasaki KE100 from a friend of his and that was all it took. I could get around anywhere I wanted to, I explored all the county roads behind the house. Me and my friends at that point were pretty unstoppable. Your first step of independence is a powerful little pill.

As someone who studied visual arts in college, was that something you always wanted to pursue?

I started in film then changed to photography, then illustration and design. My degree went all over the place until I graduated in something called visual concepts, which was a lot of everything.

That helped you get the job in Seattle?

Yeah, it did. Right after school, I applied for a job at a company I really wanted to be a part of because they specialized in outdoor sports. I did that for almost seven years. I ended up doing more studio photography than anything in that job. I never really got to be in the field as much as I wanted. As a creative, you rarely get to do the things you want, as the process demands you to compromise.

Tell me about connecting with the folks at the Twinline Motorcycle shop.

I lived in this neighborhood where there was a bike shop, and I became good friends with guys there. We actually moved the shop once I became a part of it, and I eventually transitioned my studio into it. I was able to bridge the two aspects of my life that I really loved: photography and motorcycles. It was a really great group of people that came together under the passion of riding bikes. Whenever you get deeper into the culture, it takes a tremendous amount of time and tools and you have to have an adequate facility. That's all the bikes do; they destroy themselves as you ride them. That’s the nature of the relationship. It requires maintenance.

Do people gravitate towards those places because they're all looking for similar, bike-minded people or come from places that didn’t have it?

Yes, it attracts the bike-curious. There's something pretty powerful when you share a passion, no matter what it is. People will gather. The thing about motorbikes is they give back as much as they take from you; it’s an even exchange. Those not willing to put in the time will always be kicking tires, but those willing will appreciate every mile. There's a celebration every time you ride a bike, especially with friends.

It must be similar to that initial feeling of independence when you took off with your friends on your first motorbike. Is it the same every time you go for a ride?

Absolutely. You just don't want the party to stop; it feels so good. Then you start making changes in your life and making your bigger picture decisions around being able to continue riding bikes with people that you love riding bikes with. It's perpetual. It’s what led me to live in a warehouse with all my friends and all of my tools. Every decision I've made since then has somehow been formulated around keeping my tires turning.

Your life has also been shaped by a very tragic event. After your parents passed away, you packed up and took off on a motorcycle journey across the country.

Yes. A whirlwind of circumstances led to that journey.

Is there an experience on the trip that you can single out as a significant moment?

Arriving home was a big one. I was nearing Kansas after riding through the whole west half of the country. A big part of this journey that I wanted to do for the book originally involved my parents and going to see them along the way. I hadn't been home for summer in twelve years, and they were very excited. So when I did come home, it was just so different. It was so empty and vast in that part of the state, just two horizons.

Riding through, I had a mechanical breakdown. A battery fried on me pretty much out in the middle of nowhere. I was just forced to sit there and address this problem, and it all kind of became beautiful again to me. That was one moment that I remember specifically, realizing I used to hate the place and the nothingness of it. I started to like it again, returning. It's bittersweet.

Although motorcycles are visually the center of the book, we discussed how they are simply a vehicle for your journey, which is the focus.

The book has very little to do with motorcycles, more so to do with what you find along the way. They are just the vehicle I enjoy because they challenge me. They supply you with a lot relative insight, but you can get that from anything that moves you, bicycle, car, boat, whatever. The bigger point is movement and what we learn during our displacement. Whatever you want to challenge yourself with is the bigger picture. I tried not to focus on the bikes and make it more about the people along the way.

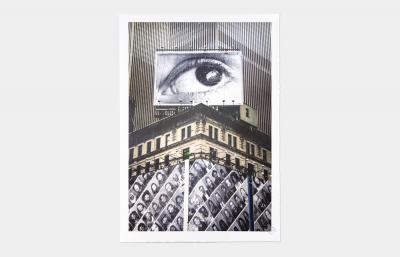

I love the spreads in the book with all the faces of people you met.

I’m glad. This story is basically a big thank you letter back to all of those faces. I owe it to them. They were there for me when I needed them most.

If you stay in one place, the spectrum of people you meet shrinks.

Yeah, definitely. I think the variety that you encounter geographically teaches you a lot. One, about tolerance and understanding, and two, that you can’t write off the similarities or the things you do share in common with these people that you never thought you did.

Despite there being so much more information available to us these days, it’s still so easy to get stuck seeing only what we know, and now, with what Google and Facebook thinks we want to see.

It’s very easy to write off a different perspective, politically and culturally, until you go visit and understand the human undercurrent there. You have to move about to get to the core of people. As much as you read, or look to the news to fill this curiosity, you're always going to come up short until you have that conversation face to face. I’m not saying you have to move about perpetually, but making yourself move and visit these different places really gives you an appreciation for diversity. And you're not only creating an understanding and tolerance for someone else's culture or differences, you're also introducing your own to them by just simply being there. By reaching out, you start the process of breaking down some of the misunderstandings that exist.

That probably summarizes the world’s biggest problems, misunderstanding and lack of communication.

That’s so true. So pick a vehicle, go out there, and break down the walls.

Friendship, and the people you met along the way, are a big part of the book. Can you explain the difference between riding in a group, riding with a buddy, and riding solo? How did each affect you creatively?

Riding with a big group is sort of this party experience, but not every party is a good party. When you’re riding by yourself, there is no hierarchy, there is no struggle for direction, it’s just wherever you want to go. That is really special and fun, but you don’t have anyone to share experiences with. Those miles that you share with good people, they really add up to strong memories.

I had a much easier time writing things down and thinking about life, the journey, both physically and mentally, when I was by myself. My thoughts were a lot more clear. So if that’s what you’re seeking, go out alone. The creative process is definitely better in isolation. But in terms of the journey, you are robbing yourself of a broader experience. The shared experience is more powerful. It lives longer too. You have someone to reflect and review it with. And those are amazing conversations you’ll have the rest of your life. They kind of extinguish themselves when you're by yourself. It’s not the same.

A part of your trip that stood out to me was the encounter with the old sailor in Sausalito, perhaps because my father lived on a boat there at one point.

That was just the moment I realized that I didn't need to be out any longer. I saw the writing on the wall after talking to that old fisherman. I didn't want to become any more detached than I already had in the six months I spent out riding around.

There must be some serious comparisons there with sailing and the feeling of being on a bike. Both require movement but being in solitude.

Yeah, I hear a lot of people talk the same way about it. The sailor recited to me what was already going through my head within moments of talking to him. There was this question he asked me that threw me off so quickly. I saw him walk up and check out my bike and sit down next to it, just kind of staring at it. I was expecting him to ask me something, but the question that he asked was so well placed. He didn't ask anything about the bike, he didn't ask anything about me building it or where I was from. He simply said, “How long have you been traveling? How long have you been at it?” That's what he said. I was like, "Oh my God, I guess it's been six months." I had to calculate it. “You’re at the crossroads then,” he said. He followed that up by telling me that was about as much time as it takes to become detached from everything. He had begun taking his boat on longer and longer trips. On one of the trips, after about six months he just decided to keep going. He'd been living on the boat for over forty years and had circumnavigated the globe several times. He told me he might go to Thailand, get married and have some Thai woman take care of him when he was too old to sail anymore. I thought, I don't want to do that. I don't want to go that far with it.

What did you learn about yourself on the trip, things you came to understand that you hadn’t before?

Oh yeah, man. Of course, I always leave room to be wrong, just as a disclaimer. I figured some things out about myself in particular and about people, and I guess the human condition. A big one was something Ethan, who accompanied me on much of the trip, and I discussed regularly: how important it is to stay in motion. Things that stay in motion really do have an interesting, kinetic life. He chose to stay in Kansas because he met Ariele, but his momentum was the only reason their two separate paths ever crossed in the first place. After that it made more sense for them to move forward together. They're still making progress. It just changed, it changed from the highway and the miles we were putting down to an emotional momentum between the two of them. It was beautiful to observe.

Taking all that into consideration, ultimately, any time we as humans become static, we die, or feel like we're dying. There are so many things in our own biology that have to keep moving to keep us alive. We should always strive to be moving in some capacity. So, there's that.

Friendship, movement, solitude, these all seem to be big themes in our conversations.

Yeah, and I realize the conversation isn’t for everyone but I think the photos alone are enough of a story for those uninterested in open ended metaphysical conversation. I just hope it inspires people to get busy and get after the things they really want in life.

You are inspiring me to want to go on adventure of my own. I just need to figure out what my “motorcycle” is first.

Perhaps it’s actually a motorcycle. I think you would really enjoy it.

Don’t tell my mom. Even before the journey, publishing a book has always been one of your goals, so how does it feel now that it’s finally happening?

Terrifying. It’s a goal for every photographer to publish their work in once place but once you get that far it’s actually pretty fucking scary to let it go. I just want to thank Belle & Wissell for giving me the opportunity.

The book contains several letters you wrote to people along the way, but which you have yet to deliver. What made you decide to start writing those and when do you intend on sending them?

I found a letter from my father, which is the final closing story in the book. My dad wrote me a letter and left it in the attic among his personal possessions where he knew I would be looking if something ever happened to him. It was a very calculated and intuitive measure that he took. It was very thoughtful and I don’t how to explain how powerful it is to hear someone’s voice after you have a comprehensive understanding of their life. When you have a limited understanding of someone’s journey in life you don’t necessarily feel the impact of the entire weight of their existence being put into this one document. When you can understand the whole story and then can revisit those words, they are far more powerful. I think being revisited by something when you can understand it comprehensively is much more effective than just taking little bites, and I understand that because of the letter my father left, and I'm trying to, in some way, emulate that with the book. To me, this journey isn’t over until I deliver those books to those people. And unfortunately, there were many that didn’t make it into the book. Someday I would like to deliver those letters too. This journey will be done when it’s done and those people have what I intended to give them. Which is a “Thank You.”

Too Far Gone is published by Gingko Press in association with Belle & Wissell Editions. Visit gingkopress.com or visit your local bookstore to purchase a copy.

----

Originally published in the July, 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, on newsstands worldwide and in our web store.