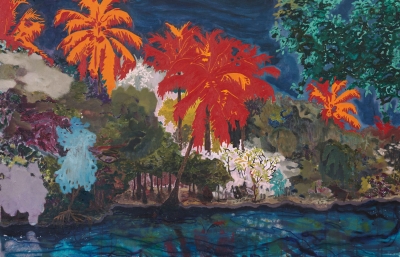

It’s easy to get lost in one of Robert Burden’s paintings, and that’s the idea. He invested the time, and so should you. Beginning his under-paintings with bright blue, which he chooses for the rich value range that supports the strong colors pulsating his universe, he creates grand epics. Currently working on Battle for the Arctic, which features Vladimir Putin and Prince Haakon of Norway, as well as Hermey the Elf from Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, he invokes the innocence of youth to explore huge themes. The first big one was The 20th Century Space Opera, his ode to Star Wars.

Read the full interview in the August, 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine.

Gwynned Vitello: No one starts off a music career composing an aria, so let’s start at the beginning, which I imagine was you playing with toy figures.

Robert Xavier Burden: Animal figures, especially gorillas.

Were TV shows and movies your first inspiration, or the toys?

Like a lot of artists, toys were probably some of the first things I ever drew. So I'm not entirely sure which came first or which mattered more.

Were they all lined up on a shelf in your room in a certain order, and was there a favorite series you collected first?

My cousin’s Star Wars toys are the first action figures I remember playing with, and Battle Cat from He-Man was the first figure I remember having, but Batman, Ninja Turtles and anything related to King Kong were big for me. I would set them up for drawings, not really on a shelf.

Am I wrong in guessing that you particularly liked history, English or maybe math, given the precision of your compositions?

I think the precision has more to do with being obsessive than being a math whiz. I always enjoyed history and English, especially writing classes.

How did you choose an art school, and what was your first focus?

I was raised in a pragmatic, sports-centric family. My dad was a very good hockey player and he tried his best to turn me into one as well. For the first 16 years of my life, all I did was go to school, play hockey, and draw whenever I had spare time. But in high school, I pretty much had a breakdown. I hated the game and it was a miserable time in my life. I told my dad that I was going to try and pursue art instead. I love the man, but that was a tough conversation. We didn't really talk for a while afterwards. I think I chose an undergrad program at a school that offered a broader education beyond just studio art because it left the door open for something like law or business school, which would have made the family pretty happy. But I was accepted to the MFA program at the San Francisco Art Institute and decided to take a chance and make the move to San Francisco. Given the kind of work I wanted to make, California felt like the right place to be.

What was your approach to becoming an art professional, and what was the first painting you made with an intention to sell?

One of the most difficult things about this body of work is that it almost goes out of its way to not be commercial. The work might be provincial in content, but it's an inherently elitist luxury item. It's not like film, music, or writing, which are supported by a mass audience and can garner royalties. My career is at the mercy of very rich people. It doesn't do me much good if 10,000 people like my paintings. I need one very rich person to love my paintings, enough to pay a small fortune for them. This is obviously a huge problem for me, and because of this, I don't really consider my work to be commercial at all. I've been told my paintings are way too conceptual and expensive for the fan art world, way too large for most commercial galleries, way too slow for social media culture, but way too nerdy and fanboy for the high brow scene. Sticking to the vision of the work has placed me in this weird no man's land, and I have paid a personal price. I'm in my mid-thirties and don't have a family, don't take weekends off. I live in a warehouse in one of the only affordable pockets of SF. I don't ever want to sound like I'm complaining. It's a privilege to be an artist, and I've been very fortunate to keep my practice going. I occasionally sell originals. I'm part-time faculty at a couple different colleges in SF, and I have a small but awesome fanbase that has been tremendously supportive through the years.

How do you go about planning a painting, how much planning ahead?

I plan ahead quite a bit. Some of the paintings in the studio right now are paintings that I’m currently thinking about, and if I’m lucky, I’ll get to them in a few years. When I started this body of work, I was just depicting a big toy on a big canvas with a wallpaper, rug or fabric pattern from my childhood home. But as the ambition of the work has grown, the compositions have become more complex, using patterns from around the world, like Gothic stained glass, French tapestry, Persian and Moroccan rugs, and Eastern mandalas, as well as some patterning that I’ve just made up. These decorative motifs have become a compositional vehicle for displaying many different figures. This is the most laborious part of the process.

Let’s find out how the Star Wars piece came about; the details about its size, how long it took to do, and all that.

I did a Kickstarter in 2013 to help raise money to make three enormous paintings, and the Space Opera (Star Wars) piece was the first of the three to be completed. That was an interesting experience, as the project I proposed was way too ambitious for the amount of money I was asking; but the support of my backers was really inspiring and I wanted to thank them by trying to make the most ambitious Star Wars oil painting ever. I wanted it to be a history of Star Wars and the toys. It's 15 feet by 8 feet and took roughly 2000 hours of studio time spread out over 18 months. It depicts about 165 different Star Wars toys, mostly from the original trilogy. I have a friend in LA who sells vintage toys. I gave him a small painting of Greedo, and in return, he gave me most of the figures in the painting. A lot of people love it, and a lot of people really don't. I think when it comes to Star Wars art, the average fan has come to expect a certain aesthetic—something that looks like a Drew Struzan poster, or something that's easily accessible online, or just a realistic drawing of Yoda copied from a photo. Don't get me wrong, I adore a lot of commercial illustration, but that's not my background and this isn't meant to be a poster or on the cover of a DVD. It's meant to be seen in person, like a museum piece, and that can come across pretentious, peculiar or even irritating to some Star Wars fans.

What was J.J. Abrams’s reaction to seeing it, and have you met any other operatives connected to the movie?

He had some questions, mostly about style and aesthetics, and I think he liked it. A couple Lucasfilm people have seen it, and some folks suggest I get George Lucas to buy it—as though I could just call and invite him to my Hunters Point studio to check out the painting and have a couple beers with me!

Who are your favorite characters and film heroes or anti-heroes?

I always loved Lando. But about a year ago, I met Jeremy Bulloch, the actor who played Boba Fett, and talked to him and his wife for a while about the painting. They're two of the most genuinely kind people I've ever met, so Boba Fett's my answer. Outside of Star Wars? Indiana Jones. SpiderMan, Rick Blaine, Andy Dufresne, Quint, Hooper and Brody—and Batman.

When did you first attend Comic-Con, and what does it mean for you?

I attended it as a visitor back in 2012. A friend gave me a pass so I flew down. It was a crazy spectacle and I loved it. I applied to be an exhibitor, and though I only got a few weeks notice, they gave me a large booth and a discount! People don't go there looking to drop tons of money on art, and some people are genuinely confused by my booth. A couple walked by that first year and said, “That's a really cool banner.” I was like, “Thanks. It's a painting that took a year of my life.” But I have a blast being there.

What is your favorite part about going?

It's a very positive atmosphere. There are so many talented people walking the floor and exhibiting, and most everybody is just really excited to be there, finding joy in their surroundings. You'd think it might be this really competitive and cynical environment, but I haven't found that to be the case at all.

After attending such a huge arena show, what’s it like coming back to your studio?

Peaceful.

Do you basically work alone?

Yes. I don't have studio assistants or anything like that, and you obviously have to be good at being alone if you're going to make work like this. Space Opera took about 2000 hours, and Flight, which will be complete by the time you print this, will have taken me roughly 2700 hours. But, to be honest, these paintings test your patience and the ability to handle solitude.

Who influences you?

Some of my favorite artists—William Kentridge, Todd Schorr, Walton Ford, Drew Struzan, Dan Lydersen, Henry Wyndham Phillips, Anselm Kiefer, Botticelli, Joseph Cornell—are people that have influenced my work in some small way. There are a lot of textile designers from the nineteenth century that are clear stylistic influences. Every once in a while, a critic says I'm a Kehinde Wiley or Jeff Koons rip-off, which is bizarre and ironic, and a little disheartening. I like those artists but don't think I have much in common with either. Maybe some tenuous conceptual similarities with Koons? Wiley and I both make big paintings with patterns, something that artists have been doing for hundreds of years, but our motivations and subject matter are entirely different. Imitation and influence are very different things. Stylistically, Banksy looks like Blek le Rat, but that doesn't mean Banksy isn't a great artist.

Your YouTube videos are accompanied by a wonderful variety of music. How involved do you get with the soundtracks, and how important is music to you?

Music is probably the highest art form. But I'm not a musical person. I've never had the desire to pick up an instrument the way that I needed to pick up a pencil or a paint brush. I have some musician friends that did the music, and they did a wonderful job.

I love the framing of your pieces. When do you envision them in the process?

Thanks! I used to frame everything because it was a way of displaying the toy with the painting. They were acting as a sort of modern altarpiece or reliquary for these objects, so it made sense. I also enjoyed making alterations to the frames, adding ornamentation by making little figures that I cast from silicone molds. But framing doesn't feel necessary anymore. The Holy Batman, Battle Cat and Optimus Prime needed those frames, and were part of the plan from inception. But I don't think Space Opera or Flight need frames.

Having made a conscious choice to focus on a genre, and committing to spending so much time on one piece, do you question such a decision?

Every day. It's very difficult to build up momentum in your career when you make such labor-intensive and massive work. Labor is a huge risk, especially when dealing with subject matter that doesn't have universal appeal like portraits of beautiful women, landscapes or animals. Labor doesn’t automatically equal great art, but in the contemporary art market, it doesn't have much value. A painting that took 3 hours might be deemed more valuable than a painting that took 3000, and they're both just as easy to dismiss. So unless it's a commission, you really have to believe in what you're making if you're going to spend so much time; otherwise the risk of labor can eat you up inside, and can make you desperate, which begets resentment and bitterness. You end up playing chicken with your life a little bit, and that can be scary. But you can't have everything, and you have to make choices. I've painted about 3000 hours every year for the past decade. I'm a much better painter now than I was 3 years ago, let alone 10 years ago when I began this body of work. So I'm excited about where the work is headed and I've got many more epic, toy-themed pieces that I'd like to make before I move on to other kinds of paintings.

Do you rely on commissions from fanboys and girls in order to just do what you really want?

I don't take them on often, unless they sound interesting or I want to do someone a favor. A few years ago this guy commissioned me to make a giant painting of Bumblebee from Transformers as a surprise birthday present for his girlfriend. That was a fun project.

Do you worry about creating such dense art for an audience that increasingly has a shorter attention span?

Definitely, especially when I could make a digital image of something similar in a small fraction of the time. Pictures have never been so ubiquitous and almost meaningless. We see thousands of images everyday. Making a painting that somebody will want to stare at for more than 10 seconds is a huge challenge, but I'd like to think that if you see my paintings in person, they just might accomplish that.

Robert Burden will have work on view at Gregorio Escalante Gallery later this year. He will also be doing live painting on this 12ft 'Dinosaur' piece in booth #4315 during San Diego Comic Con (July 20-24).

----

Originally published in the August, 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, on newsstands worldwide and in our webstore.